This piece is part of a four-part series published by the Middle East Institute in cooperation with Arab Barometer analyzing the results of the seventh wave of the Arab Barometer surveys.

Apart from Europe and the South China Sea region, the Middle East and North Africa is one of the epicenters for what the U.S. has termed “great power competition” especially between the U.S. and China, although Russia also figures into the assessment. There is particular sensitivity to China’s perceived economic inroads into the region as it has surged to become its largest economic partner. Apart from China’s dependence on imports of Gulf oil to meet its energy needs, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has expanded Beijing’s footprint from Oman in the east to Morocco in the west.

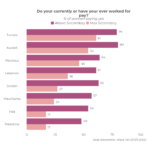

Based on Arab Barometer’s Wave 7 raw favorability numbers, China’s increased presence in the region appears to have paid dividends in terms of its popular standing, especially in North Africa. Except for Morocco, where favorability for the U.S. at 69% is marginally higher than China’s rating at 64%, the U.S. consistently lags behind China in the view of respondents to the 12-country survey. The favorability gap is particularly notable in Algeria, where China enjoys a 20-point edge over the U.S. at 67% vs. 47%. One possible explanation for the broad disparity in favorability ratings for the U.S. between Morocco and Algeria, of course, is widespread anger in Algeria, and the converse in Morocco, over the Trump administration’s December 2020 decision to recognize Moroccan sovereignty in the Western Sahara. The Arab Barometer seventh wave polling was undertaken after that decision, between October 2021 and July 2022.

But even in Tunisia and Libya, where the U.S. has focused a great deal of effort in promoting positive outcomes in their political transitions since the Arab Spring, China is viewed far more favorably than the U.S. (in Tunisia by 50% vs. 33% and in Libya by 49% vs. 37%). Skepticism over the U.S. intent in providing foreign assistance appears to underlie unfavorable views of the U.S. Only 18% of rural and 15% of urban Tunisians agreed that U.S. assistance is motivated by a desire to improve people’s lives whereas a plurality of Tunisians (40% rural and 44% urban) and a majority of Libyans (50% rural and 53% urban) believe the U.S. uses its foreign assistance to gain influence. By contrast, pluralities of Libyans (35%) and Tunisians (40%) saw Chinese objectives in providing foreign assistance as aiding either economic development or internal stability.

One contributing factor in low U.S. favorability ratings is likely the overhang of negative regional sentiments toward U.S. policy in the Trump administration. Broad regional attitudes toward Biden administration policies are notably higher than his predecessor’s poll results. In Sudan, for example, a majority of Sudanese (52%) consider Biden administration policies to be good or very good compared to only 20% who viewed Trump policies in a positive light. In Morocco, Biden’s approval stands at 46% vs. the 14% who viewed Trump favorably despite the Western Sahara decision. Even among populations that continue to hold the U.S. in low esteem, there has been improvement since the Biden administration came into office. In Tunisia, 23% of those polled think that Biden’s policies are good or very good as compared to Trump’s 10% while the similar comparison in Palestine is 11% vs. 6%. In that regard, despite overall improvement in attitudes toward Biden’s regional policies, the vast majority of Palestinians clearly see little reason for optimism in U.S. policy toward their issues since Biden came into office.

Biden’s improved numbers also reflect an uptick in popular perceptions of Biden’s foreign policy as compared to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s policies. A majority of Sudanese (52%) see Biden’s policies as good or very good compared to Xi’s 43%. In Morocco, as well, the public holds generally more favorable attitudes toward Biden (46%) as opposed to Xi (39%). Elsewhere in the region, including, surprisingly, in Jordan and Lebanon, U.S. and Chinese policies are seen in roughly equivalent terms (Jordan: Biden 28%/Xi 26%; Lebanon: Biden 31%/Xi 35%). And Xi is notably more popular with the publics in several countries, including Algeria (Xi 53%/Biden 35%), Iraq (Xi 48%/Biden 35%), and Tunisia (Xi 35%/Biden 23%).

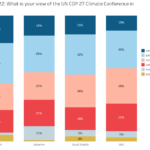

On economic relations, there is clearly a region-wide desire to strengthen relations with global partners. For both the U.S. and China, young people (18-29) generally favor the economic relationships more than their older fellow citizens (30+). Even in Tunisia, nearly 60% of young respondents favor closer economic ties to the U.S, nearly equal to the 65% who would like to see closer economic ties to China. Overall in the region, even in those countries that are generally skeptical of ties to the U.S., there is a desire to seek stronger economic links. In Iraq and Libya, for example, equal numbers of young people want to strengthen economic ties to the U.S. and China. In several other countries, including Morocco, Mauritania, and Sudan, young people clearly favored the U.S. as an economic partner over China.

Despite these seemingly solid favorability numbers overall for the Chinese, however, a public diplomacy professional in Beijing would clearly see warning signs in some of the Arab Barometer measures of popular perceptions. In particular, there appears to be a fairly high degree of ambivalence about their country’s economic relations with China among the publics as compared to the U.S. Notably, there are significant minorities in several of the countries, particularly among rural and less-educated respondents, that would like to see economic links to China reduced. In Lebanon, for example, 23% of respondents with a maximum secondary education and a full third of rural respondents preferred to see economic ties to China loosened. In Iraq, 23% of secondary educated and 21% of rural respondents advocated for reduced economic relations with China, as well.

There are a number of factors that appear to contribute to the ambivalence about China as an economic partner. In all of the countries surveyed, often by wide margins, the Chinese are seen as the country that provides the lowest quality products. In Iraq, for example, 69% of respondents thought that Chinese products were low quality as compared to only 8% who thought of U.S. products that way. Similarly, in Jordan, 64% of survey participants saw China as a producer of low quality products compared to 7% who viewed U.S. products in that light. In the other seven countries surveyed, a plurality of respondents all agreed that Chinese goods were of low quality. Conversely, the U.S. and Germany were seen through all of the nine countries surveyed as producers of the highest quality products. Respondents who viewed Chinese products positively ranged from a low of 8% in Algeria to a high of 18% in Libya.

Similarly, Chinese companies were held in generally low esteem as business partners and employers. For the most part, respondents in the surveyed countries preferred businesses in either the U.S. (Lebanon, Mauritania, Sudan) or Germany (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia) as contracting partners. Only in Iraq did the plurality (27%) of respondents prefer Chinese companies as business partners. Integrity appears to be a factor in that perception as respondents generally saw U.S. (Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Sudan) and German (Algeria, Mauritania, Tunisia) businesses as least likely to pay bribes while Chinese companies lagged behind. Likewise, U.S. (Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Sudan) and German (Algeria, Lebanon, Tunisia) businesses were deemed most likely to pay their local employees top salaries with Chinese companies generally scoring poorly in that regard.

Arab Barometer’s Wave 7 surveys straddled the outbreak of conflict between Russia and Ukraine, so we will have to await Wave 8 to determine if Russia’s war of aggression will affect regional attitudes toward Russia and Vladimir Putin. For the most part, views of Russia and Putin in Wave 7 were not substantially different from views of the U.S. and Biden or China and Xi. In fact, in a number of instances, views of Russia and Putin closely approximated respondent attitudes toward China and Xi. In Lebanon, Algeria, and Libya respondents rated Russian and Chinese favorability in nearly identical terms (Lebanon: China-51%/Russia-52%; Algeria: China-67%/Russia-66%; Libya: China-49%/Russia-49%) while in Iraq and Tunisia, respondents rated Putin and Xi equally (Iraq: Putin-46%/Xi-48%; Tunisia: Putin-34%/Xi-35%). Only in Morocco did U.S. favorability significantly exceed Russia and China (U.S.-69%/China-64%/Russia-38%) while in Jordan, the U.S. and China were rated equally ahead of Russia (U.S.-51%/China-51%/Russia-39%). The same holds true as to the personal favorability estimations for Biden, Putin, and Xi. Only Sudanese and Moroccan respondents held a significantly more favorable view of Biden (Sudan: Biden-52%/Xi-43%/Putin-34%; Morocco: Biden-46%/Xi-39%/Putin-26%).

The same picture also holds among the three competitors in economic favorability ratings. Only in Algeria did a significantly higher number of respondents favor stronger economic ties to Moscow as compared to the U.S. or China (Russia-55%/China-38%/U.S.-31%). In Morocco and Sudan, respondents favored stronger ties to the U.S. (Morocco: U.S.-42%/China-36%/Russia-28%; Sudan: U.S.-58%/China-48%/Russia-45%). Among the other countries participating, there are few distinctions among the U.S., China, and Russia, although China is the preferred partner in Tunisia, Libya, and Iraq. Trend lines may be somewhat more revealing. After enjoying a significant rise in economic favorability during the Obama years (Wave 3 and Wave 4), positive views of U.S. economic ties dropped significantly during the Trump administration (Wave 5) but have now recovered somewhat in the latest (Wave 7) survey. By contrast, both China and Russia saw drops in their economic favorability ratings between Wave 5 and Wave 7, with China experiencing a precipitate decline in its favorability rating in Jordan, albeit from an extremely high 70% favorable to a still respectable 50%. Aside from Tunisia, where its favorability rating essentially flat-lined from Wave 4 to Wave 7, Russia’s favorability has also declined between Wave 5 and Wave 7.

A recurring theme in discussions with interlocutors in the region is that the MENA countries will resist becoming a battleground in a “great power competition” between the U.S., Russia, and China. Although there are clearly differences in how the three competitors are viewed in the region, it’s also clear that public opinion in the Arab Barometer Wave 7 survey echoes the views of political leaders that they seek to maintain positive political and economic relations with all three. As noted, the potential impact of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine on MENA popular attitudes remains to be measured. But that variable aside, unlike the post-World War II Cold War era, these populations will favor strongly remaining non-combatants in any new cold war.

Amb. (ret.) Gerald Feierstein is a distinguished senior fellow on U.S. diplomacy at MEI and director of its Arabian Peninsula Affairs program.

Read original article at mei