Many entities have long suggested that the private sector is the key to economic transformation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) – including foreign governments, international agencies, and economic scholars. Even before the uprisings of 2011, they argued that the private sector has a crucial role to play in reconstructing the strained (if not broken) social contracts of the MENA region. Different theories were put forward for the role that the private sector has historically played and ought to play in the future. Some scholars claim that the absence of a true private sector precipitated the Arab Spring, distinguishing between crony capitalism and independent private enterprise. Others have called out the MENA private sector as being responsible for its own poor reputation, having had non-transparent relationships with government and for pursuing only partial liberalization. Despite these differences, there is a broader agreement among academic and policy commentators that the rentier system, which has pervaded most MENA countries and made the state the center of economic activity, is all but dead and that the private sector must be the economic engine in the future of the MENA region.

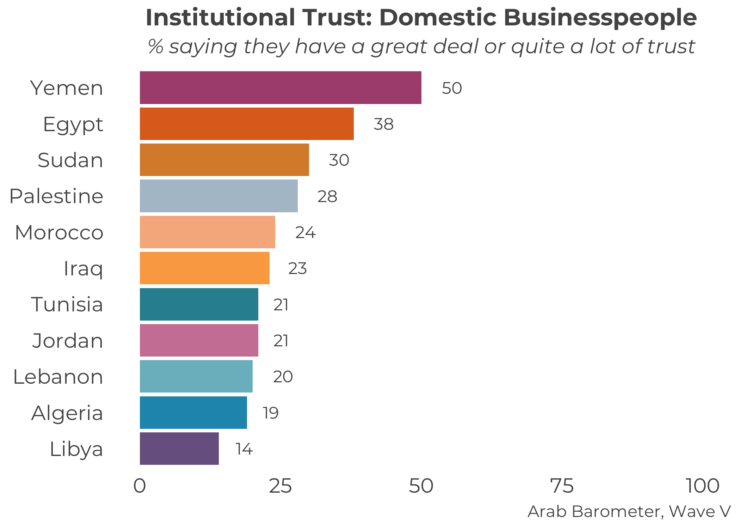

As I have written previously about trust in public institutions, be they representative or executive, I thought it would be fruitful to bring in private institutions to the discussion. According to Arab Barometer Wave 5 data, about a quarter of all respondents (26 percent) trust domestic businesspeople, representing a small minority of respondents. Citizens are most likely to trust businesspeople in Yemen (50 percent) and least likely to do so in Libya (14 percent). However, levels of trust are relatively low across all surveyed countries: 38 percent in Egypt, 30 percent in Sudan, 28 percent in Palestine, 24 percent in Morocco, 23 percent in Iraq, 21 percent in Jordan and Tunisia, 20 percent in Lebanon, and 19 percent in Algeria.

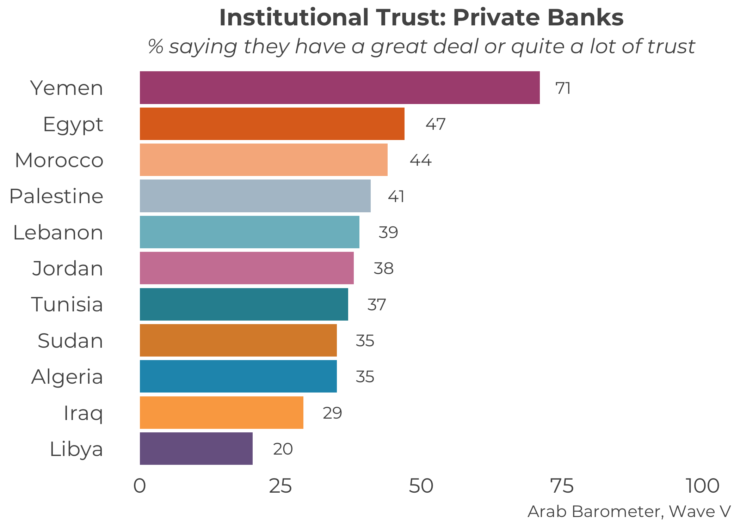

Levels of trust are higher overall for key private institutions. For example, on average 40 percent citizens across MENA trust private banks. Only in Yemen (71 percent) does a majority trust private banks, whereas minorities trust them in the remaining countries: 47 percent in Egypt, 44 percent in Morocco, 41 percent in Palestine, 39 percent in Lebanon, 38 percent in Jordan, 37 percent in Tunisia, 35 percent in Algeria and Sudan, 29 percent in Iraq, and 20 percent in Libya.

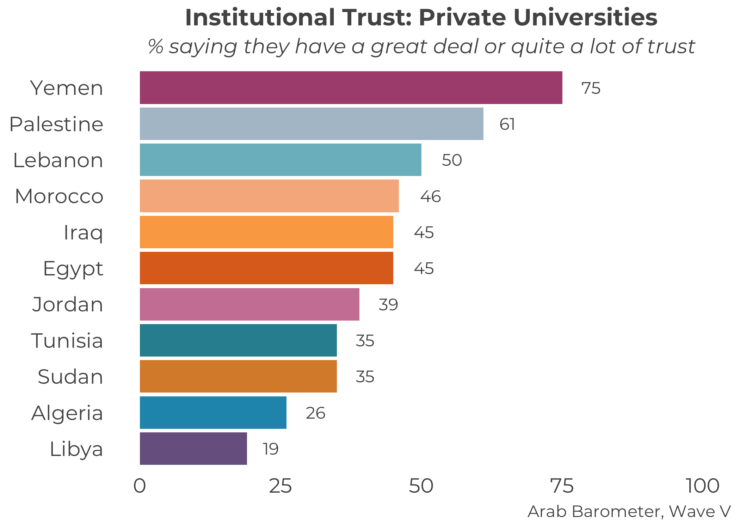

In other sectors in which private institutions are active and visible, such as education and healthcare, levels of trust are higher. On average, 44 percent of citizens in MENA trust private universities, including majorities in Yemen (75 percent) and Palestine (61 percent). Elsewhere, the figures ranged from 50 percent in Lebanon to 46 percent in Morocco, 45 percent in Iraq and Egypt, 39 percent in Jordan, 35 percent in Tunisia and Sudan, 26 percent in Algeria, and 19 percent in Libya.

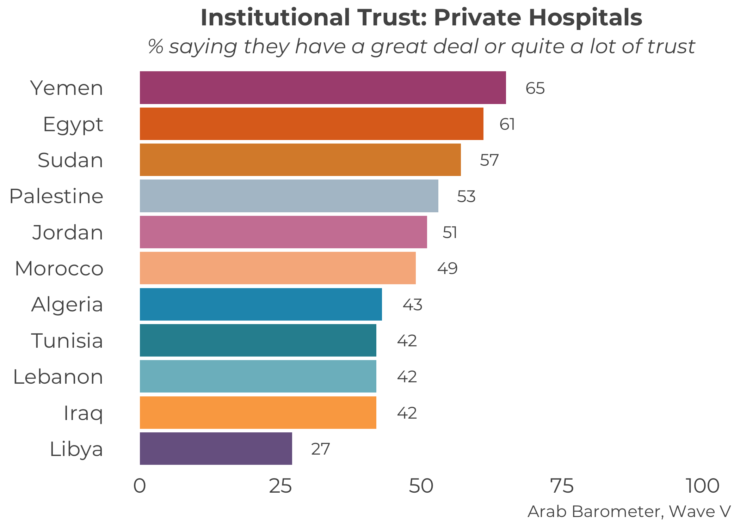

Levels of trust in private hospitals are the highest among the types of private institutions included in the survey. Overall, 48 percent in MENA trust private hospitals, including majorities in Yemen (65 percent), Egypt (61 percent), Sudan (57 percent), Palestine (53 percent) and Jordan (51 percent). Meanwhile, substantial minorities say the same in the remaining countries, ranging from 49 percent in Morocco, to 43 percent in Algeria, 42 percent in Lebanon, Tunisia and Iraq, respectively, and finally 26 percent in Libya.

As such, perhaps the first point of departure should be to differentiate between private sector institutions according to the industry in which they are active. The survey results reveal that the business community and financial sector enjoy lower levels of trust than private healthcare and education institutions. Thus, when scholars speak of lower trust in the private sector, they need to specify which private sectors institutions they are examining.

Existing accounts can help in dissecting the low trust in the business community. In much of the MENA region, businesspeople are viewed as crony capitalists who are non-transparent, seek quick gains, and invest little in their communities – whether through training effective cadres or through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs. Indeed, as Ishac Diwan and Mustapha Nabli have argued, perceptions of corruption in business mirror perceptions of corruption overall. At the same time, Diwan and Nabli argue for the analytical separation between businesspeople and financial institutions, as trust levels in both are weakly correlated. The Arab Barometer survey results, in part, support this finding given that trust in private financial institutions are uniformly higher across the MENA region.

Additional research is needed to understand the basis for higher trust in private healthcare and education institutions. Recent evidence from Jordan suggests that, while the citizenry may prefer going to these private institutions, the issue of affordability remains an important barrier. Many Jordanian families are in fact being pushed out of the market for private education and driven to a reeling public education whose primary workforce has most recently been under state attack. At the same time, the recent experience in dealing with COVID-19 provides an opportunity to critically evaluate the public health infrastructure and the ability of hospitals (both private and public) to deal with the pandemic. As in other trust metrics, it is difficult to generalize across the entire region, but these results make clear that levels of trust in the private sector vary across sectors. Scholars of the MENA, foreign governments, and international agencies would be advised to consider these differences as they promote economic liberalization in the region.