Since 2023, Egypt has re-established institutional relations with civil society, both to regain trust at home and to prove to the international community that it has endeavored to moderate its political approach after years of repressive policies that have paralyzed the fabric of society. However, this political decision was taken against the backdrop of an economic crisis that continues to expose Egypt to structural and political risks of instability, mainly due to foreign debt. In 2019, the government issued Law No. 149, which revises the regulations for domestic and international NGOs operating on Egyptian territory. The discourse on NGOs and ENGOs between 2014 and 2018 has enabled the construction of political narratives about threats to national security; and in this framework, Law No. 70 of 2017 found its legitimization in what became a “dispositif of repression”. The revision of the NGO law must be seen as the result of the state’s attempt to further compromise (i) domestic demands for a renewed openness to citizen participation and NGOs, and (ii) as a state strategy to strengthen relations between institutions and the youth as the “new” selected- constituency. A first dialogue between youth and institutions dates back to 2016, when Egypt launched the National Youth Dialogue with the aim of celebrating patriotism and civilization and strengthening the role of youth in the country. It is within this framework that Law No. 149 and the environmental approach it enshrines should be seen. Indeed, while Law 149 introduces some penal alleviations compared to Law 70 of 2017 and promotes a favorable civil society, it paves the way for a multi-layered centralization of state apparatuses.

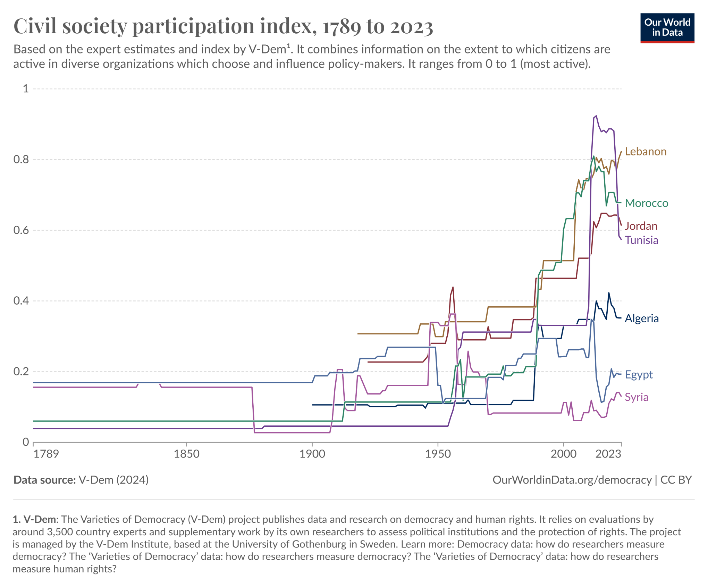

The law legalizes new NGOs exclusively under the premise of “ecological and social development”. This is in line with the overall prioritization of the development and industrialization agenda, which has revived Egypt’s economic and regional ambitions since 2019 as part of the Social Development Goals and the Egypt 2030 vision. Against the backdrop of environmental degradation, the “Youth Loves Egypt” foundation, which was established back in 2012 during Egypt’s political transition, has taken on a new role in the country and institutionalized itself. It was placed under the umbrella of the “Haya Karima Foundation”, which was established in 2016 and revitalized by Presidential Decision No. 202 of 2019 and is active in the fields of environmental protection, social solidarity, development and health services. However, analysis of independent data from the V-Dem project shows a clear difference in civil society participation and size between Egypt and the rest of the Middle East by 2023, with independent data showing that the number of civil society organizations in Egypt is shrinking despite legislative changes (Fig. 1). Moreover, the V-Dem data shows that the degree of autonomy of civil society organizations, i.e. the ability of the state and citizens to freely and actively pursue their political and civic goals, is bound to decline in Egypt as the year progresses and decreased significantly between 2022 and 2024, following the reforms enacted to reshape civic participation.

Fig. 1. Civil Society Organization in Egypt, 2019-2023. Source: V-Dem Project, 2023

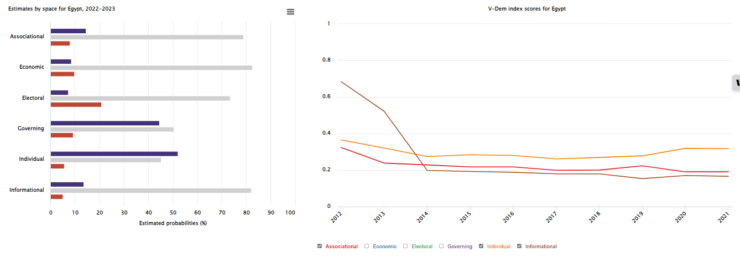

However, the organizational capacities of civil society organizations have improved since 2021, indicating that forms of structural restructuring are being implemented in the country. The constraints still faced by civil society organizations in Egypt are more related to access to funding, with the freedom or difficulty for NGOs to receive foreign funding playing a role, as the following data shows (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Data on NGOs’ capacity in accessing international funding. Source: V-Dem, 2023

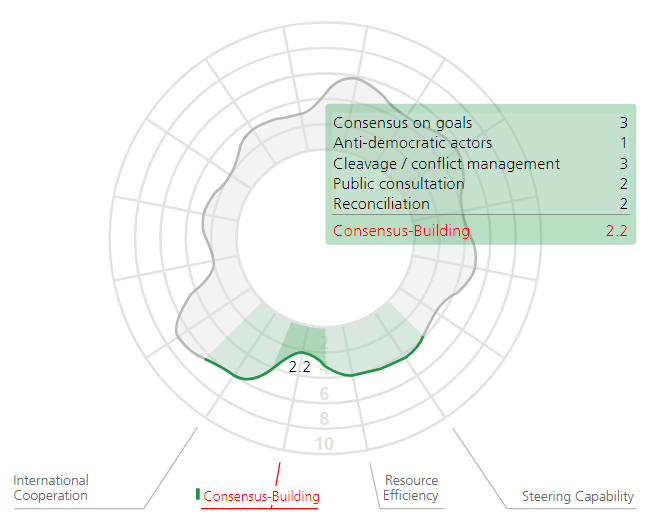

There is a purely structural-political explanation for this discrepancy. Material resources and thus access to funds are the basis for processes of structured anti-state mobilization. The more the organization can rely on material resources, the more the network strengthens its ability to organize actions and social activities that polarize the domestic political arena. For decades, this logic was applied to political parties when party politics was institutionalized in the early 2000s, resulting in the Muslim Brotherhood being better organized in contrast to leftist/secular parties and movements. The same reasoning applies to NGOs in a context where political consensus is declining vis-à-vis political authorities, especially with regard to the anti-democratic approach axis, which is rated 1 in the figure below, as the Bertelsmann Transformation Index data seems to confirm (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Consensus-building in Egypt, 2024. Source: Bertelsmann Transformation Index.

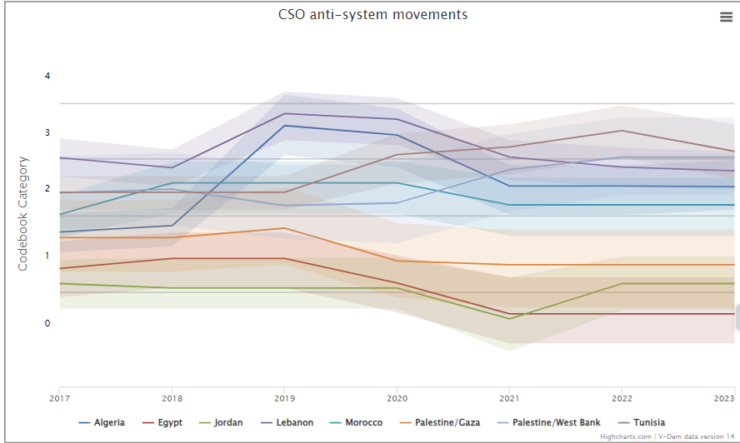

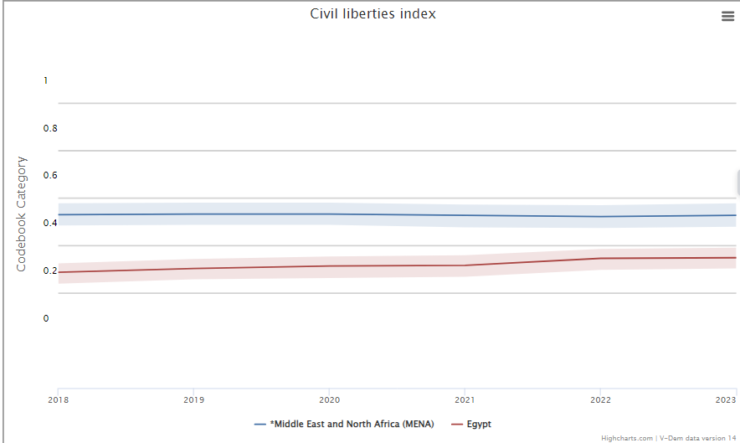

In November 2024, Egypt announced a plan to improve local governance and implement “decentralization” at the World Urbanization Forum in Cairo. With the reorganization of the Civil Society and Civic Participation Platform in 2023/2024, Egypt has entered a model that can be described as “hybrid”, combining the state centralization of local governance (governorates), which was gradually introduced after 2013, with a transversal approach to the management of local areas. The pyramidally-structured reorganization of muhafazat (governorates) as state-controlled, until 2024 allowed for more effective dominance in the organization of local politics, while preventing anti-system organizations and political mobilizations in a period of political change and regime adjustment between 2013 and 2020. The shift in favor of decentralization after WUF 2024 is not an arbitrary decision. The decentralization plan is designed to depend on (i) the private sector and (ii) citizen participation. In both cases, the lines of citizen participation are inevitably regulated by the legal framework that determines the size and identity of the two. Despite the process of institutional weakening that accelerated in Egypt between 2023 and 2024, the data presented by the V-Dem until 2024 on civil society participation and anti-system movements show an incongruence between reformism and the degree of freedoms granted. Along the regional trend and when comparing Tunisia – despite the democratic regression after the 2022 coup.

Fig 4. CSO anti-system movements in the Middle East. Source: V-Dem, 2024

Fig 5. Civil liberties index in the Middle East and Egypt. Source: V-Dem, 2024

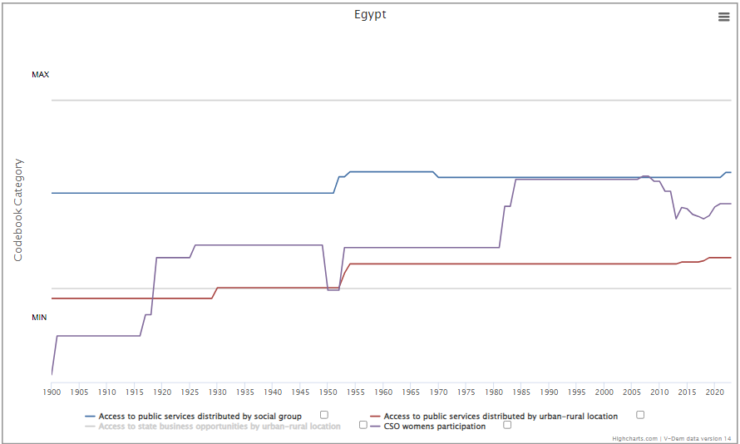

Despite these discrepancies between citizen participation, civil liberties and freedom of action, the general agenda of sustainable development and the approach of sustainable industrialization of the economy, combined with Law No. 149, have enabled the creation of a capillary network of eco-friendly foundations and NGOs that have spread throughout the country. Many of them are international, but among the local foundations, Very Nile is also noteworthy for its progressive projects in support of the blue economy in which Egypt is investing (i.e. marine conservation). At a broader level, the centrality of ecology and the ethics of green development in the political agenda of states mean that institutions reinforce a pluralistic, inclusive approach (i.e. political parties, opposition, feminist groups) while upholding the principles of equity and access to public services even in the face of environmental degradation processes. The data on the diversification of civic inclusivism in the post-2019 period goes in the opposite direction of the premises to which environmental politics adheres. Despite the opening process, environmental activism and the inclusion of women and men in civil society organizations and the workforce have still not been achieved. The proportion of women in the labor force is also still inadequate. Access to public services also deserves to be contextualized. Data extrapolated and combined from the V-Dem dataset suggests that access to public services was indeed limited until 2020/2021 and varied according to selected parameters: it was better when distributed by social groups and communities in non-urban/rural areas, while it was not less efficient when distributed by urban-rural location.

Fig. 6. Combined data on access to (i) services in urban/extra-urban areas and (ii) CSO by women

The revision of the organization of Egypt’s social materiality and the ethical approach to the environment as a component of development on the one hand and urban transformation on the other resonated with international actors, as the environment and the conditionalities attached to the loans supporting industrialization could potentially recalibrate the social pact while changing the contours of authoritarianism. This highlights the contradiction that still pervades Egyptian politics when international and local expectations are contextualized in a context of ongoing and economically driven social crisis.

Curious to dive deeper into how Egypt’s evolving policies are shaping civic life and public opinion? Don’t miss Part Two: The Authoritarian Impact: Does Political Mitigation Really Matter to Egyptians? [Read it here]

Dr Maria Gloria Polimeno is Research Fellow at SOAS University of London and author of “Egypt and the rise of fluid authoritarianism: political ecology, power and the crisis of legitimacy”. Manchester University Press (2024). The views expressed in this piece are her own.