In a televised address on May 10, Kuwait’s Emir, Sheikh Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, firmly stated, “I will not let democracy be exploited to destroy the state.” This address came as he dissolved the National Assembly for the second time in three months and enacted temporary suspensions of specific constitutional provisions for up to four years. Subsequently, the Emir sanctioned the formation of a new cabinet and articulated his determination to pursue reforms. This stance not only underscores his willingness to push through controversial policies but also signals a strategic pivot aimed at reducing the nation’s dependence on oil revenues.

The suspension of the parliament has elicited surprise among some Kuwaitis and Kuwait observers. After all, Kuwait has long been hailed as a bastion of democracy within a region characterized by a trend toward authoritarianism following the Arab uprisings. In stark contrast to its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) counterparts, Kuwait boasts a parliament endowed with legislative powers, capable of engaging in the formulation, deliberation, and enactment of laws. It can also interpellate cabinet ministers and cast votes of no confidence, which often led to ministerial resignations. Just a month prior, on April 4, the nation had held snap elections to elect a new parliament. Kuwaitis take great pride in their democratic traditions, including political openness and freedom of expression. Nowhere else in the GCC do citizens enjoy comparable rights.

Some observers, however, might have seen the decision to suspend parliament as a culmination of longstanding tensions and disagreements within Kuwait’s political system. Persistent gridlocks between the elected members of the parliament and the government have gripped the nation for years, including over economic reforms. Notably, since 2006, the National Assembly has been dissolved ten times and nullified three times by the Constitutional Court, emblematic of the ongoing challenges besetting the nation.

In “Will Kuwait’s Next Parliament Be Its Last?”, a Journal of Democracy Online Exclusive from March 2024, Sean Yom rightly predicted the suspension of the parliament. Scrutinizing the historical context of Kuwait’s democratic journey, marked by recurrent legislative crises and political upheavals, he raised valid concerns about the sustainability of its parliamentary democracy. Yom also predicted that if the Emir were to suspend parliament, Kuwait might face considerable opposition. Nevertheless, street protests have not materialized thus far, and Kuwaitis have largely exhibited a subdued response on social media platforms regarding the parliamentary suspension.

Where might the public stand? Our latest survey, conducted in collaboration with Tarek Masoud of Harvard University and the Arab Barometer, offers valuable insights. Administered prior to Ramadan this year, the survey unveils a nuanced picture: while respondents convey disillusionment with the parliament, they simultaneously underscore the significance of electoral processes.

Our data includes 1210 face-to-face interviews conducted between February 14 and March 18. The survey employed probability sampling techniques to ensure representation of Kuwaiti nationals aged 18 and above. It included a wide range of questions aimed at gauging the attitudes of ordinary Kuwaitis on political, economic, and social matters. It is worth noting that Kuwait stands as the sole GCC country where such comprehensive, nationally representative public opinion surveys are readily accessible, underscoring the importance of this research endeavor.

Kuwaiti sentiments toward the parliament’s performance are characterized by discontent.

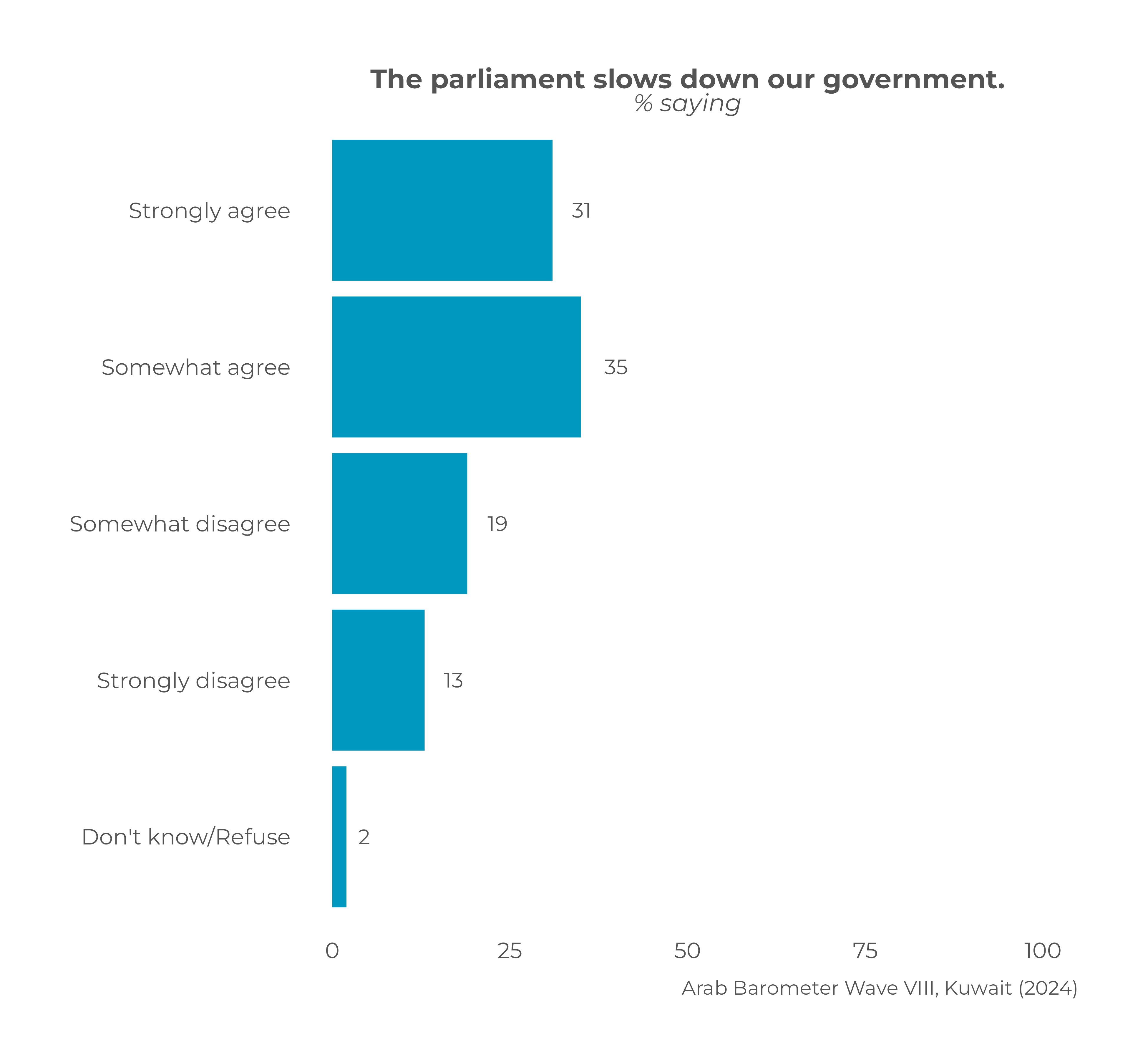

We asked a series of questions to probe Kuwaitis’ perspectives on the National Assembly. Most notably, a striking 66 percent of Kuwaitis “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed with the statement that the National Assembly slowed down the government. This prevailing sentiment of disapproval remains consistent across demographic segments, regardless of age, income level, or educational attainment, suggesting widespread disillusionment with the parliament’s performance.

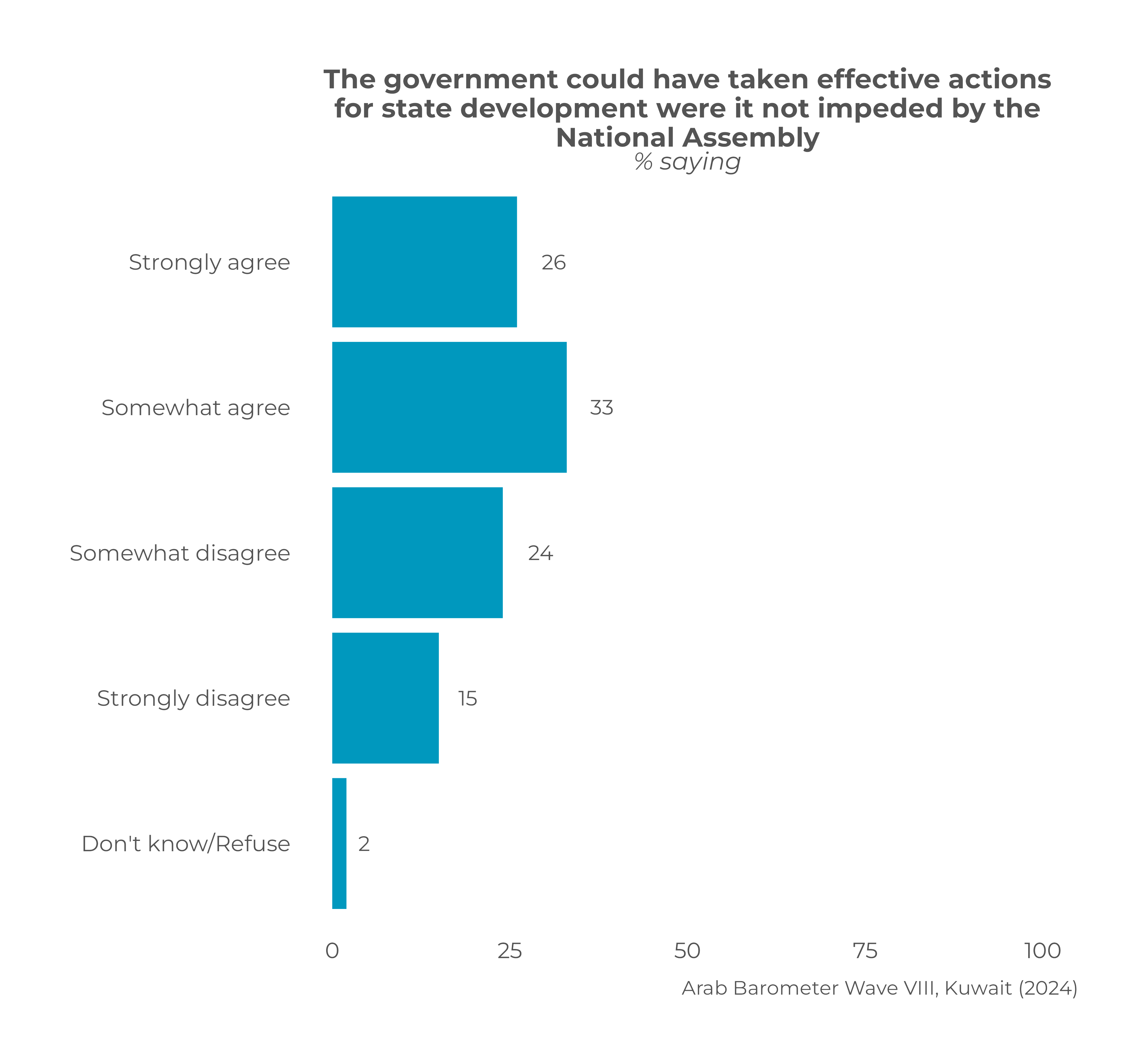

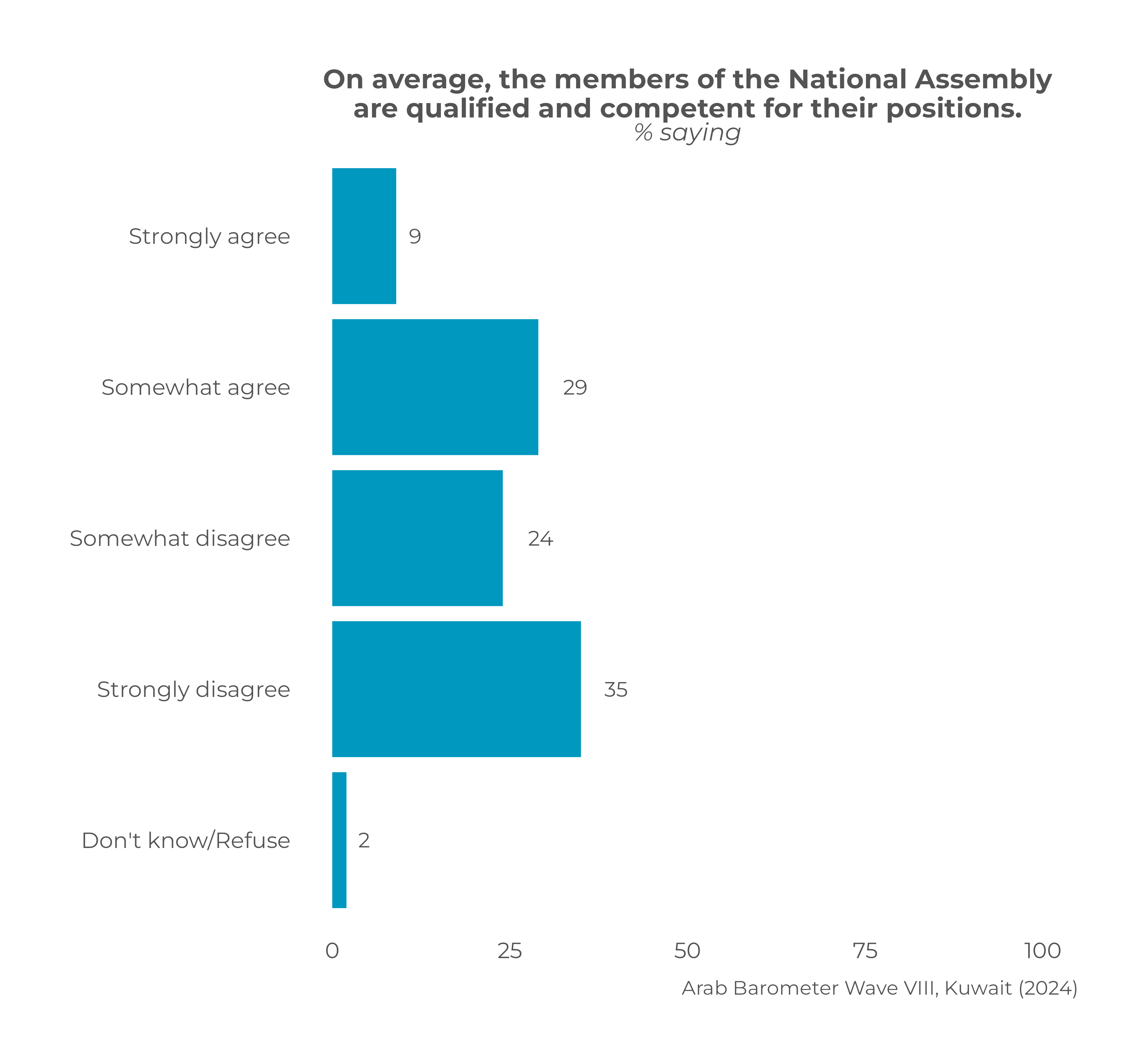

Similarly, 60 percent agreed that “the government could carry out effective actions to advance the state if it were not held back by the parliament.” Furthermore, a mere 39 percent agreed that members of the parliament were qualified and competent for their positions, in contrast to the 50 percent who held a similar view regarding government ministers. These were our original questions, not included in previous waves of the Arab Barometer.

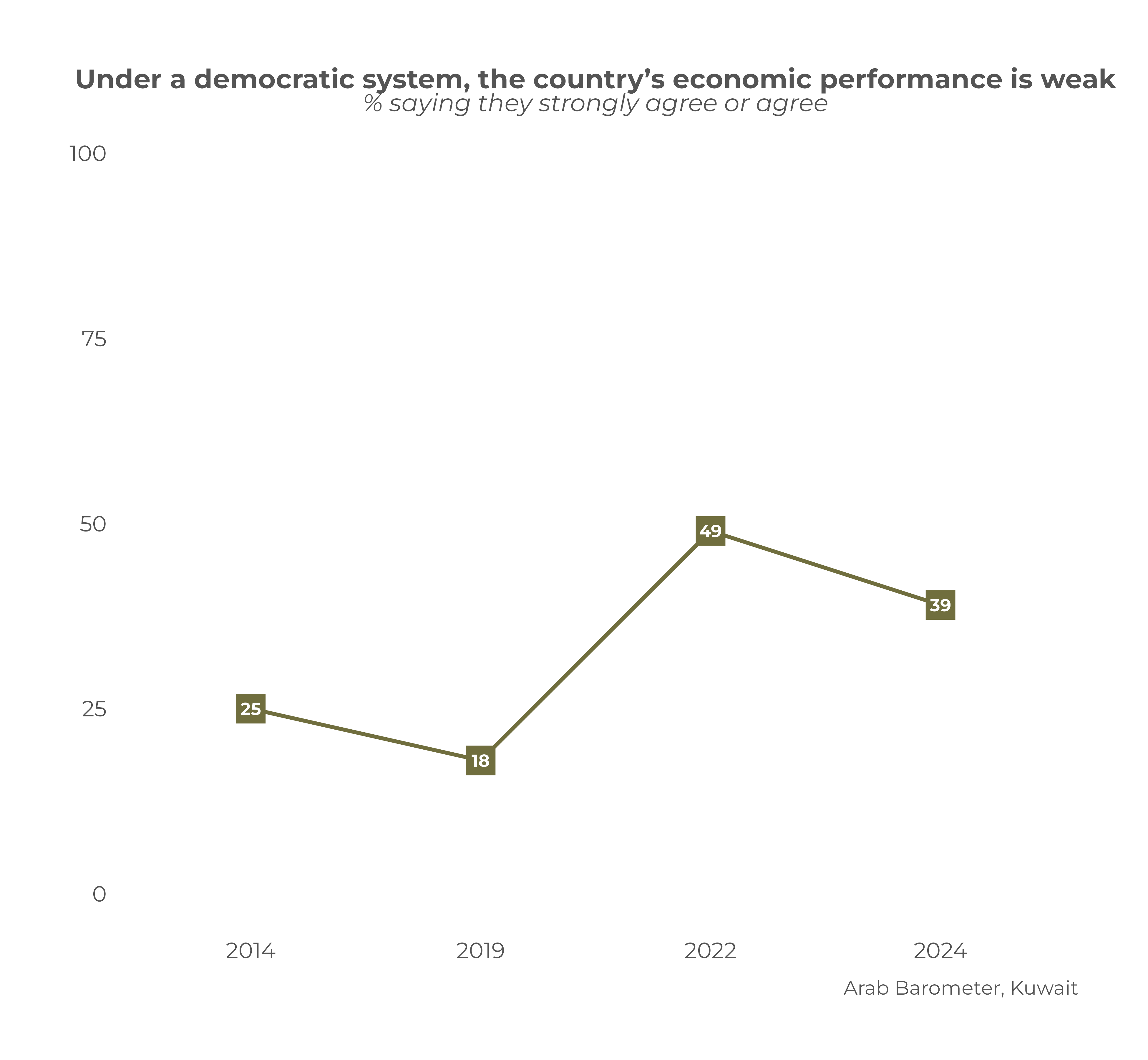

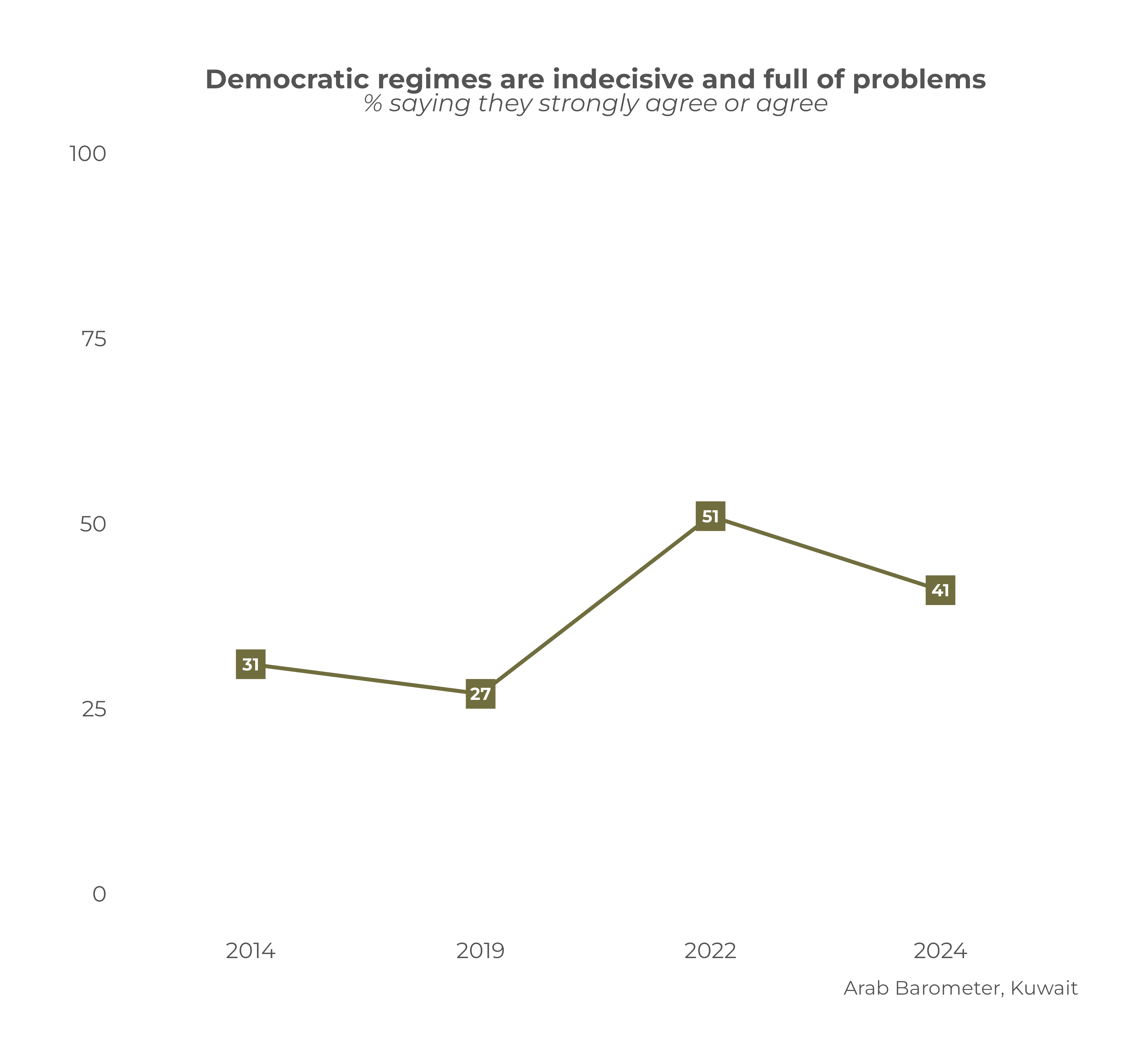

A distinctive advantage of collaborating with the Arab Barometer lies in our ability to conduct longitudinal analyses, enabling comparisons of responses over time. For instance, when respondents were prompted to either agree or disagree with the statement, “democratic regimes are indecisive and full of problems,” 41 percent agreed or strongly agreed. This marks a notable increase from the 27 percent who had agreed with the statement when the same question was asked in the Arab Barometer’s 2018 survey. Similarly, in response to the statement that “under a democratic system, the country’s economic performance is weak,” 39 percent agreed in the recent survey. Interestingly, a significantly lower proportion, only 18 percent, expressed agreement with the statement in 2018.[1]

The results do not mean that Kuwaitis are ready to part with their democratic principles.

Our findings thus far indicate that Kuwaitis acknowledge the imperfections within the country’s democratic framework. What implications might these results carry for the future of democracy in Kuwait? Will Kuwaiti society acquiesce to authoritarian alternatives? While Kuwaitis undeniably harbor frustration over recent parliamentary impasses, they also express a resolute endorsement of Kuwait’s democratic heritage. In particular, 66 percent of Kuwaitis agreed that “the parliament provides important oversight of the government.” Moreover, an overwhelming majority perceive the “ability to freely choose political leaders in elections” to be a very essential pillar of democracy or human dignity.[2] Similarly, a remarkable 85 percent agreed with the statement that “democratic systems may have problems, yet they are better than other systems.”[3] Historically, during periods of National Assembly suspension by Kuwaiti rulers (1976-1981; 1986-1991), the populace consistently managed to reinstate it, a testament, perhaps, to their enduring tradition of consensus-building that predates the constitution.

Furthermore, when asked about the culpability for Kuwait’s recent “political instability, resulting in the formation of five governments in one year and three parliamentary elections in three years,” 69 percent attributed responsibility to both the government and the parliament. Subsequently, when evaluating potential measures to rectify the situation in Kuwait, 64 percent identified that “Emiri intervention to stop the implementation of government decisions” would help to a great extent, while 57 percent also answered that “new parliamentary elections based on a new election law” would help greatly. Kuwaitis understand that the complex interplay between the elected assembly and the cabinet of ministers likely shaped the country’s recent political tumult. They recognize that both entities bear a shared responsibility for the myriad challenges and disruptions that have characterized Kuwait’s recent political landscape.

In the absence of parliamentary scrutiny, the government could potentially implement long-awaited economic reforms and other initiatives. However, the accountability for governmental performance now rests squarely on the shoulders of the executive branch. This elevated responsibility increases the pressure on the government to demonstrate effective leadership, address societal concerns, and tackle pressing challenges. Consequently, the government must navigate this period of political transition with diligence and transparency, aiming to rebuild public trust and steer the nation toward progress.

Yuree Noh is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Rhode Island College and Research Fellow at the Middle East Initiative at Harvard. Beginning in Fall 2024, she will be Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Utah. Her research focuses on electoral institutions, gender & politics, and public opinion in the Middle East and North Africa.

[1] Please note that unlike in 2018, the questions in 2024 were posed only to about half of the respondents (n=601).

[2] The sample was split in half. Respondents were asked whether the ability to freely choose political leaders was an essential pillar of either democracy (n=609) or of human dignity (n=601). In the divided sample, 82 and 79 percents, respectively, answered that it was a very essential for democracy or dignity.

[3] This question was only asked to half of the respondents (n=601).