This piece is part of a four-part series published by the Middle East Institute in cooperation with Arab Barometer analyzing the results of the sixth wave of the Arab Barometer surveys.

The Arab Barometer’s survey results for Algeria paint the picture of a population understandably worried about the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impact. In surveys carried out in the country from August 2020 to April 2021, the spread of the virus and the business outlook consistently emerged as the top two challenges ahead, with economic concerns rising to the top position and overtaking the health situation over this period. Because of the spread of the Delta variant, Algiers has been struggling to contain the transmission of the virus. New cases and deaths quickly escalated between July and August 2021, taking the health care system to the brink of collapse.

Before the Delta-induced summer crisis Algerians, while concerned about the virus, seemed fairly confident in their country’s ability to withstand the pandemic. In April 2021 respondents were not particularly worried about their hospitals’ ability to cope. Only 14% of respondents were preoccupied with their health care system, while 43% were apprehensive about the risk of a family member getting ill and 18% were concerned with other citizens not following government recommendations.

Vaccination and public health restrictions

Classified by the IMF in its April 2021 regional economic outlook as a “slow inoculator,” Algeria’s vaccination campaign has been lackluster. In early September, with only 3 million people fully inoculated out of a total population of around 45 million, the government announced the launch of a major vaccination effort with the aim of reaching 70% of Algerians. The authorities were also considering introducing a mandatory vaccination certificate for some categories of individuals.

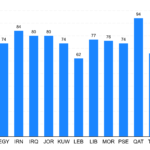

The Arab Barometer survey’s April 2021 results also highlight widespread vaccine hesitancy in the period prior to the Delta outbreak. 45% of respondents considered it very unlikely that they would get a vaccine if it was available for free, while 8% thought it was “somewhat unlikely.” Asked about their preference among available vaccines, Algerians were more confident (34%) in Russian-made jabs than in U.S.-made ones (12%), while 21% rejected all of the available options.

Over the course of 2020 and 2021, the authorities imposed a series of restrictions in various attempts to slow the virus’ pace of transmission. These limitations have often affected freedom of movement and business activity, for example through curfews and mandatory closing times. These measures have disproportionately hit low-wage and informal workers, many of whom have been constrained in their daily activities and have lost at least part of their income. The Arab Barometer study highlights many Algerians’ concern with these policies’ uneven impact. In April 2021, 59% of respondents believed that the health crisis had worse effects on poorer citizens and 55% thought that migrants were particularly impacted.

Economic outlook

In addition to their impact on these vulnerable segments of the population, the pandemic and government restrictions have also impacted the macroeconomic outlook. According to the IMF, Algeria recorded a 4.6% real GDP contraction in 2020. With a breakeven oil price for its budget of $90 and for its current account of $78, it recorded two large fiscal and external deficits of 12.7% and 10.5% of GDP, respectively, as oil prices were well below these fiscal targets. In turn, these shortfalls have caused the exchange rate to steadily fall since March 2020. The cheaper Algerian dinar has translated into a sharp rise in the prices of imported goods, a consequential change for consumers in a country that imports virtually all of the goods that it consumes.

Unsurprisingly, in the April 2021 survey 42% of respondents assessed that the economic situation was “bad,” and 21% thought it was “very bad.” A plurality of Algerians (32%) indicated that the higher cost of living was their biggest COVID-19-related concern and another plurality (22%) considered it their second-biggest worry. Budget constraints also meant that the government has been unable to offer sufficient financial support for the population. Against this backdrop, 90% of respondents said that they received no aid from the government during the COVID-19 crisis, with 20% complaining that they often worried about running out of money to buy food and 18% saying that they sometimes had this worry.

Over the past months, the Algerian government has unveiled several initiatives to try to revive the country’s grim business outlook. In late August it presented an action plan focused on agriculture, renewable energy, pharmaceuticals, and tourism, with the aim of improving business conditions and simplifying rules for investors in these sectors. Other objectives included the goal of improving human development and, in particular, the quality of education and research. However, local media and economists criticized the whole program for being too vague and lacking specific targets. In addition, in early September the presidential administration announced a series of restrictions on imports, in an attempt to contain the current account deficit and reduce pressure on the exchange rate. However, these measures were likely to also create shortages and fuel inflation.

Looking ahead

Even though the current picture is hardly rosy, the Arab Barometer survey shows that, at least as of several months ago, Algerians remained cautiously optimistic about future economic conditions. In April 2021, 23% thought that in the next two to three years conditions would be much better, while another 23% expected the economy to somewhat improve (compared with 19% who thought it would get much worse and 12% who anticipated a slight deterioration). 34% of respondents indicated that the government should prioritize creating more job opportunities, followed by 21% who highlighted reforming education as a concern.

Overall, the survey results confirm that Algerians are worried about the pandemic and its socio-economic impact, particularly in relation to vulnerable categories, such as poorer citizens and migrants, even as they retain some optimism for the future. The study also highlights how in the coming months the biggest challenges for the government are likely to be dealing with vaccine hesitancy, which could hamper any future economic recovery, reviving business activity, creating jobs, and containing inflation.

Riccardo Fabiani is the project director for North Africa at the International Crisis Group. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Read original article at MEI