This piece is part of a four-part series published by the Middle East Institute in cooperation with Arab Barometer analyzing the results of the sixth wave of the Arab Barometer surveys.

The latest round of public opinion surveys conducted by Arab Barometer confirms that the deterioration of the economy — or more specifically a continuing collapse in living standards — has been at the forefront of people’s minds in Tunisia. Examining this economic backstory may help explain how and why there was fertile ground for a massive political shift on the scale of President Kais Saied’s July 25 decisions — and the initially exuberant responses to it. They also highlight the oft-neglected relationship between the economy and democracy. If democracy is just about elections — a minimalist approach often applied by political scientists examining Tunisia — then this formulation of democracy has consistently failed to deliver governing officials who are willing or able to address Tunisia’s economic crisis. A different approach to democracy, one that prioritizes not just political equality at the ballot box but some form of economic equality, might more appropriately reflect the democratic aspirations of Tunisians.

The sixth round of the Arab Barometer surveys, carried out between November 2020 and May 2021, covers seven countries — Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon — which is useful for comparative studies. The surveys also build on previous ones from Tunisia, which allows some historical comparisons. There are, of course, limits to an ethnic, linguistic, or identitarian (however “Arab” may be defined) comparative approach, as it may accentuate a perceived exceptional character to Arab countries. One can imagine the broader global trends or geographical convergences and divergences — say inter- or intracontinental ones — that could be studied if such surveys included both North Africa and South Europe, or both North Africa and the rest of Africa, respectively.

Where does Tunisia stand out?

But insofar as the latest round of surveys gives us some basis for comparison, where does Tunisia stand out? Along with the Lebanese, Tunisians, far more than citizens in the other Arab countries surveyed, see economic issues as the most pressing ones. Just over half of Tunisian and 64% of Lebanese respondents pointed to the economic situation as “the most important challenge facing [their] country today,” in a survey conducted in November 2020. For comparison with Tunisia’s neighboring countries, only 28% of Algerians and 19% of Libyans put economic grievances first. Both Tunisia and Lebanon also had the highest percentage of respondents citing corruption as a top issue — 18% and 17% respectively; at the same time, and unlike in any of the other countries surveyed, a majority in both Tunisia and Lebanon said their governments were doing nothing at all or only working a small extent to “crack down on corruption.”

The similarities between Tunisia and Lebanon in terms of popular perception of economic issues do not stop there. Asked how their governments should improve economic conditions, Tunisians and Lebanese again, far more than the other countries surveyed, called for lowering the cost of living (27% and 40% respectively). Yet neither national group have trust in their government to actually do anything, with half of Tunisian and 85% of Lebanese respondents saying they have “no trust at all” in their governments.

This similarity of perceptions among Tunisians and Lebanese with regard to their economic issues is striking when compared to how their economies are described by outside observers. Whereas the World Bank in a June press release warnedthat Lebanon’s economic crisis was one of the “most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-nineteenth century,” its latest press releases on Tunisia stick to positive stories about Bank financing for a “social safety net” and a vaccination program rollout (whether this financing is loans or grants is not specified). To be sure, the World Bank’s overview page of Tunisia, as of its June 21, 2021 update on the website, eventually points to Tunisia experiencing a “sharper decline in economic growth than most of its regional peers;” but the overview begins by highlighting the policy reforms that the Bank has been supporting for years, if not decades: cutting subsidies and abandoning state- owned enterprises.

How can prioritizing cutting subsidies — as the Tunisian government did in June— respond to the widespread economic grievances Tunisians express when they are surveyed? Successive Tunisian governments have carried out reforms in the last decade in line with the neoliberal orthodoxy advocated by Tunisia’s creditors: reductions to subsidies; a new investment code friendly to business and a “start-up” act; a central bank independence law, and a devaluation of the currency as part of liberalization efforts. Yet despite all of these reforms, Tunisia has still seen its debt-to-GDP rise, increasing unemployment, rising inflation rates, and persistent trade deficits that have all had direct or indirect negative effects on ordinary people’s standard of living. With public spending and real wages down, some have also wondered how the state can afford tear gas — which authorities have used excessively in residential neighborhoods — but not oxygen for hospitals.

And while Lebanon is clearly facing an economic crisis with deadly consequences, there are some issues covered by the latest round of Arab Barometer surveys where a higher percentage of Tunisians than Lebanese said they experienced economic misery: in their income not covering their needs, in unemployment, and in the number of unemployed who have given up looking for jobs. A whopping 64% of Tunisians said their net household income did not cover their expenses, slightly lower than 68% in Jordan but higher than 62% in Lebanon. Setting aside the regional comparison lens in favor of the historical one, the surveys also suggest things have been getting worse. A May 2021 survey found that only 6% of Tunisians said the current economic situation was “good” or “very good.” In 2018, that number had been 7%; in 2016: 14%; in 2011: 27%.

Democracy and the economy

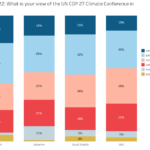

How might these economic grievances be linked to democracy? The surveys also asked Tunisians how essential the provision of basic material necessities to all like food, shelter, and clothing is to democracy. Forty-six percent responded that such material provisions are “absolutely essential” to democracy, and another 28% said they were somewhat essential. This led the researchers at Arab Barometer to conclude that Tunisians “define democracy in terms of economic outcomes.”

So far, electoral, parliamentary democracy has seemingly failed to deliver these economic outcomes. Yet despite this, given a choice of three responses regarding their opinion of democracy, 55% of Tunisians chose the following in a November survey: “Democracy is always preferable to any other kind of government.” Only 24% opted for the choice: “Under some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable,” with another 13% saying the kind of government doesn’t matter for them. Defining the form of Tunisia’s democracy didn’t end with the 2014 constitution; debates continue to this day, and there are indications that the assurance of basic social and economic rights will be integral.

Fadil Aliriza is the founder and editor-in-chief of Meshkal.org, an independent news website in English and Arabic covering Tunisia, and a Non-Resident Scholar with MEI’s North Africa and Sahel Program. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Read original article at MEI