As the world faces COVID-19, public trust is crucial to countries effectively dealing with the pandemic. Already, the swift action of leaders in Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, and New Zealand has been praised. This swift action was enabled and reinforced by citizens trusting government responses to the disease and buying into the isolation measures necessary to slow its spread.

On the contrary, the responses of countries facing the most cases of COVID-19 were hindered by mixed messages from government figures that eroded public trust. In the United States, which tops the world with its confirmed cases and deaths, President Trump’s spread of misinformation, from hailing the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment to suggesting injections of disinfectant could kill the virus, contributed to confusion about the disease and undermined efforts to fight it. Brazilian President Bolsonaro dismissed COVID-19 as a “little flu” and discouraged Brazilians from taking it seriously. His messages eroded public trust in the government as Brazil rose to have the world’s second highest death toll.

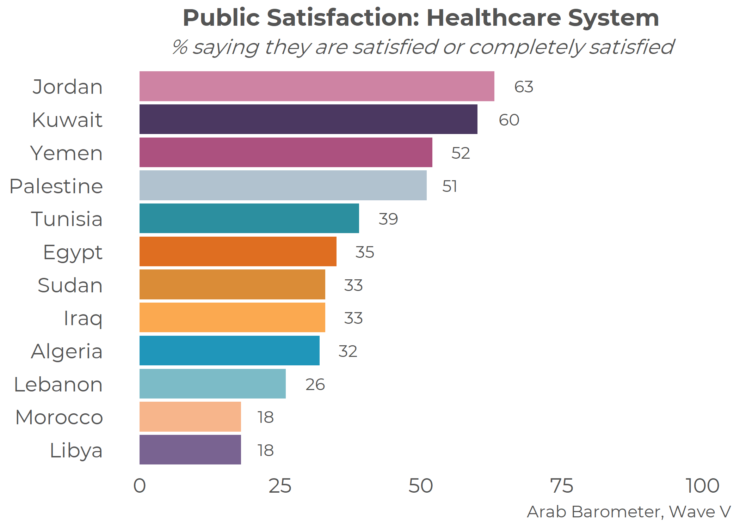

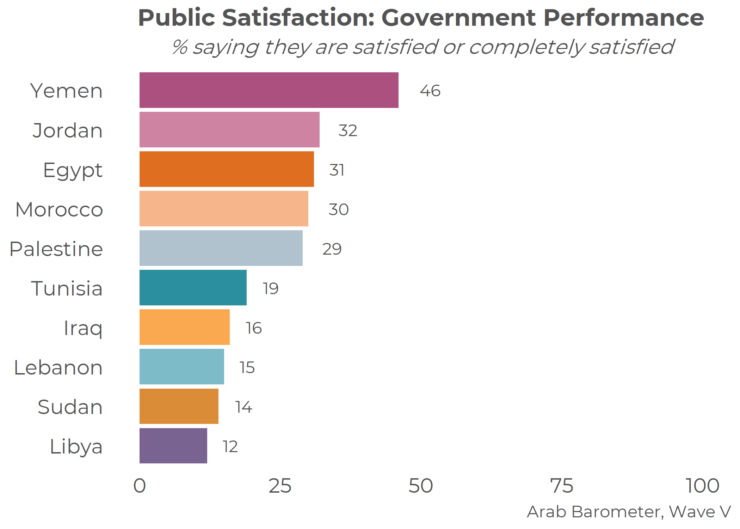

Unfortunately, as governments across the MENA region face the pandemic, public trust in healthcare services—as well as in government overall—is conspicuously low. Since the Arab Barometer began its surveys in 2006–2007, overall satisfaction with government performance has not exceeded 50 percent in any country. In the fifth wave of the survey, satisfaction with government services ranged from 12 percent in Libya to 46 percent in Yemen, showing a low degree of confidence in government. Low trust in government performance in general also extends to healthcare services in particular in the region. Only 37 percent of Arab Barometer respondents across all countries surveyed were satisfied or completely satisfied with the healthcare system in their country. Satisfaction ranged from a low of 18 percent of respondents in Libya to a high of 63 percent in Jordan.

Such low trust does not bode well for effective responses to COVID-19 in the region, and early government responses seemed to fulfill expectations of low transparency. For example, the Egyptian government revoked the press permit of a journalist who published research predicting high numbers of cases in the country and arrested citizens accused of spreading “rumors” about the virus. These measures did little to reassure Egyptians, and exacerbated public mistrust of both government institutions and the probable pandemic response.

Whether or not citizens in MENA trust medical institutions, their ability to access them will also determine the effectiveness of responses to COVID-19. Even outside of times of crisis, access is an impediment to healthcare for many citizens in the region. 47 percent of the respondents to the fifth wave Arab Barometer across all countries surveyed believed that paying a rashwa, or bribe, in order to access better healthcare services was highly necessary or necessary. Furthermore, the capacity of healthcare systems in many MENA countries is low. Compared to the world average of 2.7 hospital beds per 1,000 people, the Arab World is below average with 1.6 beds per 1,000 people; the number is as low as 0.7 beds per 1,000 people in Yemen. Additionally, World Health Organization data shows a worrisome lack of medical personnel in some MENA countries: Morocco, Egypt, and Iraq have 7.3, 7.9, and 8.2 physicians per 10,000 people, respectively, far lower than the WHO recommendation of 44.5 doctors per 10,000 people.

These numbers suggest that during the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems across the region may not have the capacity to treat the large numbers of patients requiring hospitalization. In Egypt, stories are already circulating of people desperately trying to find hospitals with space to treat their loved ones infected with COVID-19. Widespread corruption and belief that bribes are necessary to obtain satisfactory healthcare services cannot be comforting in this situation. Furthermore, doctors are not faring better than patients: medical personnel are threatening to resign en masse following the deaths of Egyptian doctors amid shortages of personal protective equipment.

For countries mired in conflict that has already weakened their institutions, COVID-19 threatens to decimate healthcare systems. Although Yemen leads its neighbors in terms of overall satisfaction with government services according to the latest Arab Barometer survey, Médecins Sans Frontiers reports that hospitals are shutting down due to the pandemic, and predict many preventable deaths as well as the complete collapse of the healthcare system. In Libya, MSF details a similar situation of medical facilities closing due to lack of staff and supplies.

With the COVID-19 crisis still ongoing, it is too early to fully judge the response of countries in the Middle East and North Africa to the pandemic. The lack of public trust in and capacity of healthcare systems across the region, however, indicates that COVID-19 may prove a formidable political as well as public health and economic challenge for many MENA countries.

Erin Hayes graduated from the University of Notre Dame with a degree in Political Science and Arabic and currently lives in Cairo, Egypt.