Education May Not Be Sufficient, But It Is Necessary

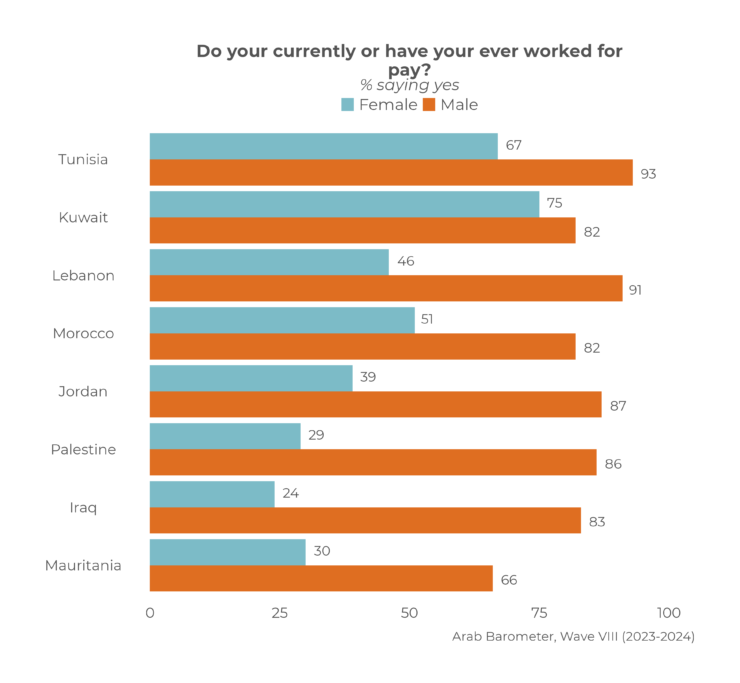

The gender gap in workforce participation across the Middle East and North Africa is among the largest of any region in the world. In the latest Arab Barometer survey, the average difference between men and women reporting to have ever held a job is over 38 percentage points. This difference increases to just over 43 percentage points if Kuwait is dropped[1].

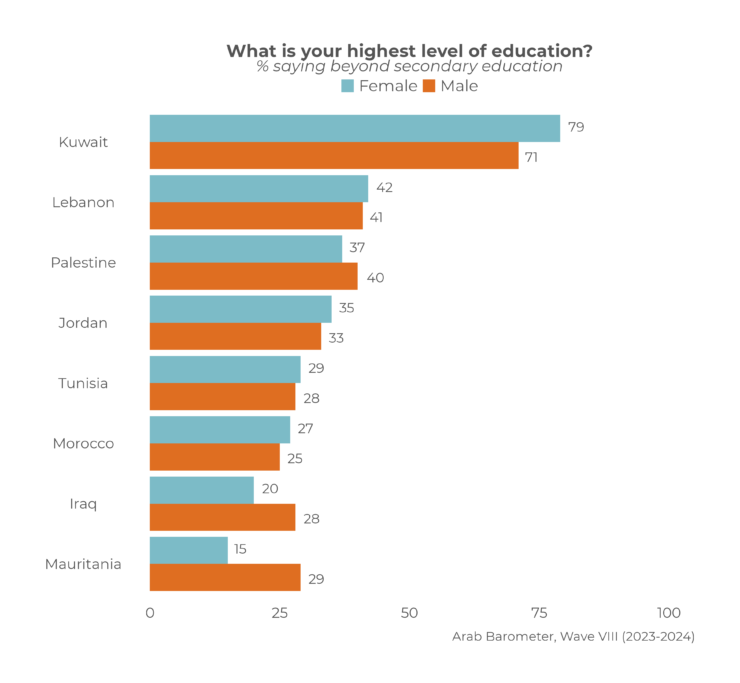

At the same time, women across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are achieving education beyond a secondary degree at, or in many cases above, the same rate as men. According to the latest available data from the World Bank, the gender parity for tertiary schooling is above the world average in six countries surveyed by Arab Barometer in 2023-2024 (there is not data available for Iraq). Mauritania is the only country in Arab Barometer’s latest data that falls below the world average. In stark contrast, every country falls below the world average ratio of FLFP to male labor force participation according the latest available data from the World Bank. The gulf between gender parity in schooling versus labor force participation is described as the MENA Paradox in the literature on gendered employment.

The MENA Paradox literature frames the question of the persistent gender gap in employment as a supply and demand puzzle, focusing intently on demand. Scholars argue that the supply of well-educated women definitively exists, so there must be an issue with the demand for educated workers conditional on their gender. A university or professional degree is clearly not a sufficient condition for women to successfully join the labor force in MENA.

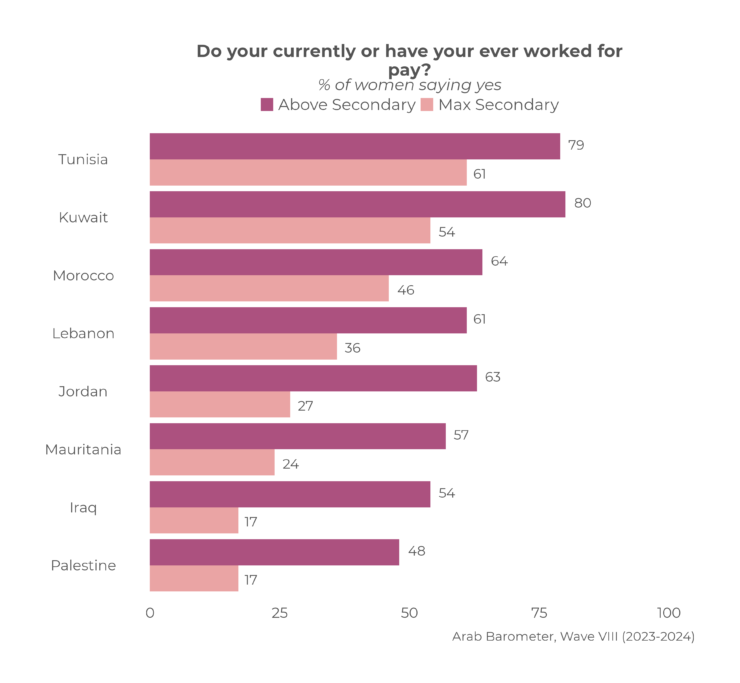

Arab Barometer’s latest survey demonstrates that while perhaps not sufficient, higher education is absolutely necessary for women to participating in the labor force. Across all countries surveyed, there is a 28-point average difference between those with more or less than a secondary education in women reporting to have held a job at any point. The smallest difference is seen in Tunisia and Morocco, where women with above a secondary education are 18 points more likely to say they either currently work or worked in the past. On the other end, there is a 37 and 36-point difference in Iraq and Jordan, respectively, between women with and without higher education with regards to work experience. In contrast, there is only a four-point difference on average in employment history between men with more and less schooling.

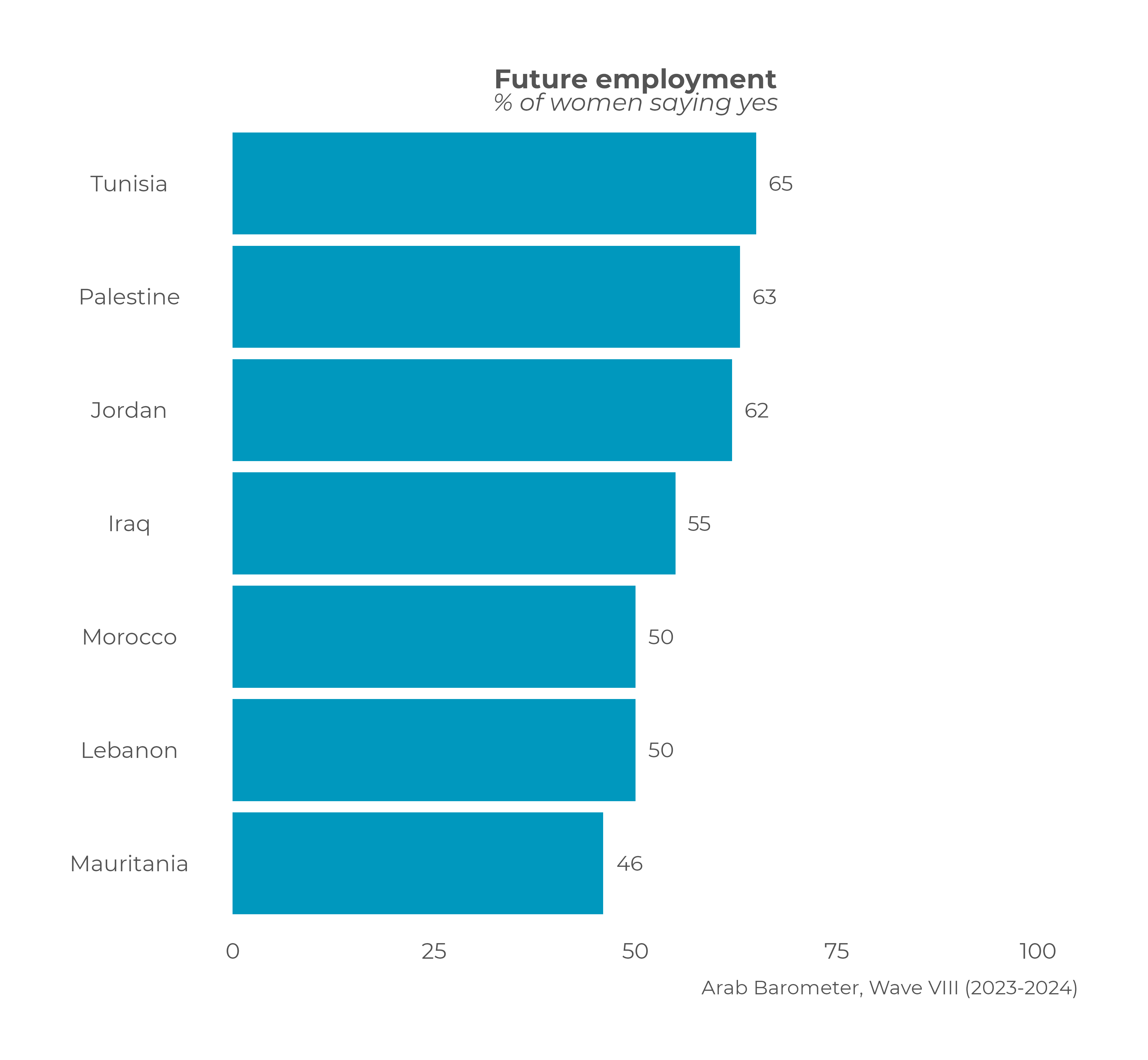

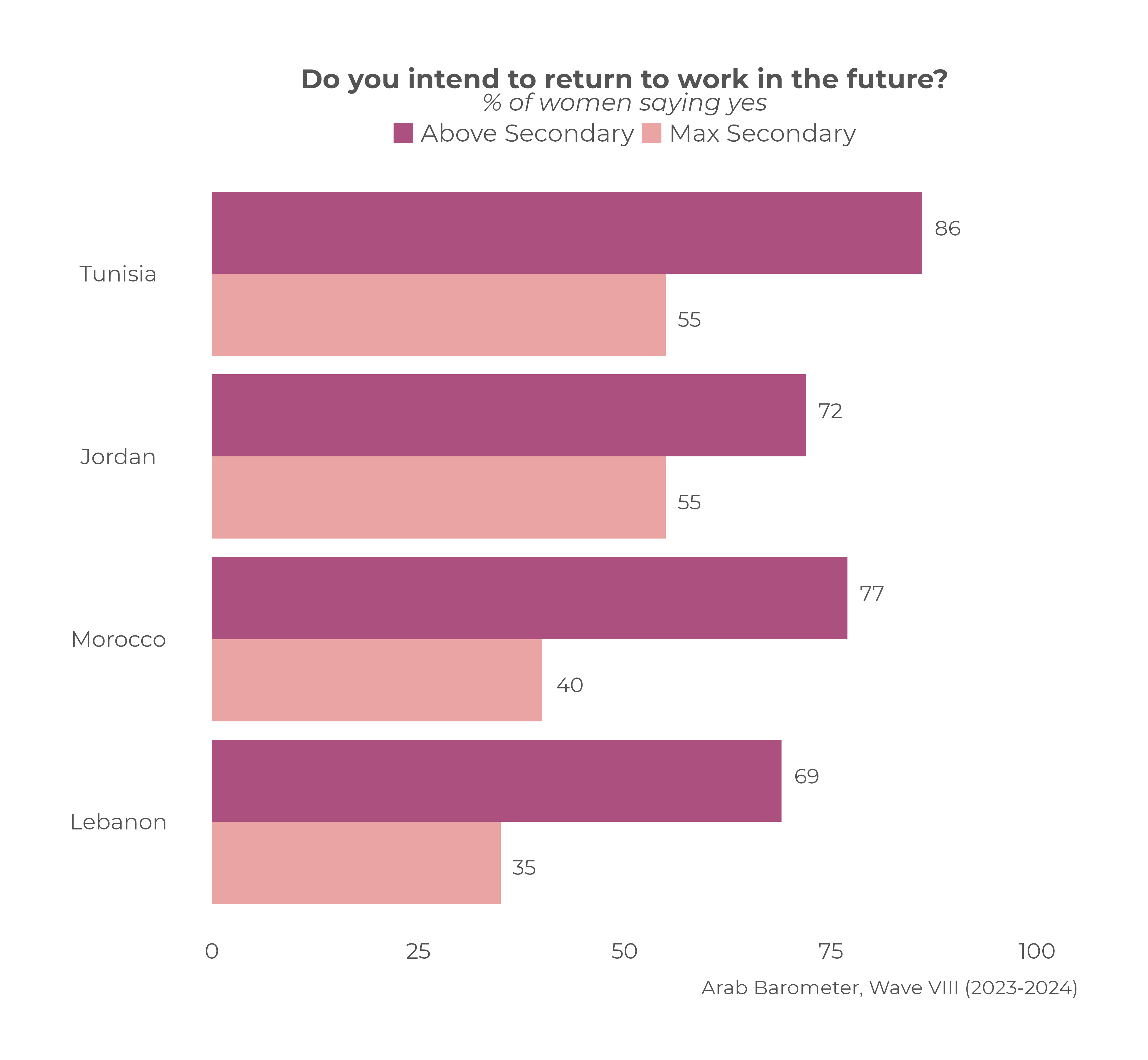

Further evidence of the importance of education for women’s participation in the labor force is seen when women who are not currently working for pay are asked if they would like to return to work. In most countries surveyed, at least half of women who say they have held a job in the past say they intend to return to work in the future. Among the four countries with a large enough sample size to analyze, women with above a secondary education are likely than women with at most a secondary education by 37 points in Morocco, 34 points in Lebanon, 31 points in Tunisia, and 17 points in Jordan.

Women with greater educational attainment not only join the labor force at greater rates than women with less education, but intend to return to work at higher rates as well. The other side of the coin implies that women with less education are less likely to be join the labor force, and, even if they have in the past, they are less likely to return to work. The staggering difference in workforce participation by women according to education levels underscores the importance of continuing to encourage women towards higher education. Despite women’s increased educational attainment not translating directly into increased female labor force participation, education remains a crucial factor for women’s employment.

[1] Kuwait is a Gulf nation with a historically different approach to female labor force participation and notable outlier compared to the other seven countries surveyed.