Background

In the sixth and latest wave of Arab Barometer, we asked 1,000 Lebanese citizens questions related to the Beirut port explosion and Lebanon’s political system. The results suggest that Lebanon’s economic crisis and poverty remain the top concerns of Lebanese citizens rather than the effects of the blast. And, although Lebanese prefer a civil state in theory, they are hesitant to concede and compromise their confessional privileges.

The following blog written by Michael Robbins, PhD sets out some of the main findings.

Taking Lebanon’s Pulse after the Beirut Explosion

Lebanon is a country in crisis on multiple fronts. Amid an ongoing political and financial crisis, the country has also suffered from the global COVID pandemic in 2020. These challenges were compounded by the massive explosion in Beirut’s port on August 4, which led to hundreds of deaths and widespread destruction of homes and businesses in the country’s capital city.

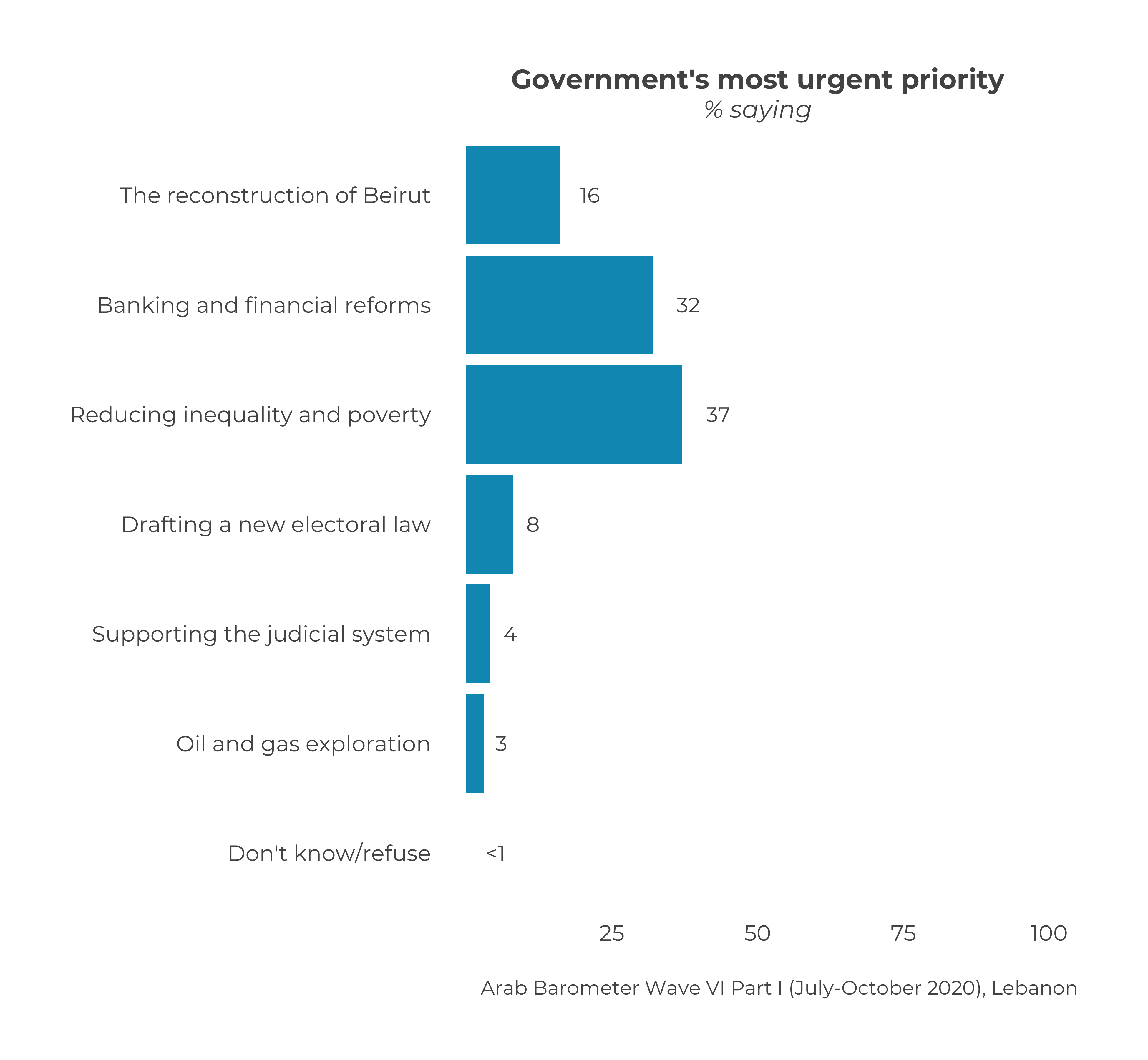

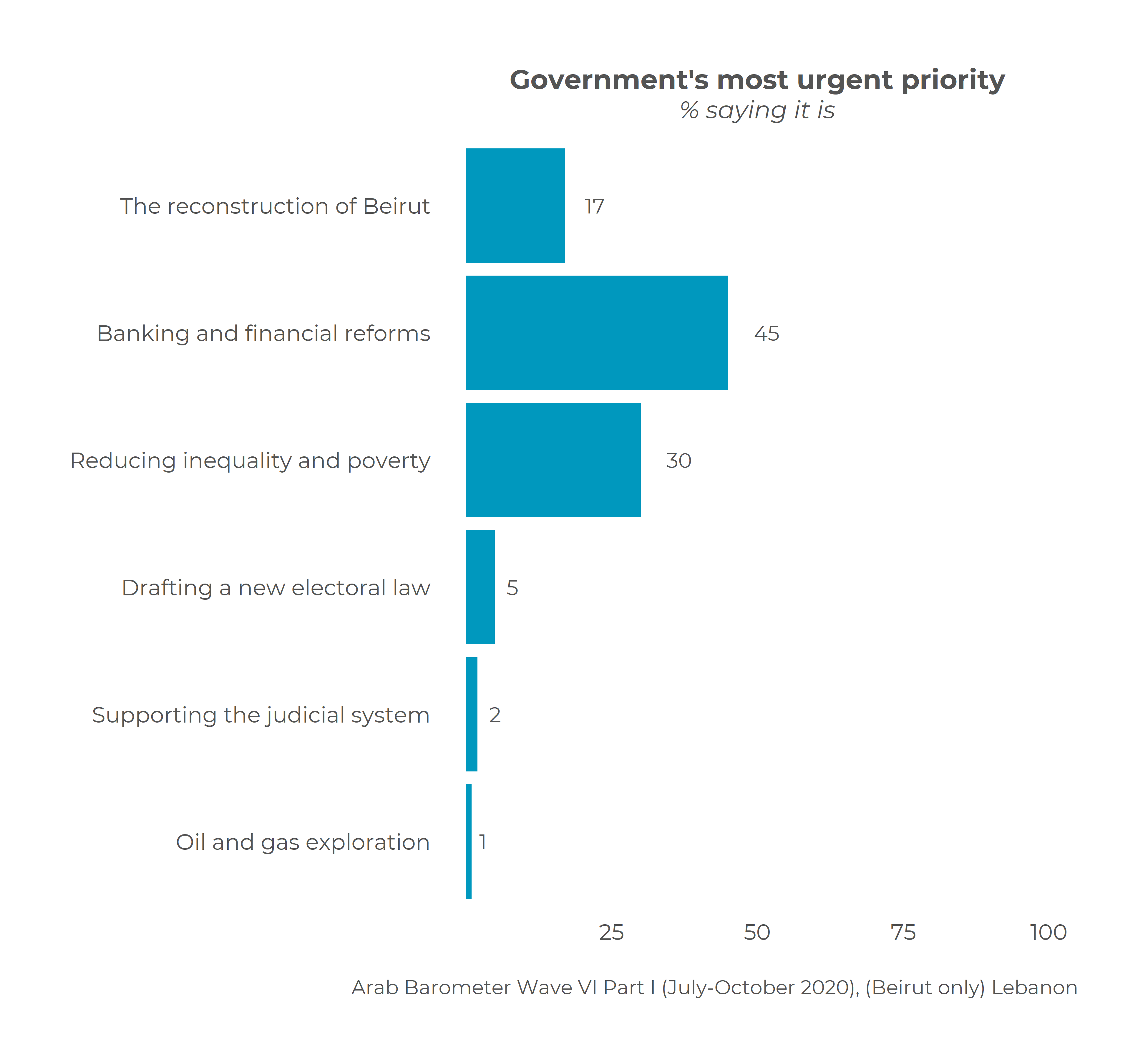

Despite the horror of the Beirut explosion, relatively few Lebanese believe that this is the most pressing issue facing the country. Only 16 percent say the government’s primary focus should be on the reconstruction of Beirut compared with 37 percent who say reducing poverty and 32 percent who say financial reforms. Even in Beirut itself, only one-in-five (19 percent) say the city’s reconstruction is the most pressing issue compared with nearly half (48 percent) who say banking and financial reforms should take priority.

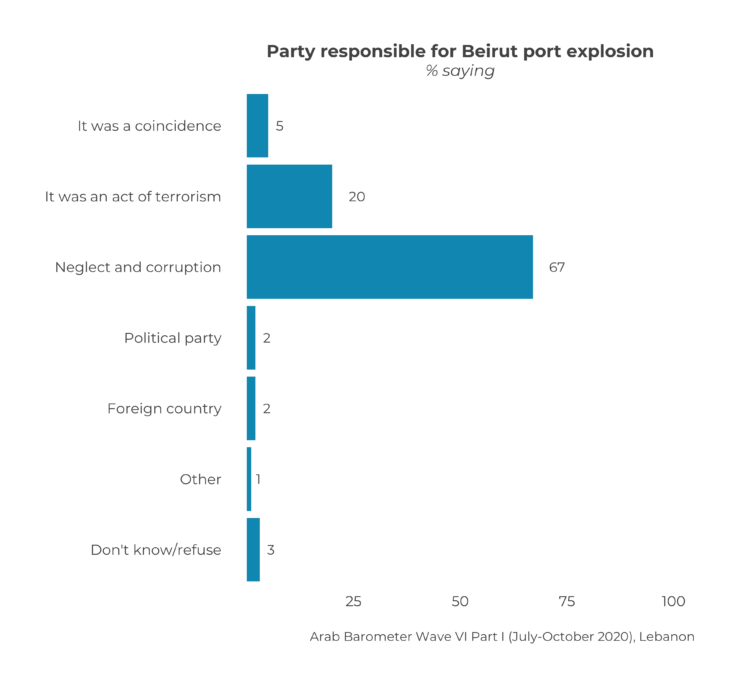

In part, this relative emphasis on issues other than the port explosion may be due to broader concerns related to the Lebanese system. When asked about the primary cause of the port explosion, two-thirds blame neglect and corruption by the governing system. By comparison, just one-in-five blame an act of terrorism while five percent or fewer say it was a chance occurrence, or the act of a domestic or foreign actor.

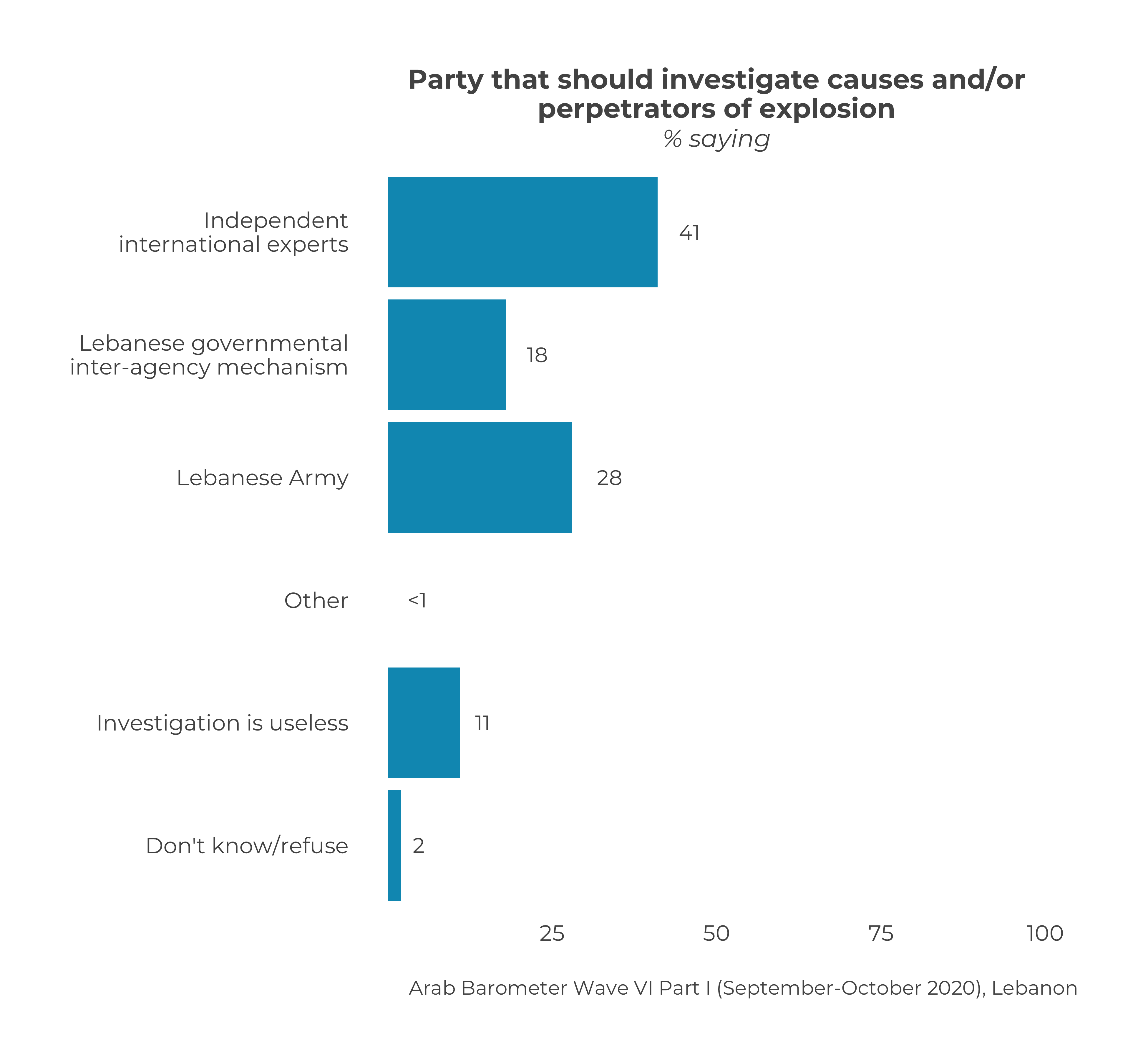

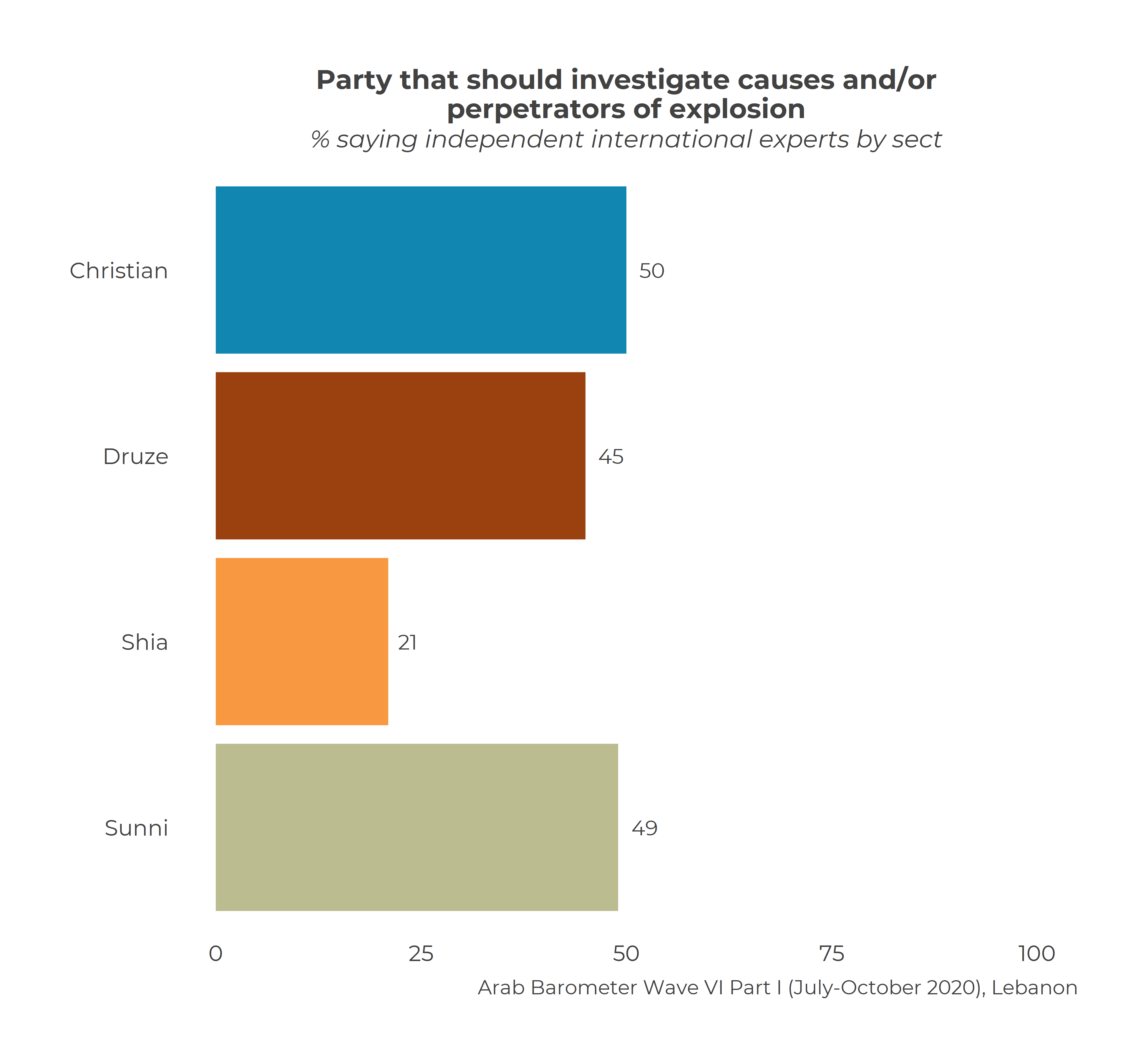

In terms of understanding the full cause of the explosion, Lebanese are inclined to turn to independent international experts. Four-in-ten (41 percent) believe this would be the best choice to investigate the underlying causes, compared with 28 percent who say the Lebanese Army and 18 percent who say it should be Lebanese parties. Additionally, one-in-ten (11 percent) say the investigation would simply be useless. Notably, there are dramatic differences by sectarian identity. Only 21 percent of Shias favor independent international experts, perhaps due in part to the fact the port area is largely controlled by Hezbollah. Meanwhile, over half of Christians, Sunnis and Druze favor independent international experts.

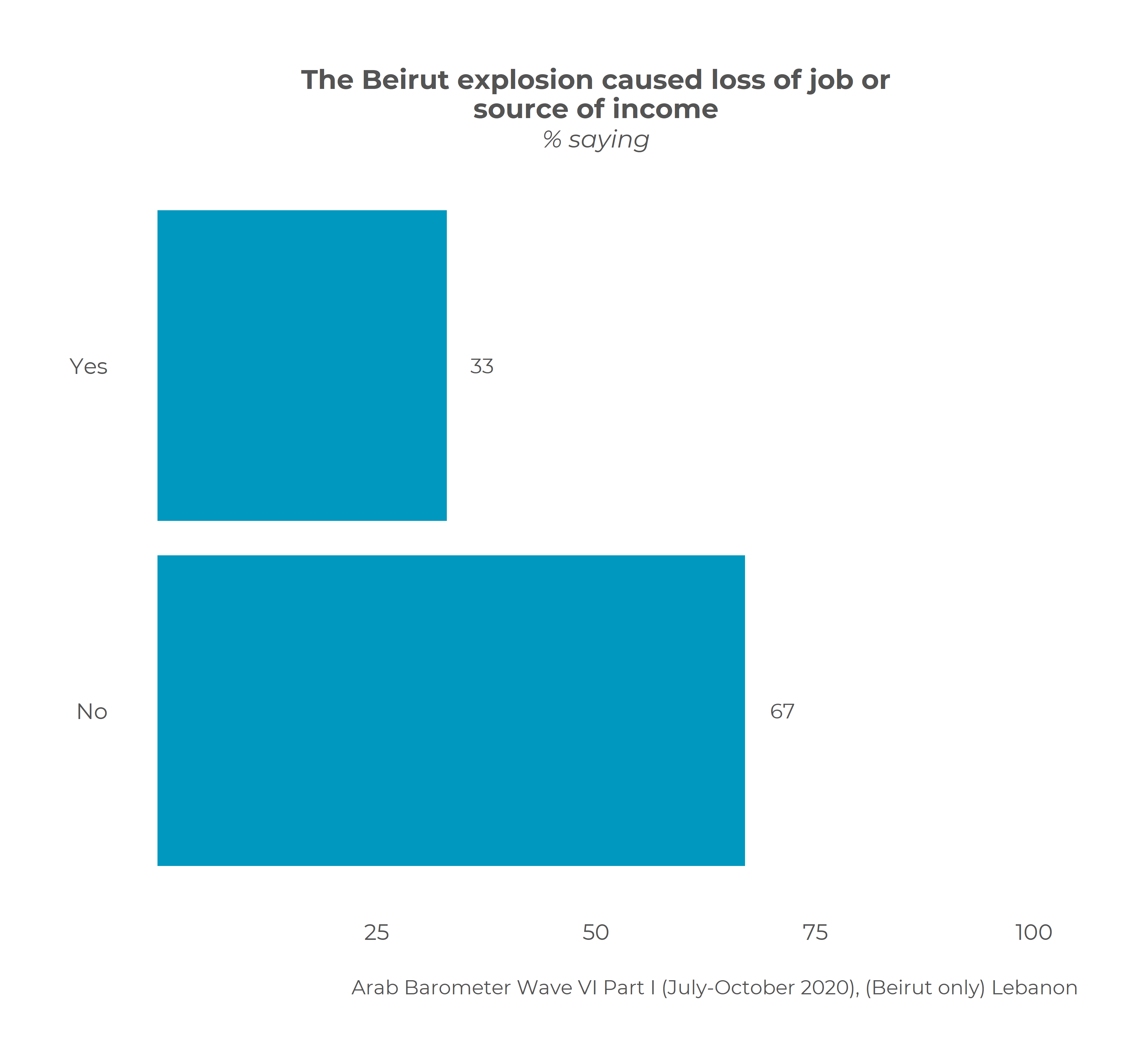

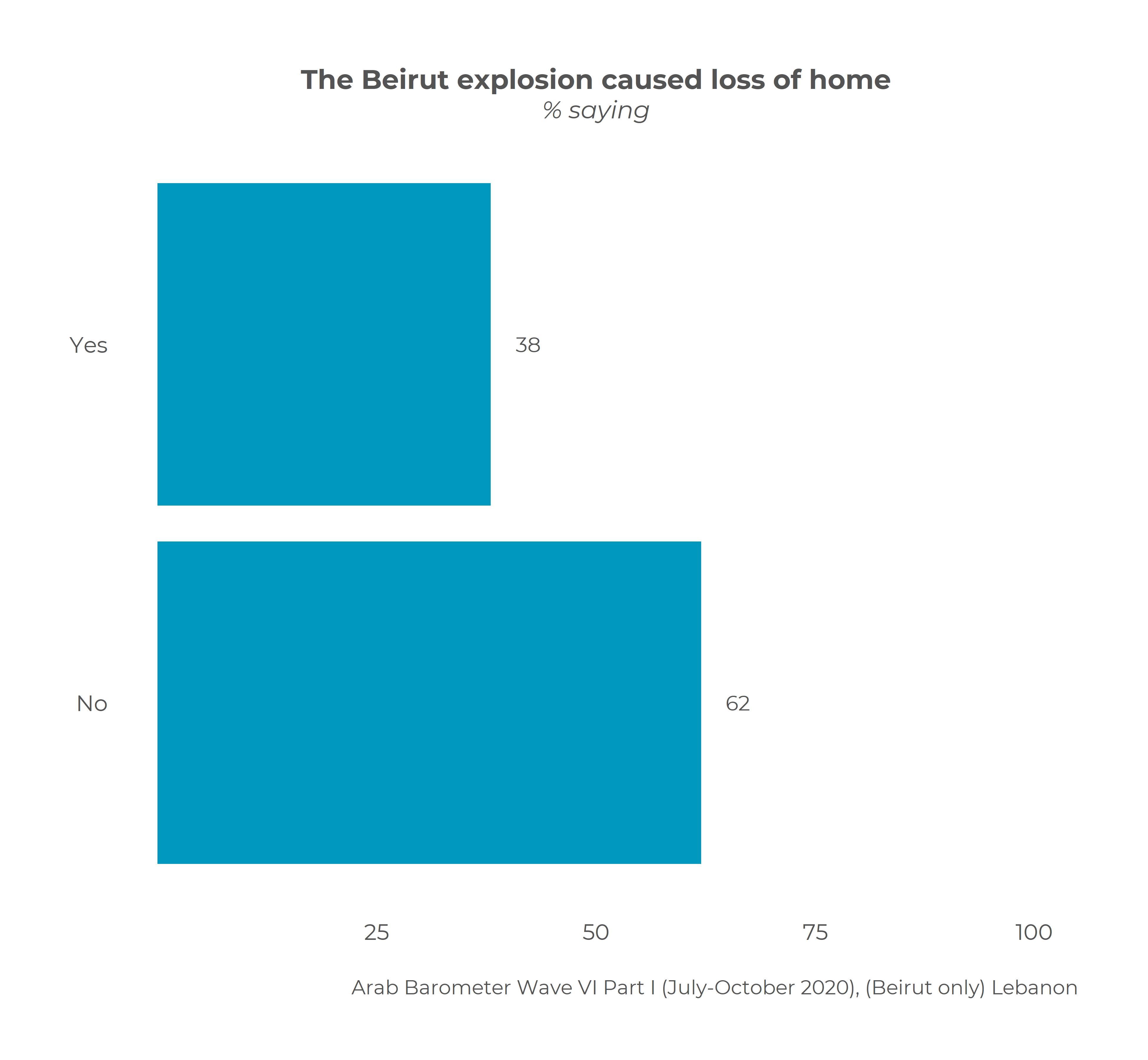

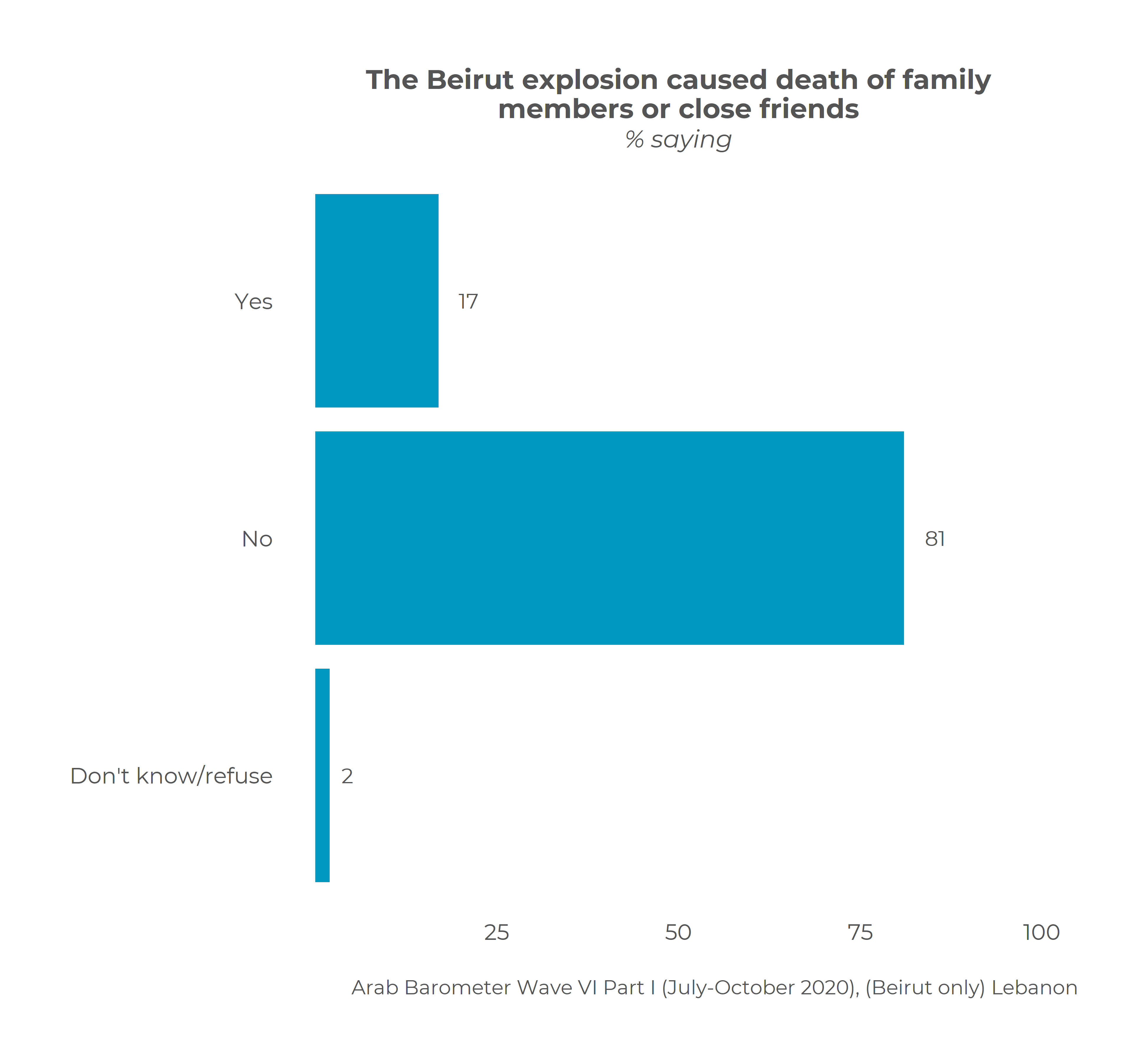

Unsurprisingly, the main effects of the explosion are confined to Beirut. Overall, fewer than one-in-ten Lebanese say they lost their jobs, their homes, or a family member or close friend in the explosion. However, the level of devastation among Beirutis is far higher. Fully 40 percent say they lost their home, a third (34 percent) lost their job in the aftermath, while 15 percent lost a family member or close friend.

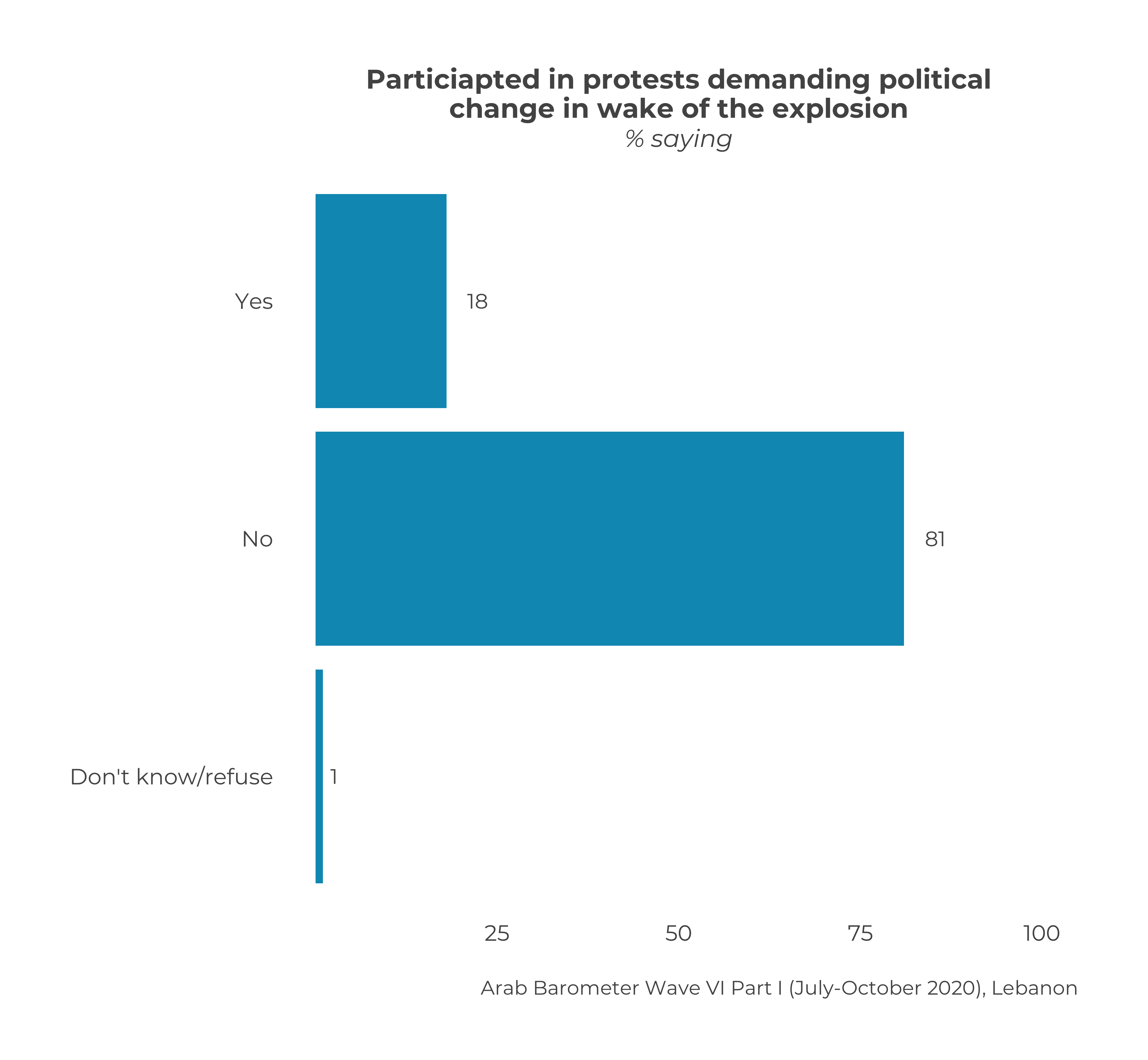

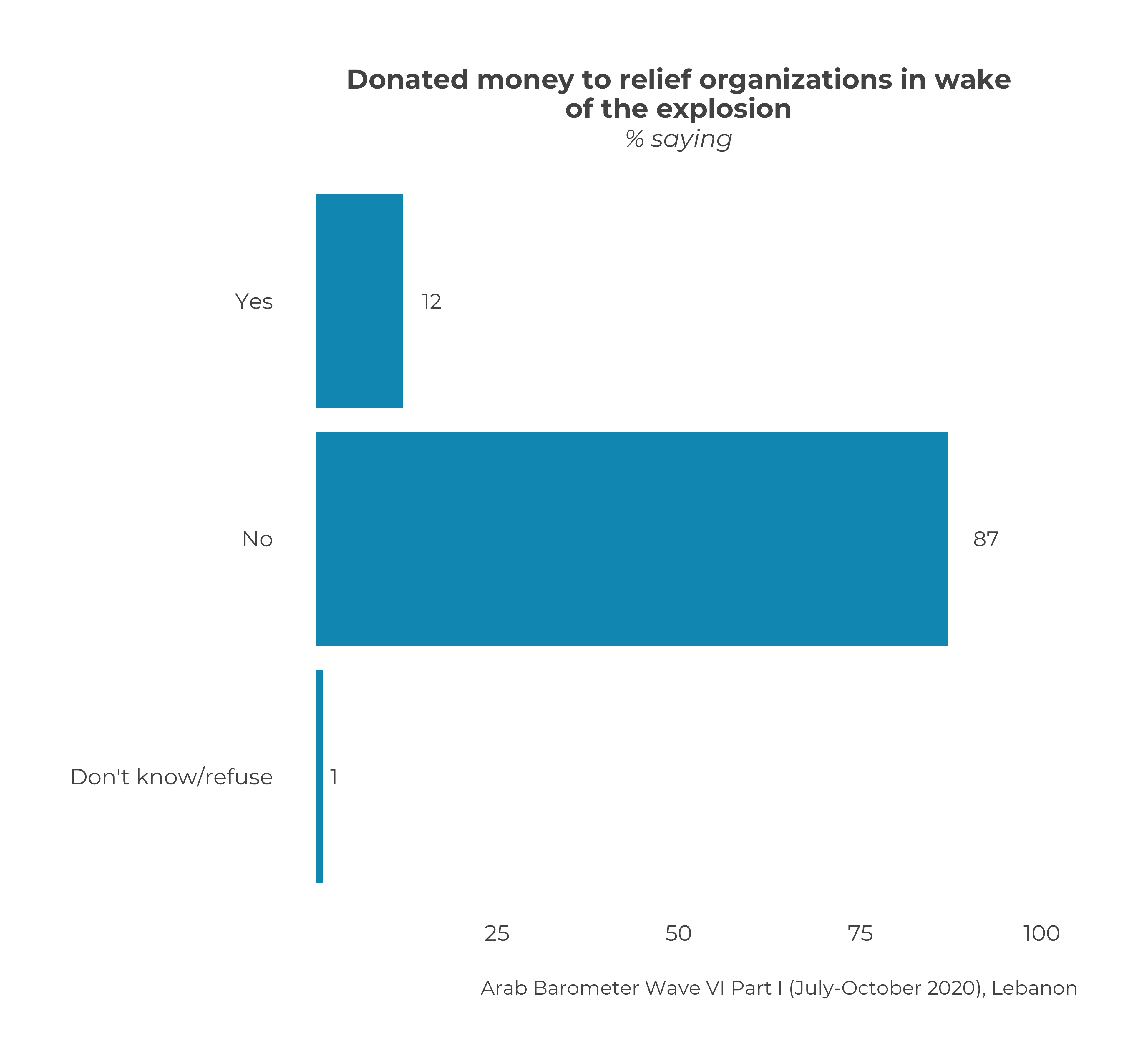

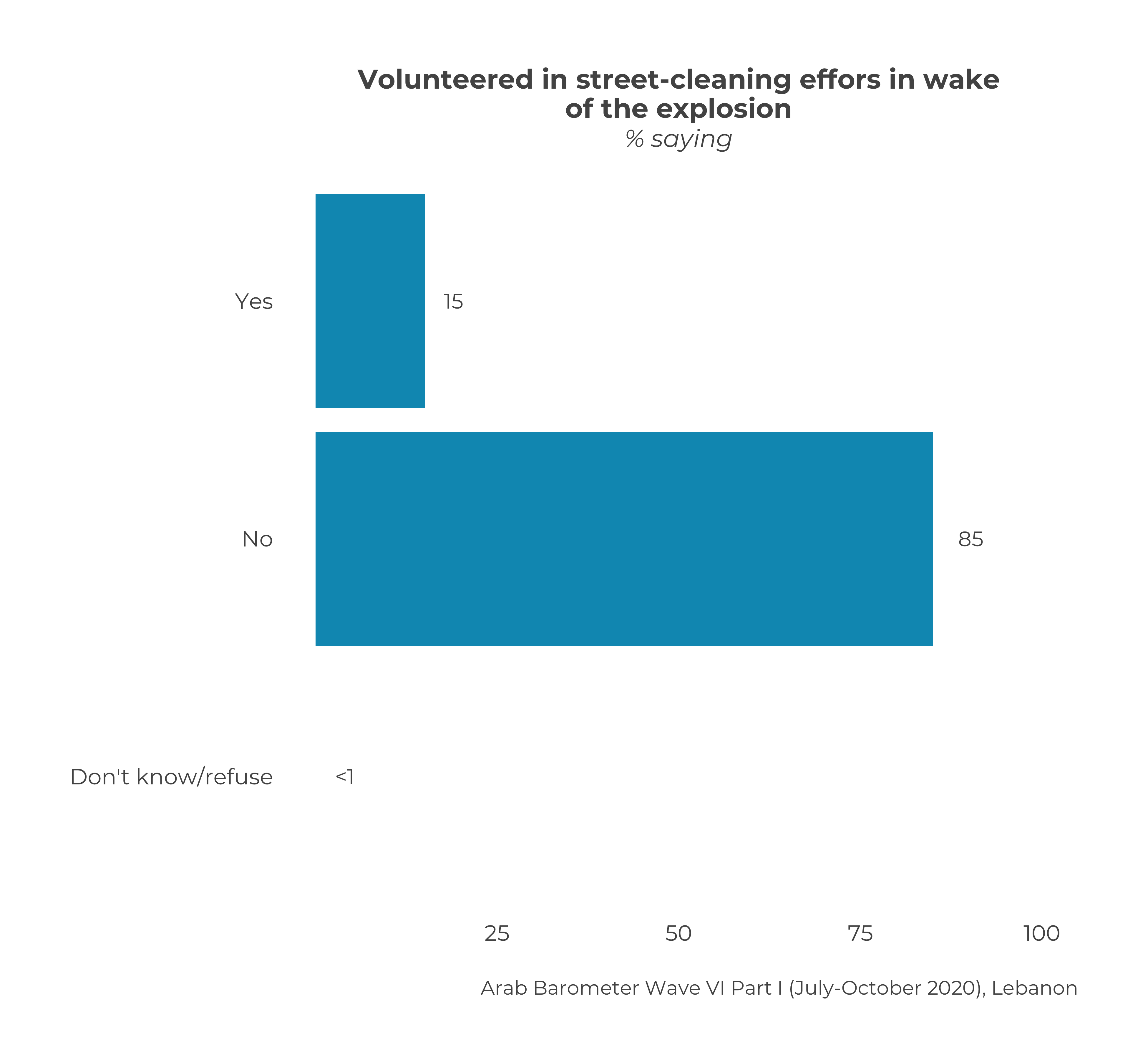

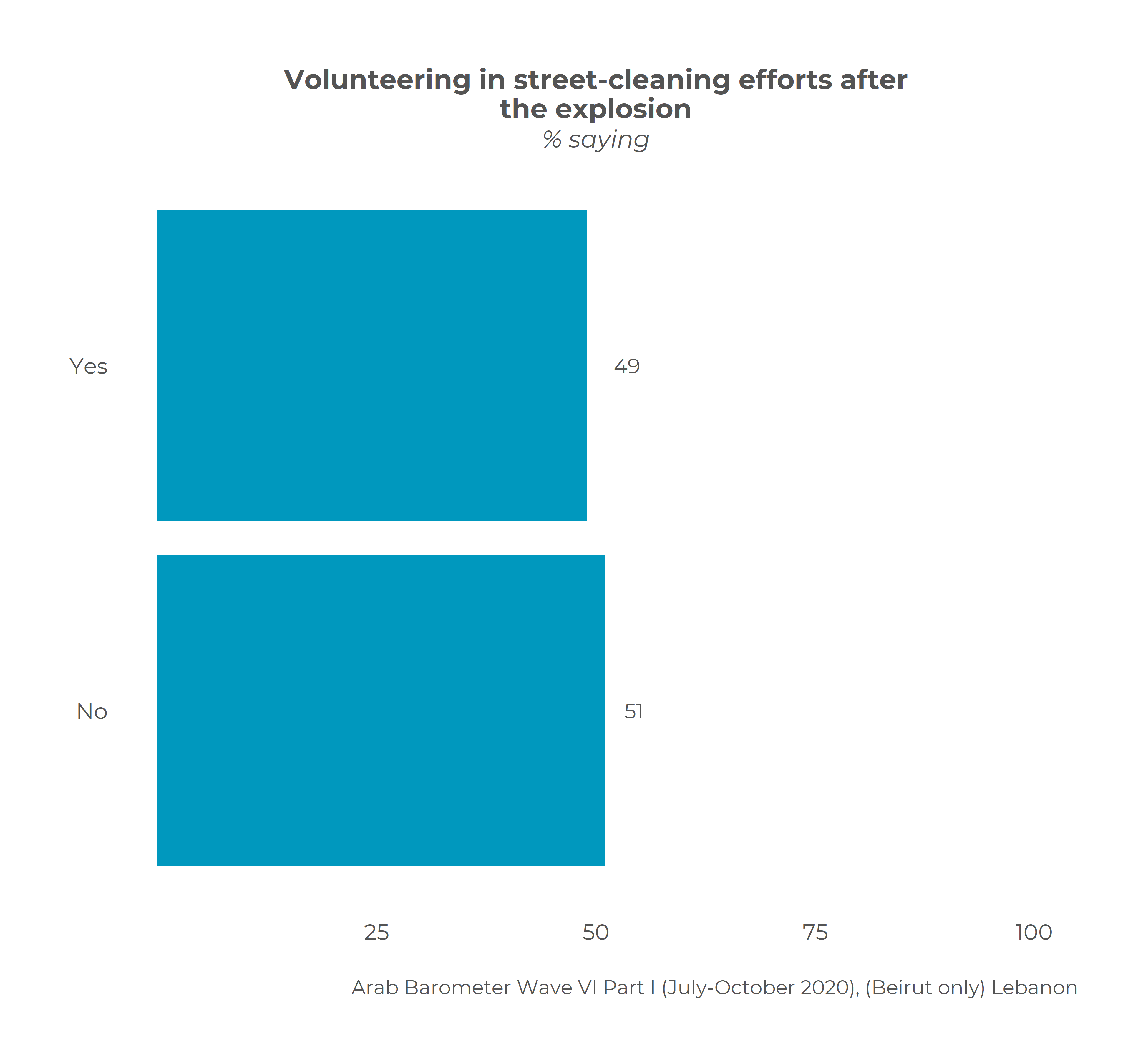

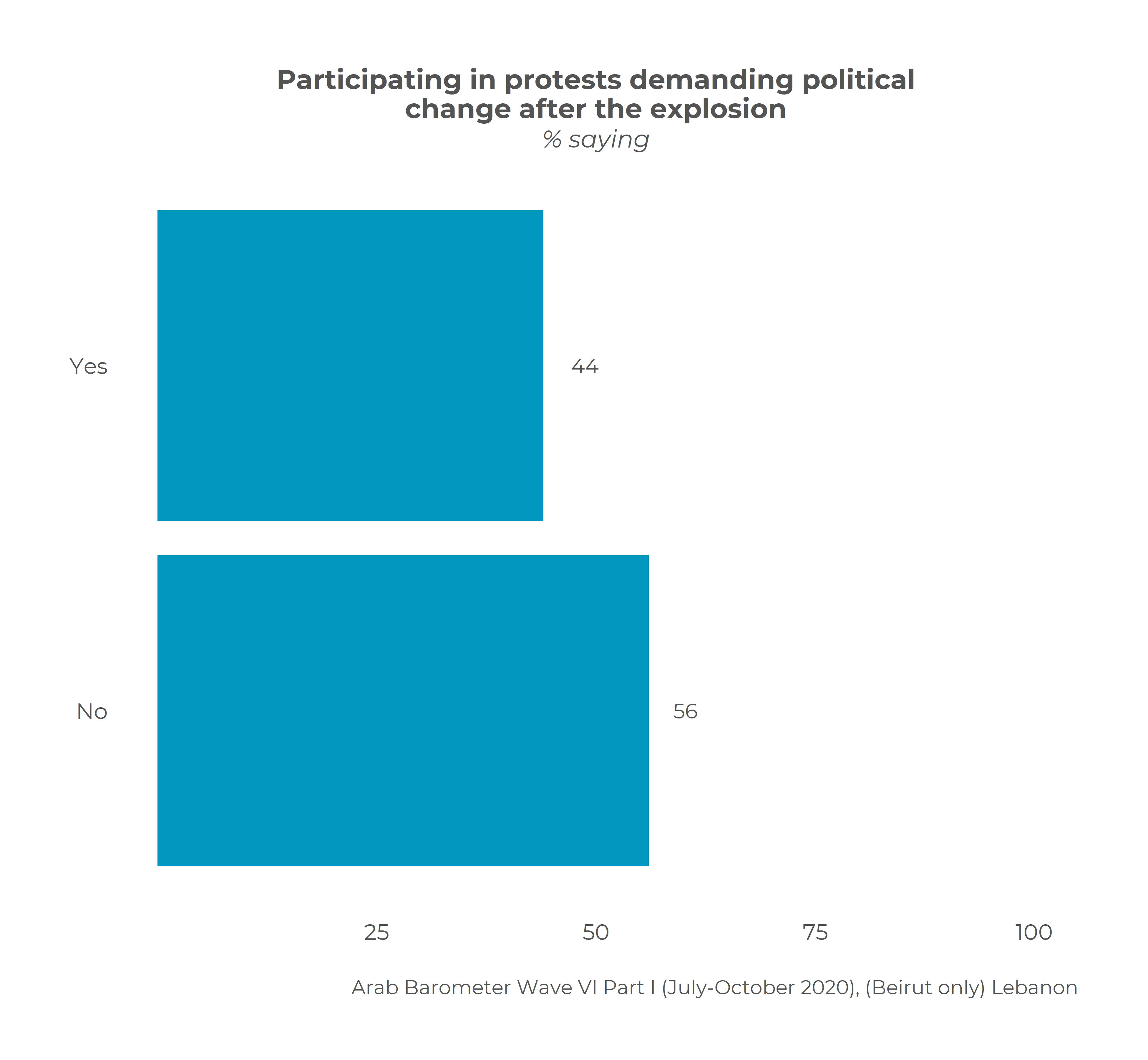

In response to the Beirut explosion, many Lebanese decided to take action. Across the country, nearly one-in-five (18 percent) choose to take part in a demonstration demanding political change, 15 percent volunteered to help clean up efforts, and 12 percent donated funds to victims of the blast. In Beirut itself, fully half (53 percent) of citizens volunteered to take part in cleanup efforts while 49 percent took to the streets to demand political change.

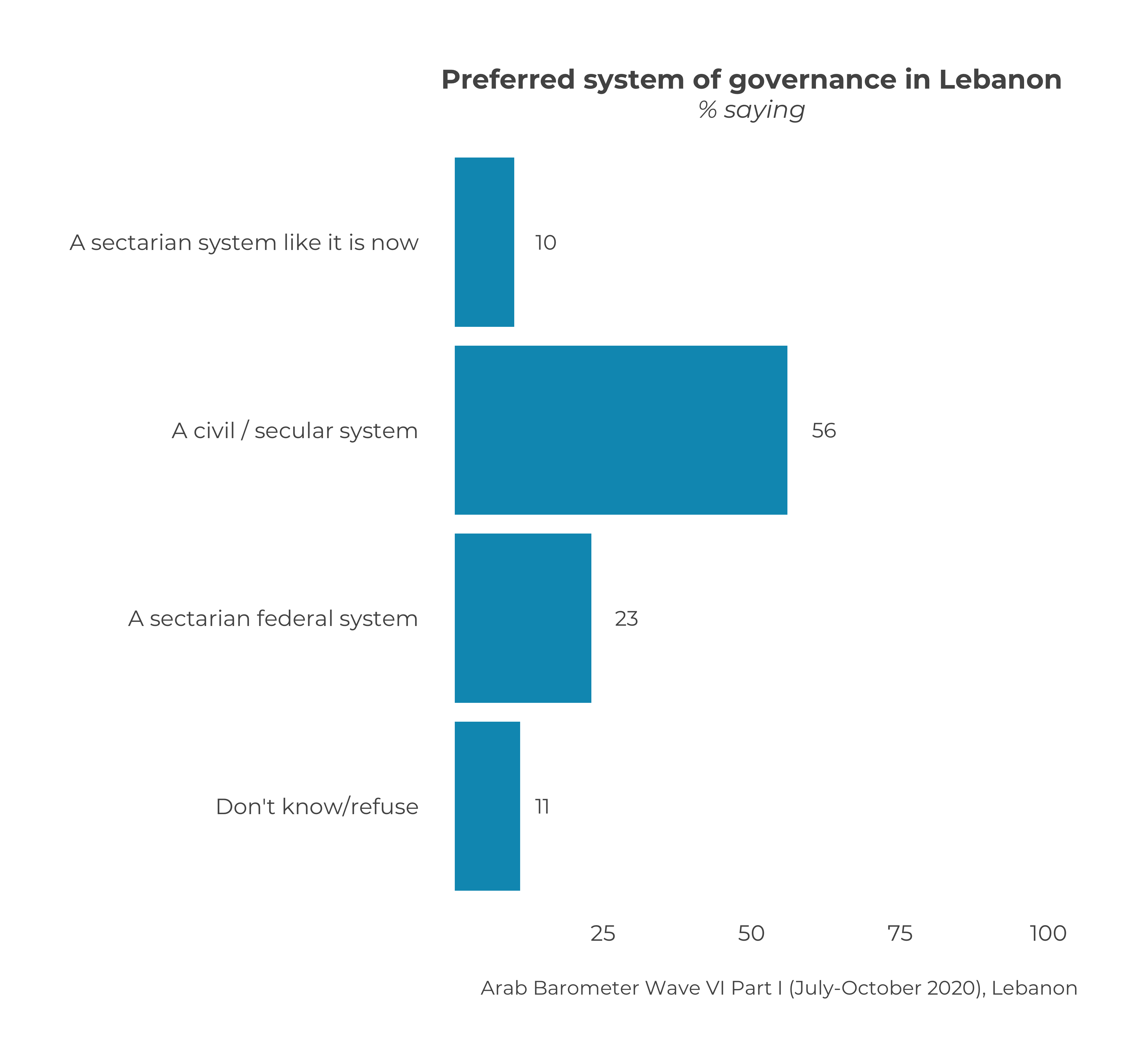

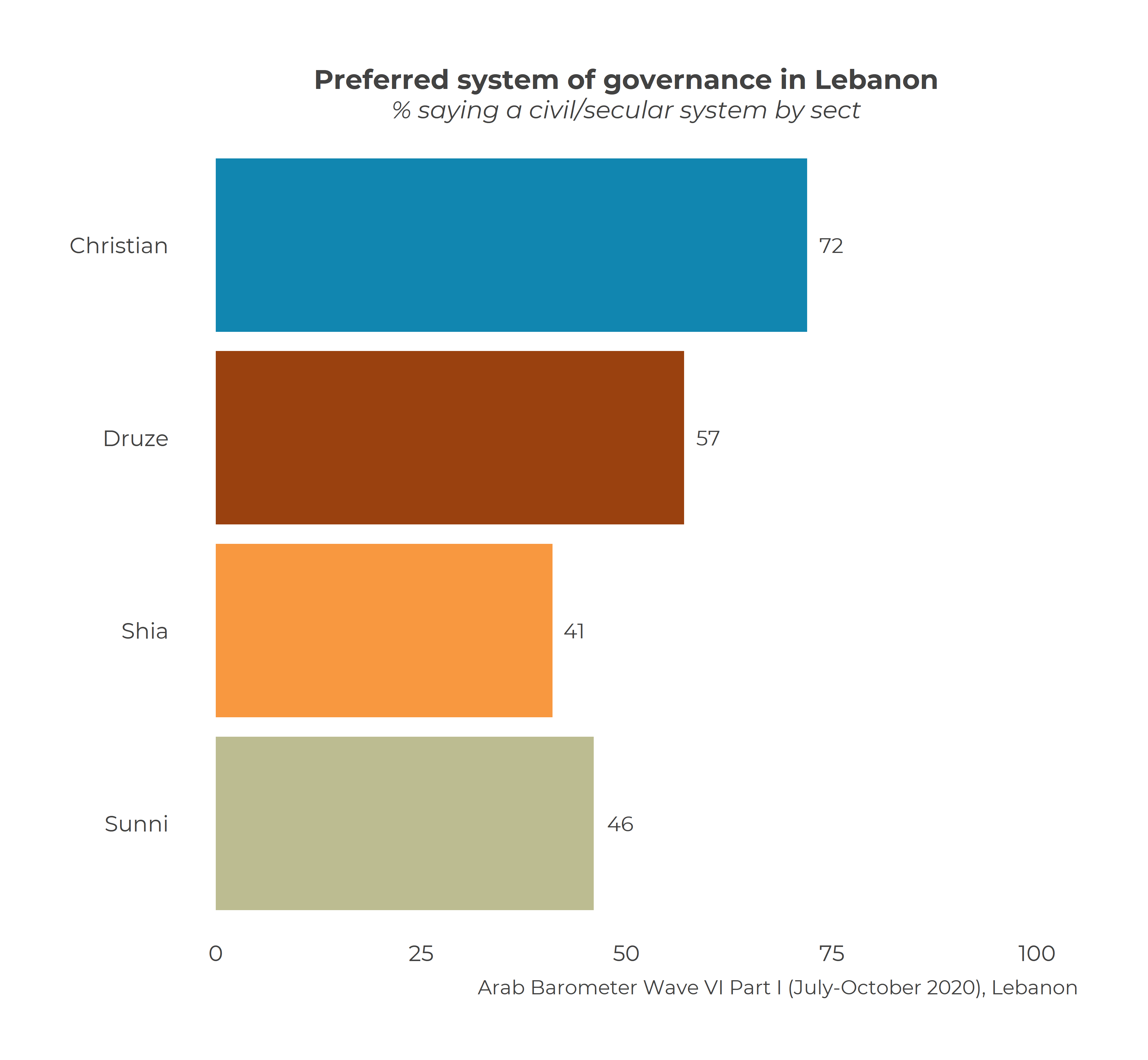

It is clear that Lebanese, and Beirutis in particular, demand change to prevent such an outcome from happening again. However, it remains an open question the type of change that is desired. One major question is the role that sect should play in the political system. When asked, only one-in-ten Lebanese prefer the sectarian system that is currently in place. Instead, a slight majority (56 percent) say they prefer a civil or secular political system while 23 percent want a federal system that preserves a role for the country’s different sects. Notably, Lebanon’s Christians are the most supportive of a secular civil state (72 percent), compared with fewer than half of Sunnis and Shias, respectively.

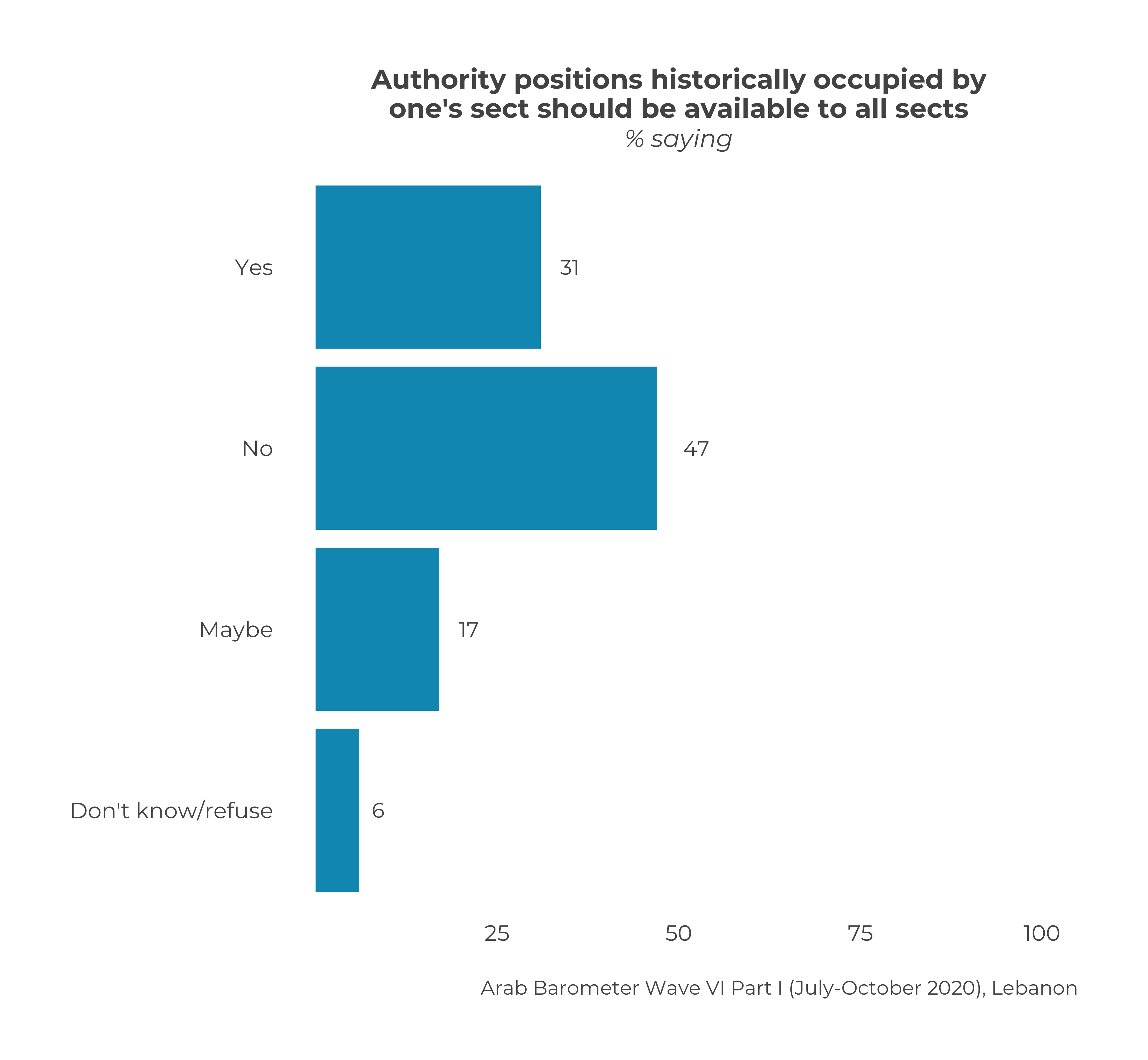

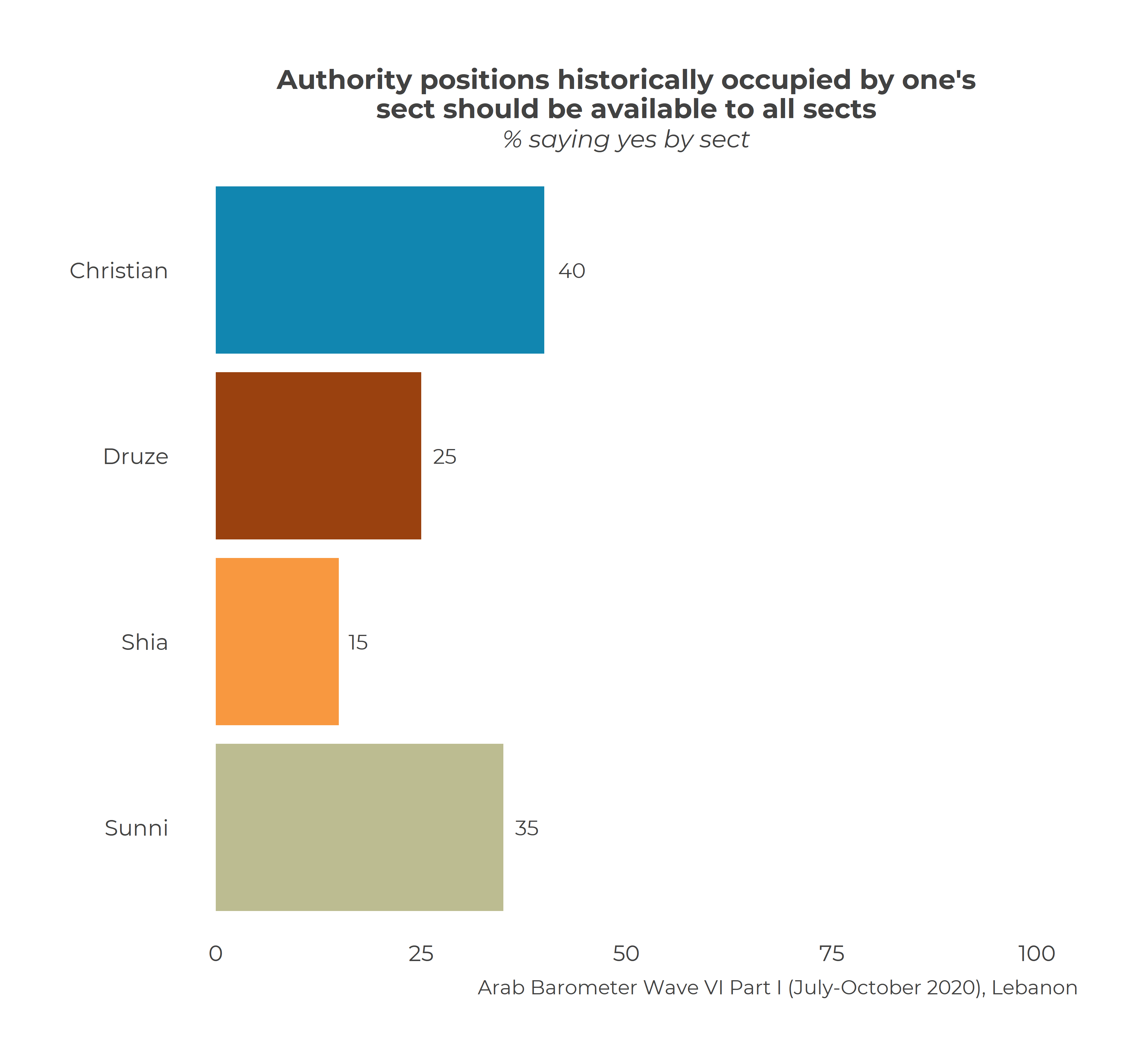

Yet, while a non-sectarian state may be seen as a good system, Lebanese remain worried about losing certain benefits from the current system. When asked if they would be willing to give up political positions that have been historically occupied by members of their sect, nearly half (47 percent) of Lebanese say no. Just 31 percent say yes while 23 percent say maybe or they are unsure. Shias are particularly cautious about giving up their enshrined positions, with 59 percent saying no, although no is the plurality or majority for all major sectarian groups.

In sum, the results of this survey make clear that the port explosion is viewed as a failure of the existing political system in Lebanon. Given its myriad other failures in recent years, Lebanese are demanding change with significant percentages taking to the streets calling for reform. Although a new social compact is desired with most favoring a system that deemphasizes sectarian identities, there remains concern about losing the established privileges of the existing system. Although reform is desperately wanted and needed, it appears there is not a vision that would be acceptable to all Lebanese. Without such a consensus, it is likely that the current paralysis will continue.