Ordinary Tunisians are volunteering to help sub-Saharan African residents who are being persecuted. They say the issues behind the current crisis — racism and migration — should have been tackled long ago.

In a cobbled lane in the Tunisian capital, canvas has been fixed to the white walls of a nearby garden to form shelters. Here and there, you also see actual tents, draped with tarpaulins and blankets to keep the rain and cold out. The sky is overcast today, and people are sitting around open fires to keep warm. Piles of garbage flank the small, central city encampment.

It is a messy scene, but Josephus, one of around a hundred sub-Saharan Africans who have been forced out of their Tunisian homes over the past fortnight, wants to show DW where he, his wife and child are now living: in the street, right outside the headquarters of the International Organization for Migration, or IOM, a United Nations agency, in Tunis.

Using the camera on his phone, Josephus has been touring the lane. These fires also serve as guard posts at night, he explained as he live-streamed the scene, because that is the time the people here most fear that groups of Tunisians will come and try to attack them again.

All of the people now staying here arrived over the past two weeks, following an inflammatory speech made by Tunisian President Kais Saied. Faced with mounting economic woes and ongoing political turmoil, the increasingly autocratic Tunisian leader appeared to resort to racist, populist tropes to target sub-Saharan minorities in the country.

In official statements, Saied implied that “criminal” sub-Saharan Africans with “no affiliation to the Arab and Islamic nations” were part of a conspiracy to replace the local Tunisian population. He then ordered local security forces to expel illegal migrants who had come from the sub-Saharan region.

Diplomatic problems

The African Union called Saied’s speech “racialized hate speech” and postponed a conference due to take place in Tunisia in March. On Monday evening, news agency Reuters reported that the World Bank was pausing its work with Tunisia because of concerns about “racist violence.”

Since giving the original speech, the Tunisian president has softened his stand somewhat, saying racist attacks would be prosecuted. But his backpedaling, which did not include an outright apology, doesn’t seem to have staunched the racist attacks.

According to local rights groups, there are anywhere between 21,000 and 50,000 sub-Saharan Africans living in Tunisia. Some are there legally as students; others are undocumented workers who have arrived thanks to Tunisia’s three-month visa-free entry laws.

But legal status didn’t seem to matter after Saied’s speech. Black people, and even some darker-skinned, native Tunisians, were harassed on the streets, arbitrarily arrested, beaten or otherwise attacked, thrown out of rented accommodation and let go from their jobs. On social media there were stories of people being denied service at post offices or stores simply because of skin color. Tunisian police have reportedly been slow to respond to crimes reported by sub-Saharan Africans, and taxi drivers have refused to pick them up.

As a result of the persecution, hundreds of Africans from sub-Saharan regions have since returned home on government-organized repatriation flights, including to Mali and Ivory Coast.

Others, like Josephus, have no choice but to stay. Originally from Sierra Leone, he has been working in Tunisia since 2021 and trying to have his asylum application processed in Tunis, so far without success.

“We are around 90 people here,” he continued. “Mostly people from Sierra Leone but also Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Ghana, Liberia, Senegal, Cameroon. It’s the only place we feel safe.”

Local volunteer networks

Josephus approaches a young Tunisian woman who just arrived in the lane. “I think you should speak to her,” he says. “The lady you are seeing, she is Tunisian, and she is helping us because she does not support what her government is doing. Sometimes she takes our phones and charges them for us.”

“There’s a group of about 50 Tunisians who are helping,” the woman, who wants to be identified only as Amal, told DW, after Josephus handed her his phone. “The majority of us are human rights activists in Tunisia but right now we’re trying to find a solution, just as citizens.”

There is also another similar camp of displaced sub-Saharan Africans in the city, Amal explained. The Tunisian volunteers bring material for tents, food and diapers for the children to both.

Besides helping with supplies, the Tunisian volunteers have undertaken various other tasks to help the displaced people, too. Some are mediating between Tunisian landlords and sub-Saharan African tenants, trying to convince the landlords to let them stay. Others are delivering groceries to families who are too afraid to leave their homes for fear of being attacked, and they have set up donations pages to collect funds for this. Members of the Tunisian organization of young doctors has been coming to the camps in the evenings to check if anybody needs medical treatment.

“It’s like we’re trying to learn how to live in the middle of a war,” Amal says, sighing.

Henda Chennaoui, one of the coordinators of a newly formed organization, the Tunisian Anti-Fascist Front, which consists of civil society groups and human rights activists, told DW she knows of about 30 different local and international organizations trying to help the stranded sub-Saharan Africans at the moment. Some of these have provided accommodation for mothers and children. Private citizens have, too, she added.

“I can’t give any details because the police are also persecuting activists and volunteers who are helping,” Chennaoui added, referring to recent wave of apparently politically motivated arrests of opposition figures by Saied.

On Saturday, the Tunisian Anti-Fascist Front was one of the groups behind a march against racism with the slogan, “Abolish Fascism, Tunisia is an African Land,” that was attended by hundreds in Tunis. Tunisia’s large and influential General Labor Union organized its own, larger march against Saied on Saturday, too, and also displayed anti-racism posters.

Both Chennaoui and Amal believe that there’s a lot more at stake than just what’s happening in their own country at the moment.

“We [Tunisians] know that we are stopping immigration from Africa into Europe and that this is a big political issue,” Amal complained, arguing that it was also about the issue of migration in general. “Our president was stupid enough to make a racist and fascist statement — but the issue is actually bigger than that.”

Addressing racism in the region

The signs of this crisis were there long ago, Chennaoui said. People here tend to think racism is about white people discriminating against Black people, she noted. “But maybe it’s time to face the reality and say that there is racism in Arab countries as well.”

“When you say something that violent in a society that is already racist, it’s playing with fire,” Salsabil Chellali, who researches Tunisia at Human Rights Watch, told The New York Times.

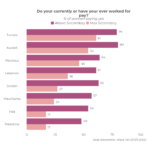

Those comments jibe with the results of last year’s report from the Arab Barometer organization, which found a worrying gap between perception and behavior toward Black people in the Middle East. A majority of 23,000 people surveyed in 10 countries in the region all thought racism was a bad thing. But far fewer of them believed that discrimination against Black locals was a problem.

For example, although close to 70% of Iraqis say they think racism is bad, only 31% believe anti-Black racism is a problem in their country. Black Iraqi activists vehemently disagree.

Read full article at DW