The Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) has seen an increase in levels of religiosity, particularly among youth, over the last five years. What implications might this have for the region? Does this rise in personal religiosity correspond with changes in views about the proper role for religion in politics? Might this change foreshadow a revival in fortunes of political Islam across the region?

Results from nationally representative public opinion surveys from Arab Barometer Wave 7 strongly suggest that political Islam is making a comeback. In most countries surveyed, citizens both young and old demonstrate a clear preference for giving religion a greater role in politics. This is the first time that support for political Islam has increased meaningfully across in the period since the Arab Uprisings of 2011. Although these trends may not continue, if they did, political Islam could regain its importance as a major political force in the region.

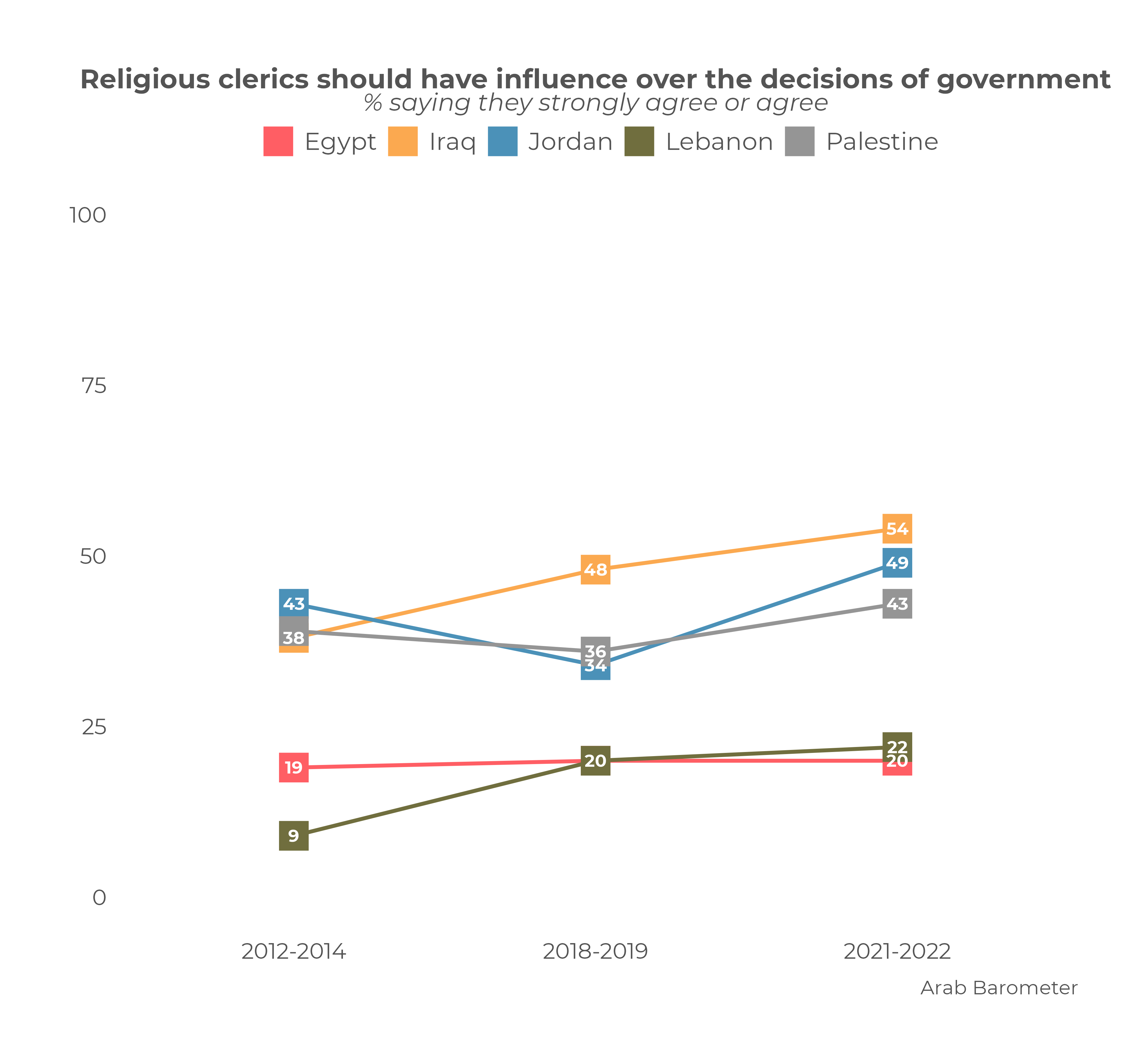

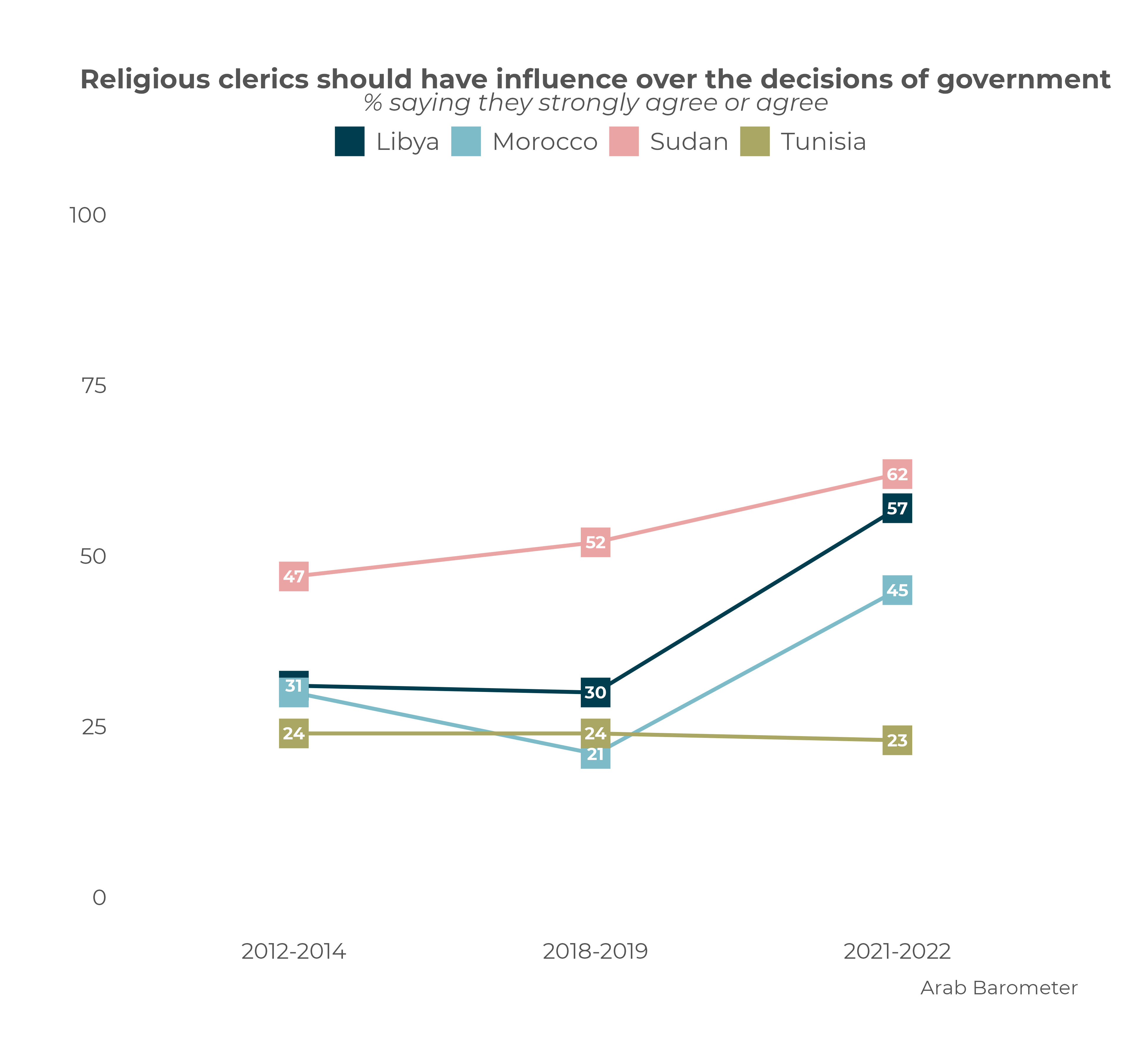

Despite electoral success of the Islamist movement after 2011, political Islam was not widely supported across the region. In 2012-2014, in no country surveyed did a majority of citizens favor giving religious clerics say over decisions of government. In essence, this question asks if religion should play a greater role in politics, which represents the fundamental ideology underlying political Islam. Notably, only in Sudan (47 percent) and Yemen (48 percent) did more than four-in-ten citizens favor this role for religious leaders.

For the most part, this perception remained effectively unchanged by the end of the decade. In 2018-2019, only in Sudan did at least half say they supported giving religious leaders say over decisions of government. Compared with 2012-2014, support did not change by more than five points in six of nine countries surveyed. The exceptions were Morocco, where support fell by nine points, and Lebanon and Iraq where support increased by 11 points and 10 points, respectively.

Today, Islamist parties play a far smaller role in the region’s politics than in the years following the Arab Uprisings. The Muslim Brotherhood is now outlawed in Egypt; Ennahda has faced a crackdown in Tunisia, and the PJD lost parliamentary elections in Morocco. With notable exceptions in Lebanon and Gaza, Islamist organizations no longer play a major role in government across the region.

Might this return to opposition provide an opening for a greater appeal for political Islam? Data from Arab Barometer strongly suggest this possibility. Since 2018-2019 support for the ideology of political Islam has been on the rise. In 2021-2022, roughly half or more in five of ten countries surveyed agreed that religious clerics should have influence over decisions of government, including 77 percent in Mauritania, 62 percent in Sudan, 57 percent in Libya, and 54 percent in Iraq. Only in Tunisia (23 percent), Lebanon (22 percent), and Egypt (20 percent) did fewer than four-in-ten want religious leaders to play a role in making governmental decisions.

Notably, these levels represent an increase from the levels observed in 2018-2019 in six of the nine countries that were included in both waves. The increase is greatest in Libya (27 points) followed by Jordan (15 points), Morocco (14 points), and Sudan (10 points) while smaller rises exist in Palestine (7 points) and Iraq (6 points). At the same time, support for giving religious leaders a greater role in politics did not decline in any country. In the remaining three – Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia – the difference falls within the survey’s margin of error, meaning there was effectively no change in support. In other words, in no country has support for religion in politics declined across the MENA region.

While youth ages 18-29 have led the return to religion across MENA, the rise in support for religion in politics is more widespread across society. In most countries, both older and younger members of society are shifting their views in concert. Youth are more positively dispositioned toward a role for religion in politics in six of the nine countries included in both waves of the survey. Youth in Libya have seen the biggest gain in support (22 points), followed by those in Morocco (20 points), Jordan (19 points), Sudan (10 points), Palestine (8 points), and Egypt (6 points). In Tunisia, Iraq, and Lebanon, the difference falls within the margin of error, meaning there has been no effective change.

For those who are ages 30 and older, the results are relatively similar. There has been a meaningful increase in support for giving religious leaders say in politics in Libya (+32 points), Morocco (+24 points), Jordan (+14 points), Iraq (+11 points), Sudan (+9 points), and Palestine (+7 points). In Lebanon the increase is just outside the margin of error (+3 points), in Tunisia there is no effective difference, and in Egypt the difference in decrease is slightly greater than the margin of error (-3 points).

Overall, these results suggest that support for political Islam is now on the upswing. However, this does not necessarily mean that political Islam as an ideology will grow to be the popular movement it was in the time . As with the rise in religiosity observed in the last five years, it is possible that this trend will reverse in the future. But, in the last few years there has been a clear warming of hearts and minds across the region toward the role religion should play in politics.