Egypt’s National Nutrition Institute (NNI) recent recommendation to “eat chicken feet” as a budget-friendly form of protein animated pundits and the public this past December 2022. The attempt to help citizens navigate increasingly dire economic conditions was lambasted and ridiculed. The declaration, which was put forward earnestly, highlighted just how grim Egypt’s predicament had become.

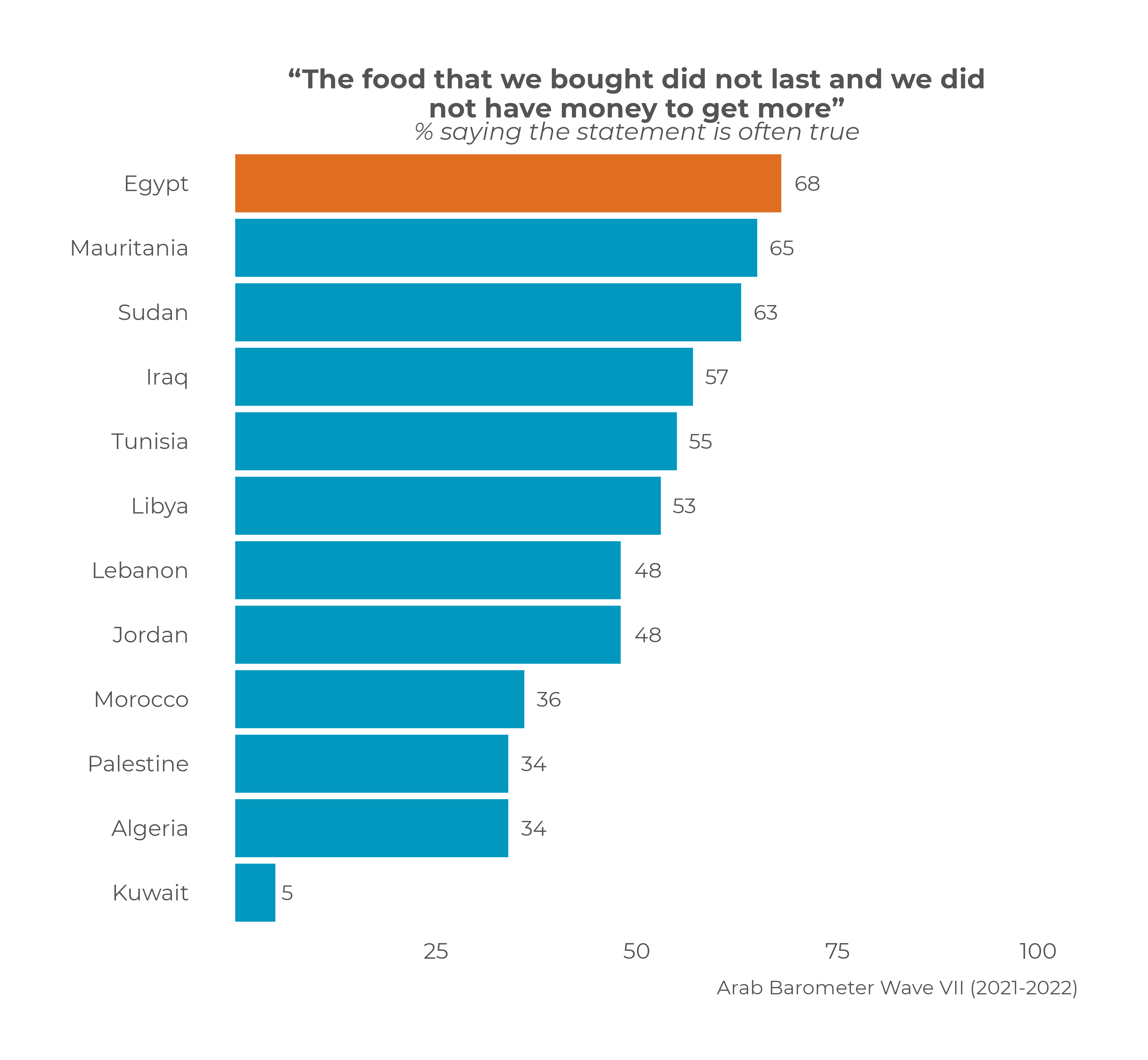

Fielded 11 months before the National Nutrition Institute’s now infamous Facebook post listing meal alternatives, Arab Barometer’s January 2022 survey in Egypt reveals that Egyptian citizens were already feeling the strain of deteriorating economic conditions long before being told to brace for hard times. A significant majority (68 percent) report they often or sometimes ran out of food before having money to buy more, making them food insecure per FAO’s definition. Of all countries surveyed, Egypt is home to the fewest number who have savings or can afford to cover expenses. Citizens perceive that inequality is on the rise, and while pluralities of Egyptians want the government to tame inflation and increase subsidies, neither requests are likely to be fully met in the immediate future.

Arab Barometer’s findings come in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, the direst consequences of which were inflation, according to 40 percent of Egyptians, and loss of household income, according to just over a quarter (26 percent) of citizens. Still, survey was fielded prior to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the two countries on which Egypt was reliant for 80 percent of its grain imports. With continued supply chain disruption and rising costs, there is plenty of evidence to hypothesize that the share of food insecure Egyptians is at least as high today, and their concerns about inflation and income well-founded.

Inflation hit 21.9 percent in December 2022, up from 6.5 percent just one year earlier and reaching a record high since 2017. Meanwhile, the Egyptian pound has depreciated to a historic low against the dollar. Food prices have soared, up 31 percent on average in comparison to 2021. The fluctuation in particular items is more drastic: in January 2023 poultry rose to 75 Egyptian pounds per kilogram, up from 35 pounds one year ago (US$1= 30 Egyptian pounds). Eggs have become a luxury. Costs of meat, rice, sugar, and oil have all also increased.

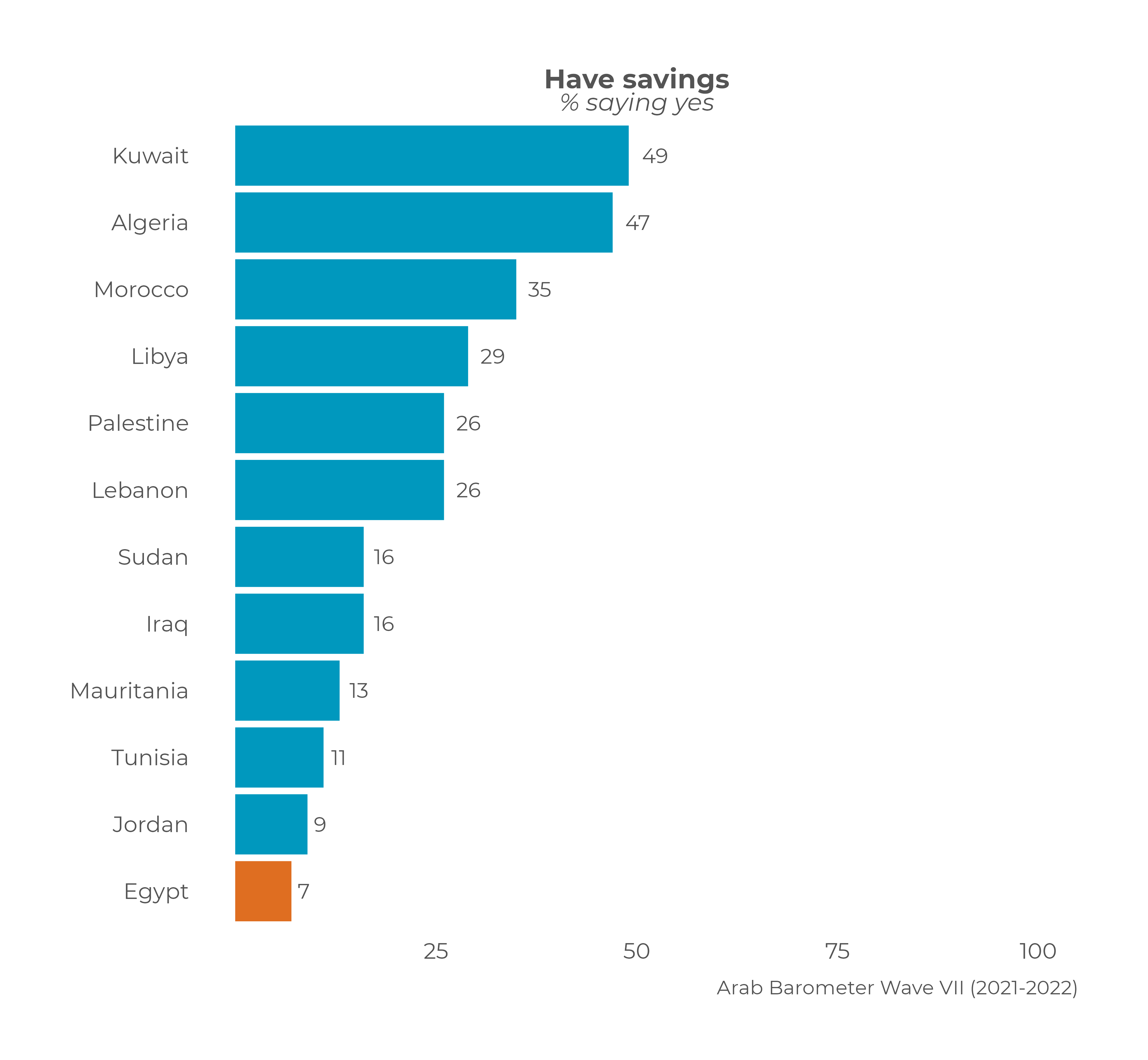

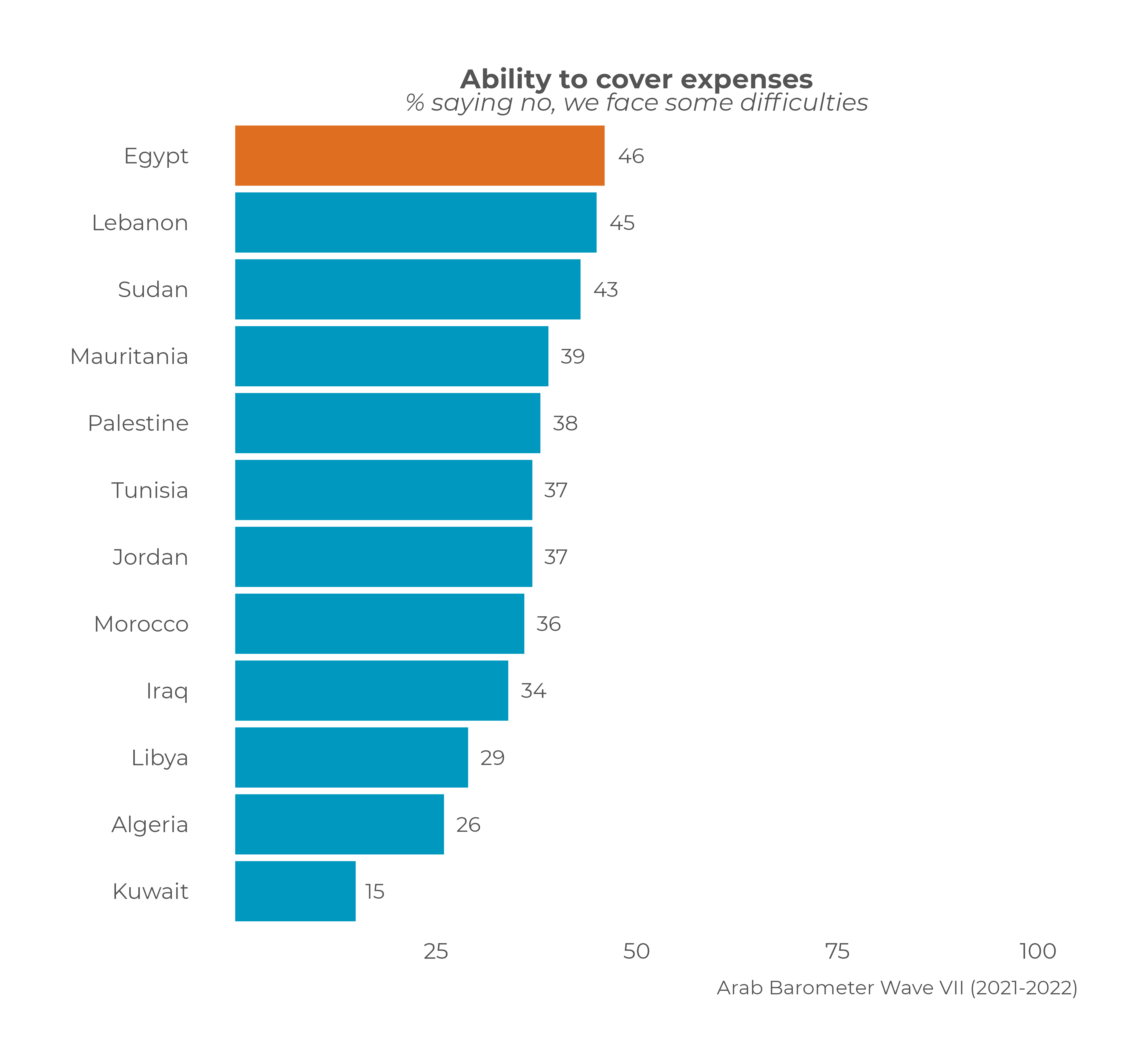

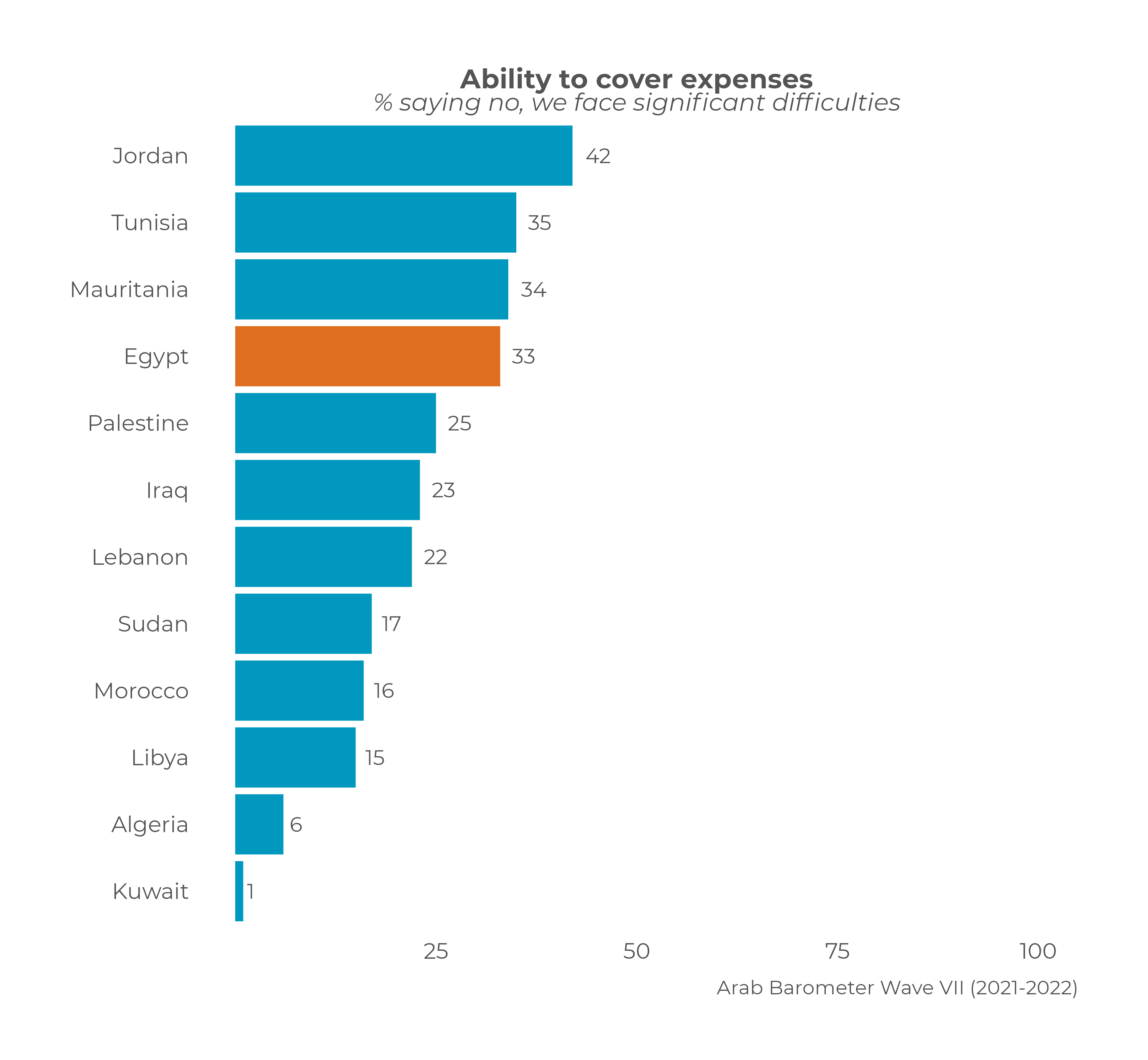

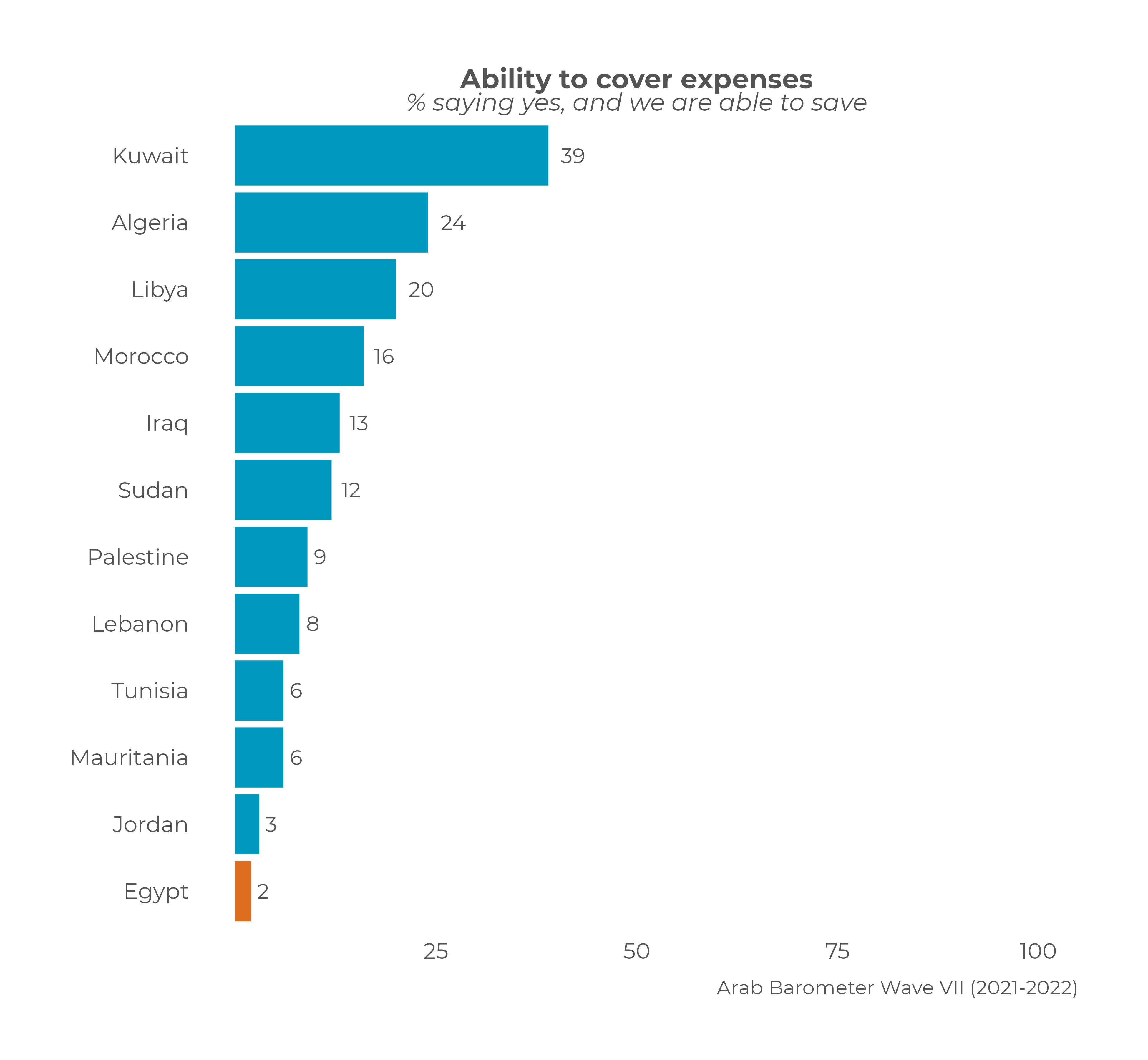

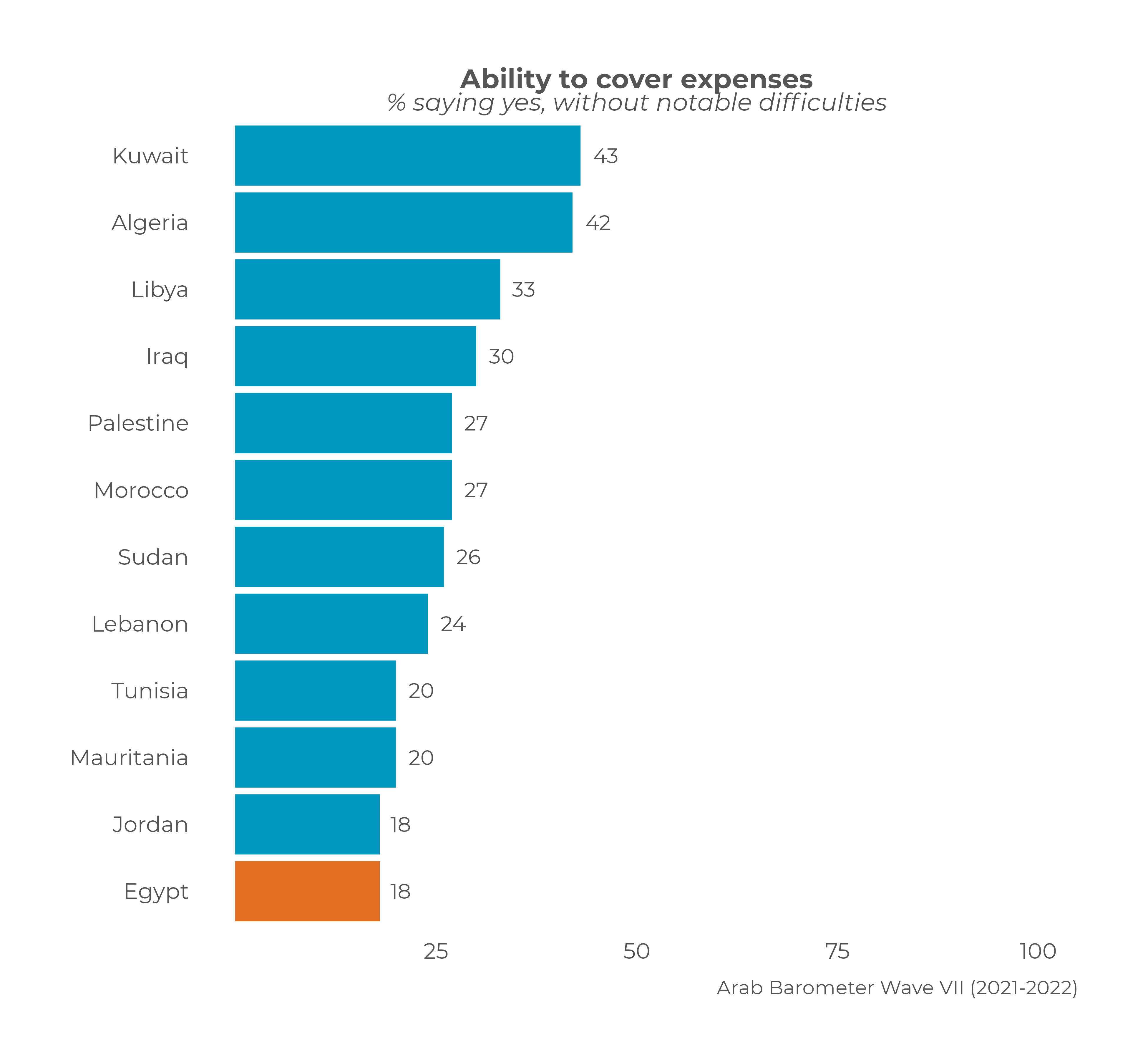

In sum, it has become harder to buy food where there were already few safety nets in place. Arab Barometer findings suggest that just 7 percent of Egyptians report having any savings. Household income is stretched thin: just 2 percent say they are able to cover their expenses and save, and a slightly higher but nonetheless small minority (18 percent) say they can cover their expenses without noticeable difficulties. The remaining majority faces significant difficulties in covering basic needs or simply cannot do so. On these measures, Egypt ranks lowest on the list of all surveyed countries in Arab Barometer’s 2021-2022 surveys.

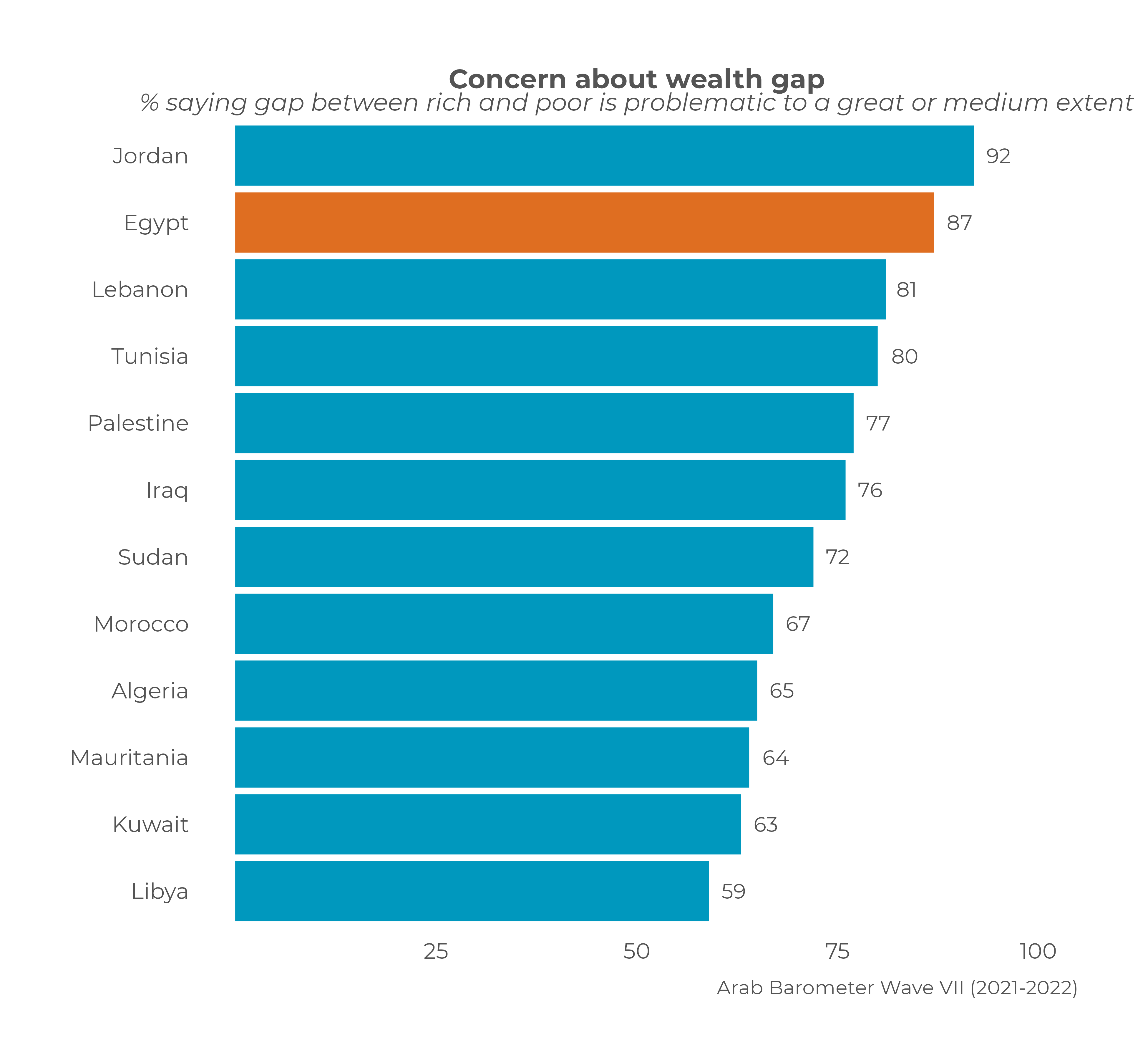

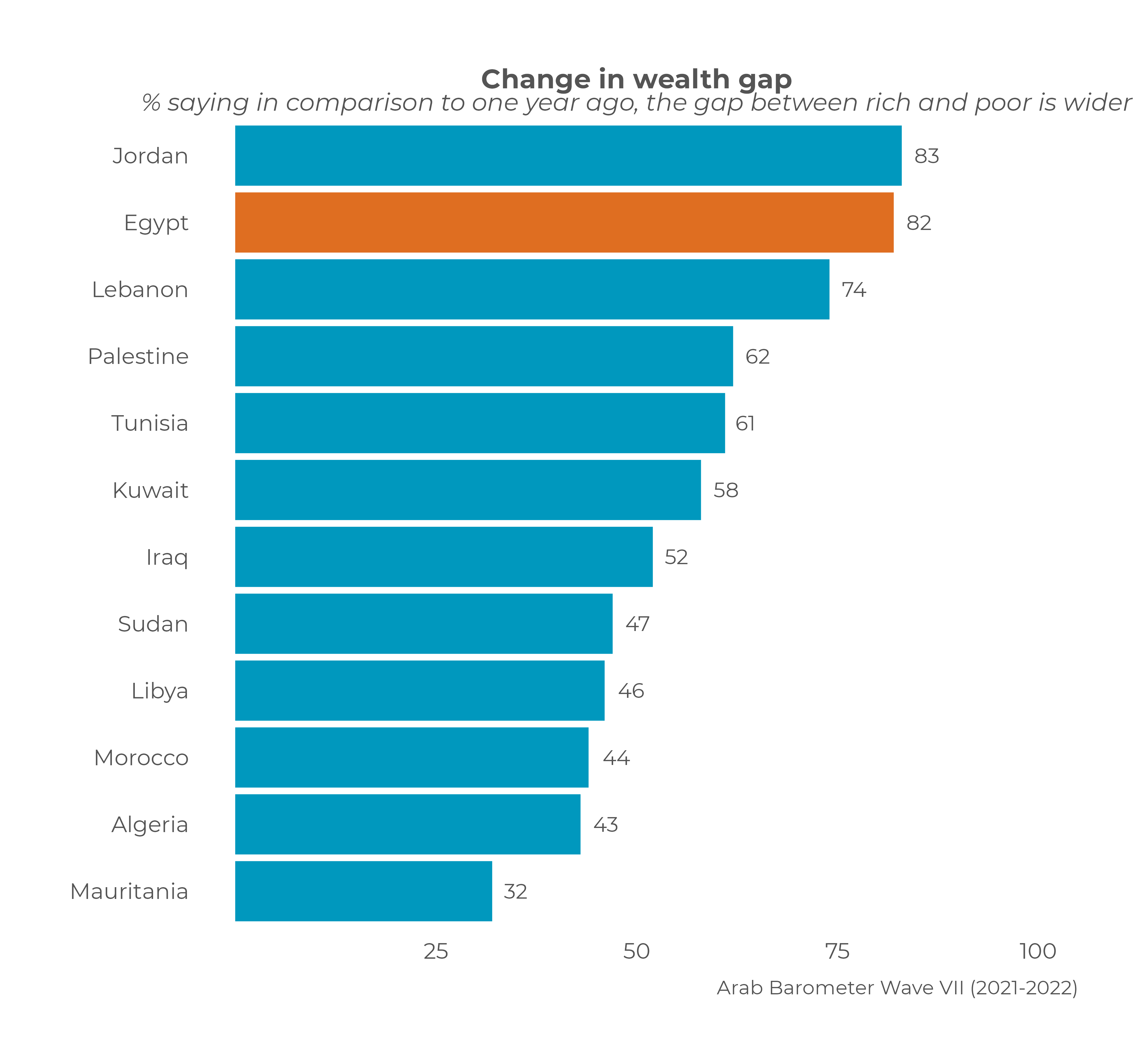

When a necessity as basic as food becomes increasingly difficult to come by, increasingly large disparities in class are often lurking: affordability rather than availability of food is a key cause of food insecurity. Egypt is no exception. Regionally, Egypt has the second highest share of citizens perceiving socioeconomic inequality: 87 percent of Egyptian citizens say that the wealth gap between the rich and the poor is problematic, and a staggering 82 percent say that the gap has grown wider in just the past year.

What Egyptians want their government to do about it

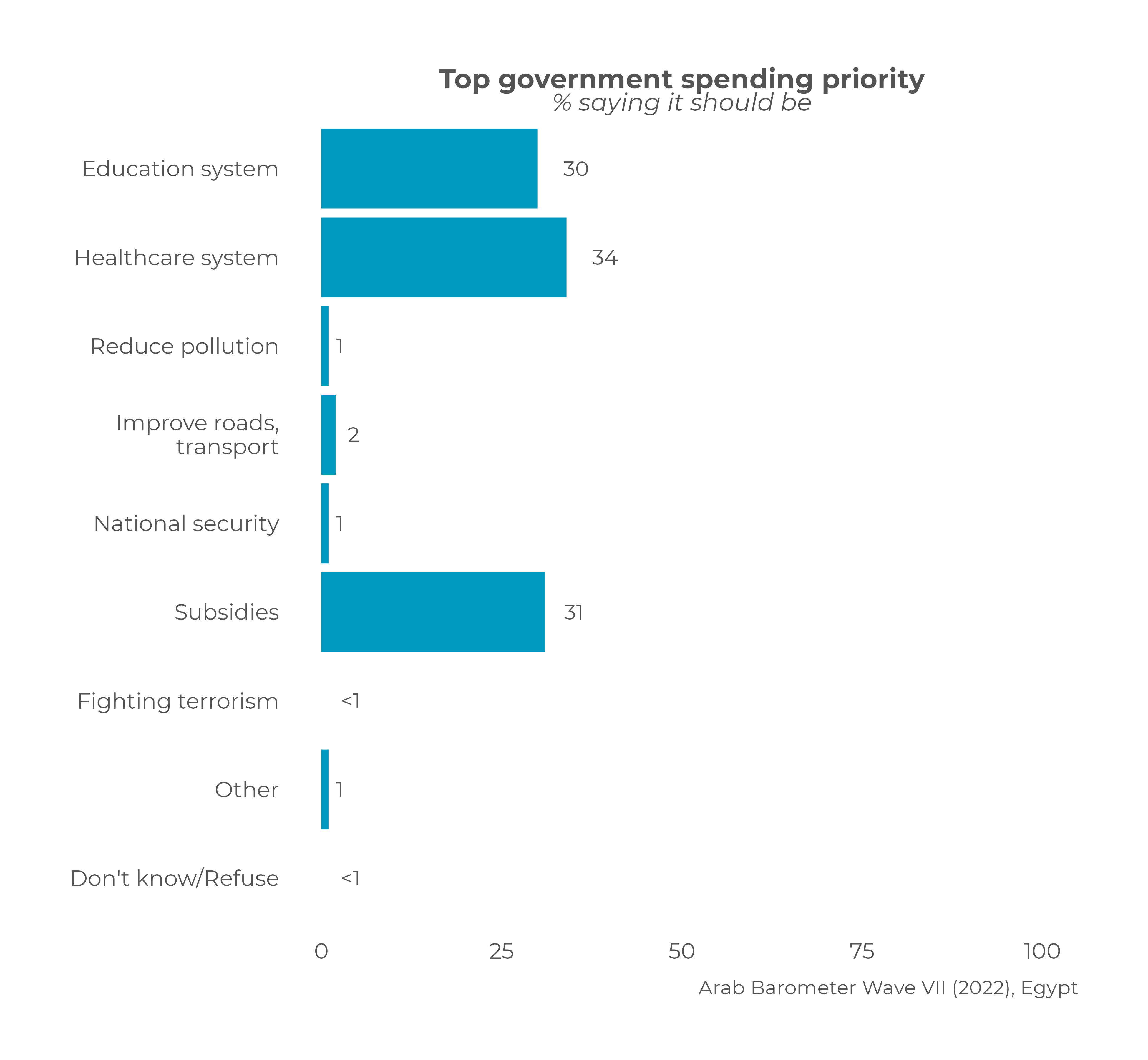

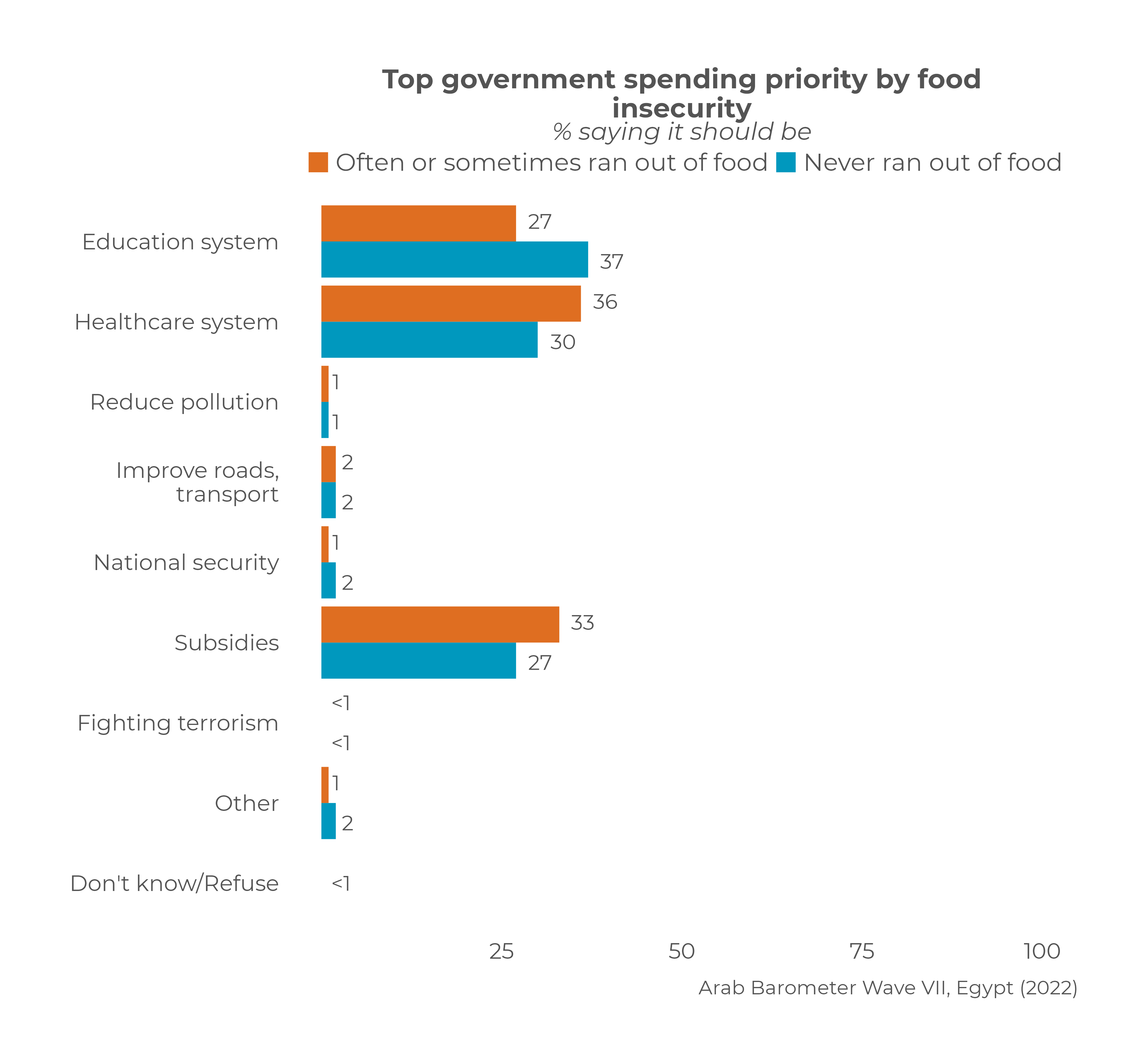

Egyptians are nearly evenly split on what they think their government’s top spending priority should be in the coming year: 34 percent say the healthcare system, 31 percent say subsidies, and 30 percent say the education system. But those who are food insecure (33 percent) are more likely than their food secure counterparts (27 percent) to want money dedicated to subsidies.

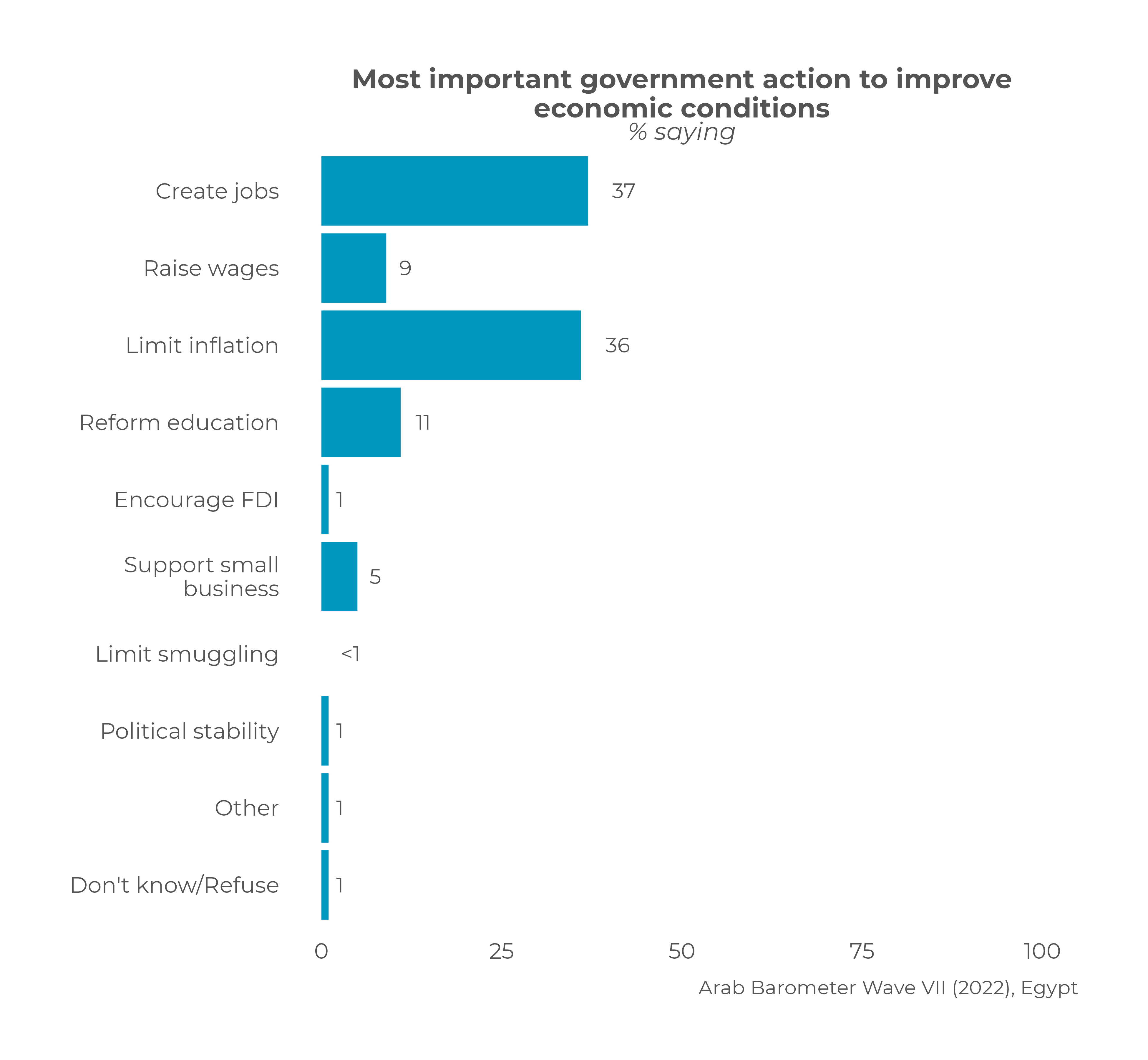

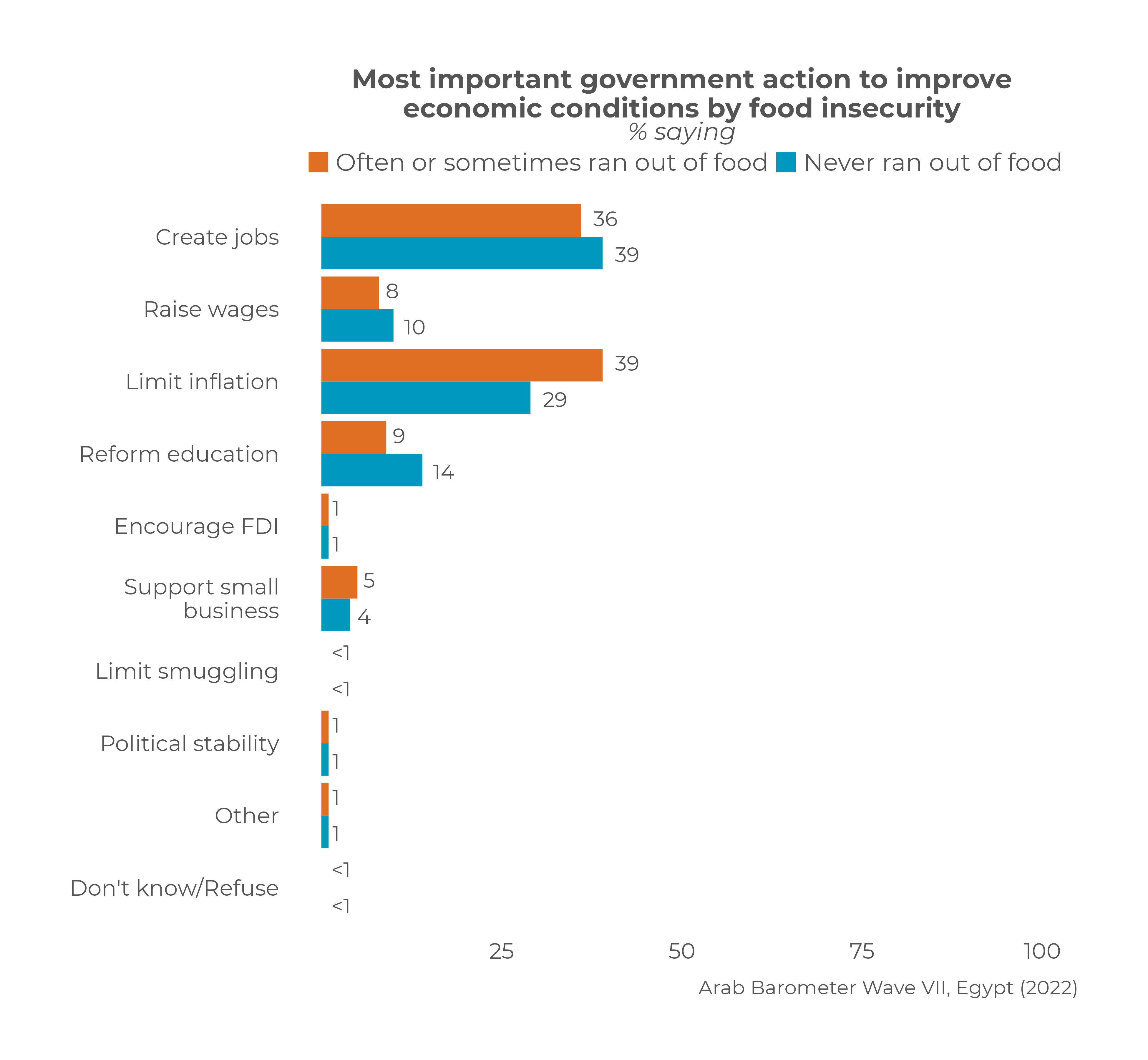

Likewise, citizens are split in desired steps the government should be taking to improve economic conditions: 37 percent of citizens want it to focus on job creation, and 36 percent want it to focus on limiting inflation. While food secure and insecure citizens are nearly evenly split on wanting the government to create new jobs, those who have often or sometimes ran out of food (33 percent) are likelier than those who never had (26 percent) to want the government to focus on limiting inflation.

Yet, spending on subsidies and limiting inflation may prove to be a tall order in the current climate. To be sure, the Egyptian government did start selling discounted bread to those in its bread subsidy program. Still, aysh, or the small loaves on which so many subsist, is not what it used to be: to deal with shortages, bakers have halved the size of loaves. Furthermore, devaluation of the pound has been a demand of IMF and Gulf state financers who placed this as a condition for new loans. The country’s debt has not only doubled in the past decade, but also, repayment of loans constitutes just under half of the FY22-23 budget.

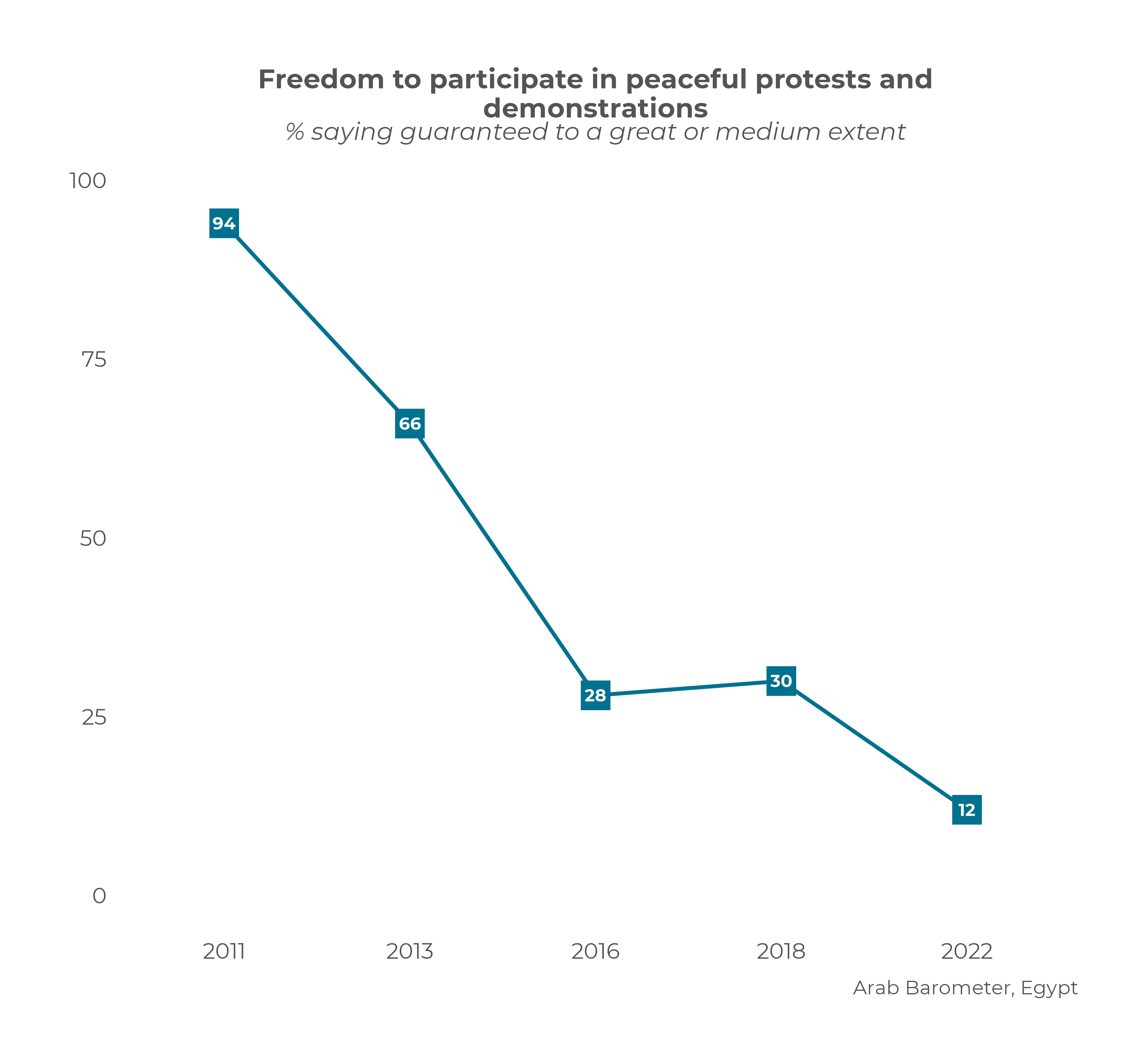

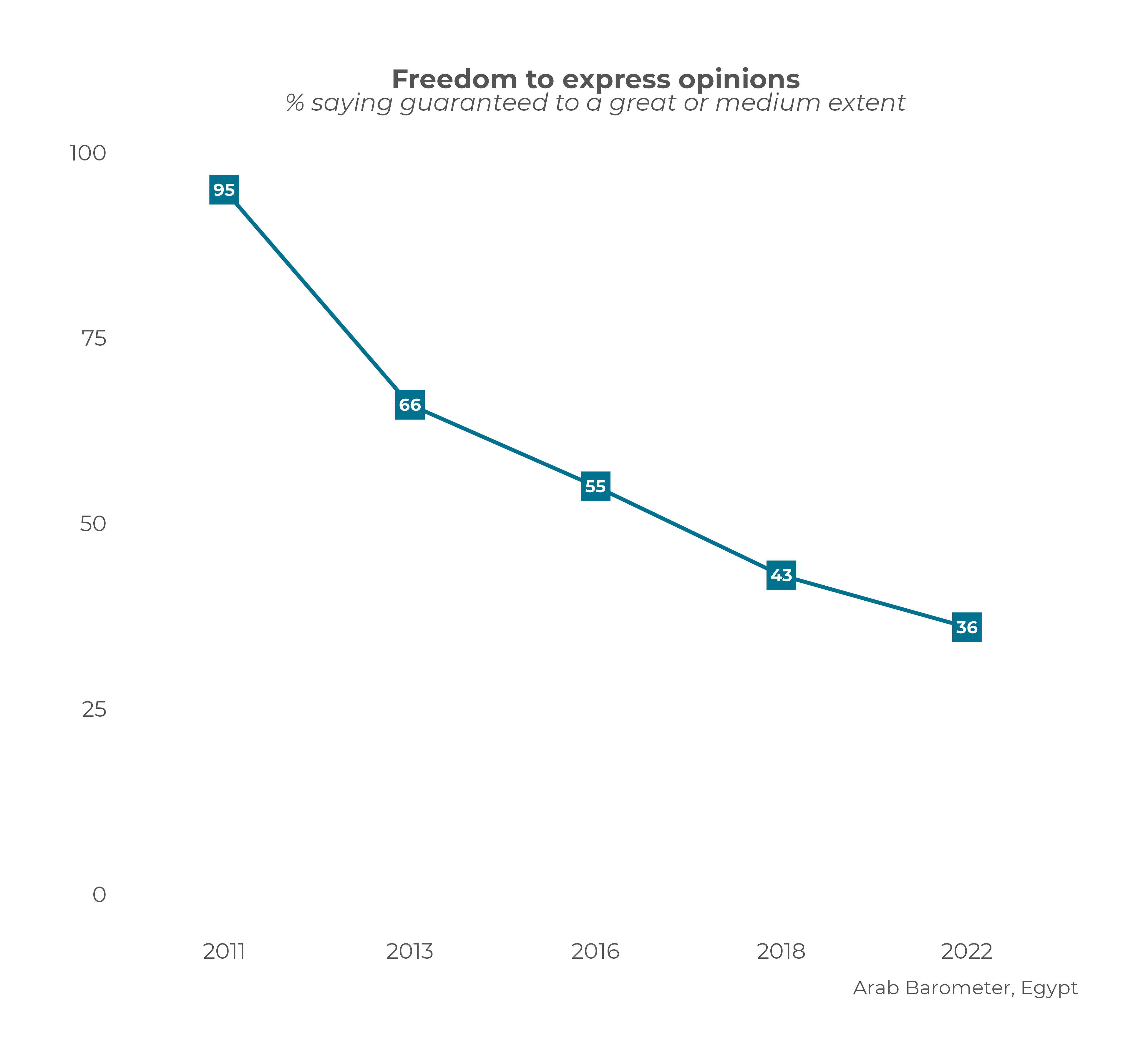

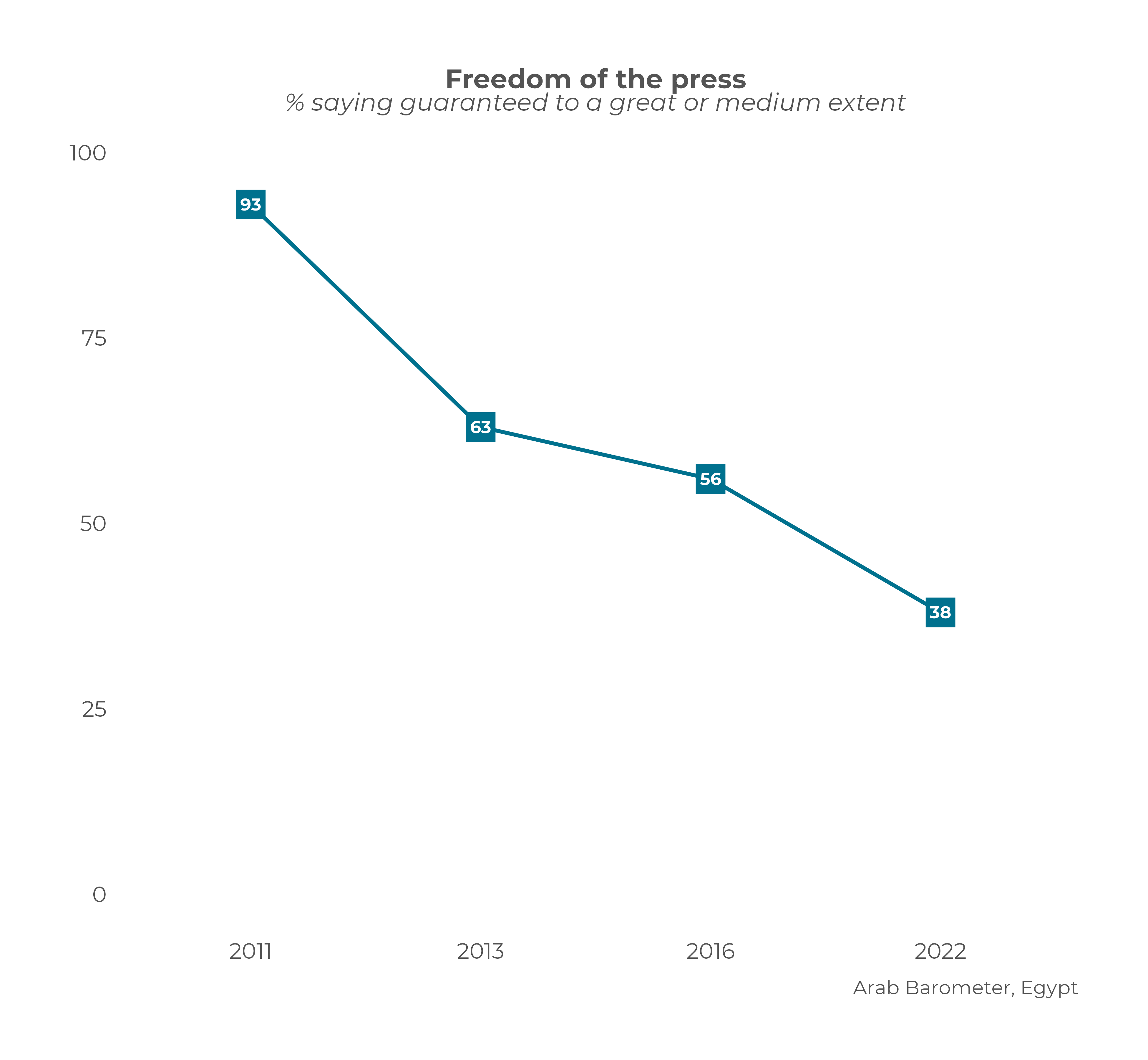

More troublingly still, the Egyptian pound is not the only thing in freefall: Egyptians perceive their rights to be in perilous decline. In the decade since Arab Barometer carried out its surveys in Egypt, citizens’ beliefs that the freedoms of speech, of the press, and of the right to protest are at all-time low. Changes over time in latter freedom are most striking of the three. In 2011, 94 percent of Egypt’s citizens said the right to participate in peaceful protest and demonstration was guaranteed: in 2022, it’s just 12 percent who say the same. While ordinary citizens bear the brunt of the coupling of political and economic stagnation, the prolonged presence of both never bodes well for anyone.