It is no secret that the Arab World has had a prolonged and sustained crisis in governance. This crisis was the primary driver behind the massive protest wave that swept through Arab countries beginning in 2011, leading to political instability and regime collapse, which is still reverberating today. Thus, the questions of trust in government and evaluation of governance are perennially relevant for Arab publics. Even in Tunisia, the most successful outcome of the 2011 protest wave, the crisis in governance is a work-in-progress yet to be resolved.

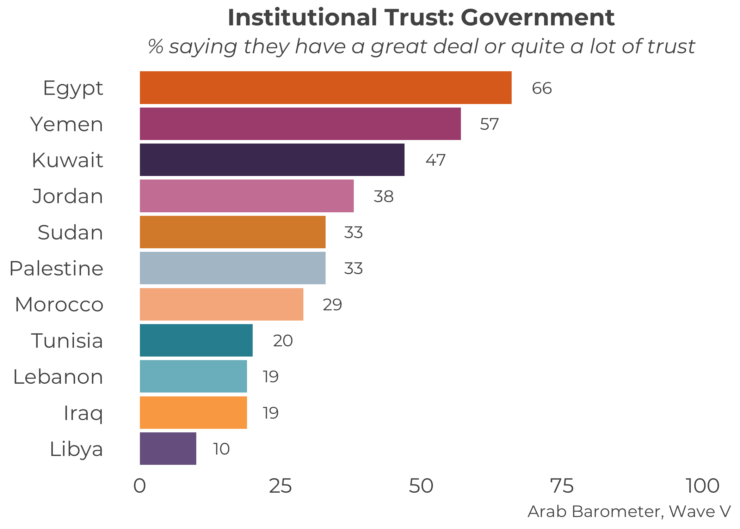

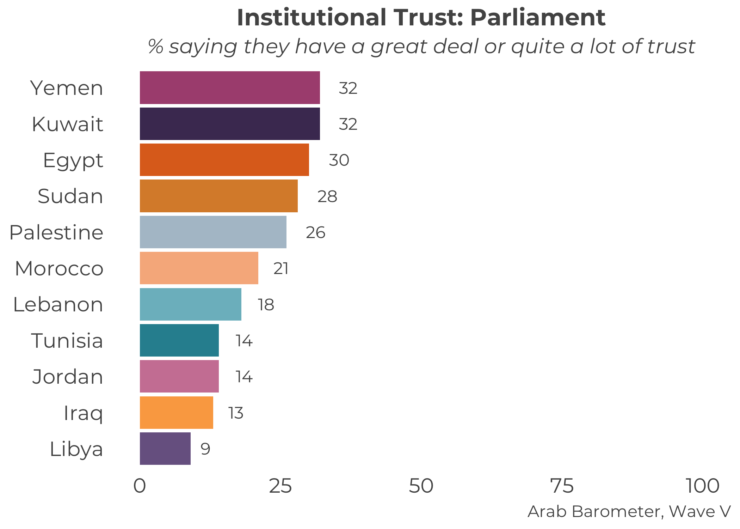

Previously, I have written in the Arab Pulse about levels of institutional trust in the Arab World. While levels of trust in government are generally low, they remain above other, ostensibly more representative political institutions (parliaments and political parties), and exhibit a large variance between different Arab governments. According to Arab Barometer Wave 5 data, trust in government varies tremendously, from 66 percent in Egypt, to 57 percent in Yemen, 47 percent in Kuwait, 38 percent in Jordan, 33 percent in Palestine and Sudan, 29 percent in Morocco, 20 percent in Tunisia, 19 percent in Iraq and Lebanon, and just 10 percent in Libya.

What do these figures mean? And how are they best interpreted? One way to interpret the data is that there is an inverse correlation between levels of freedom to criticize the government and trust in government. Namely, the higher the levels of freedoms to criticize the government, the less people trust the government. That is, the cost of outwardly expressing distrust of government is relatively low in countries where these figures are lowest (Libya, Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia). A second way to interpret the data is to measure it against historical benchmarks or compare it with the trend data available. According to previous waves of Arab Barometer data, trust in government actually increased in Lebanon and Yemen, remained stable in Egypt and Palestine, and declined in Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia. This seems to suggest that there is no regional trend, that national context is of paramount importance, and that generalizing across different countries is difficult.

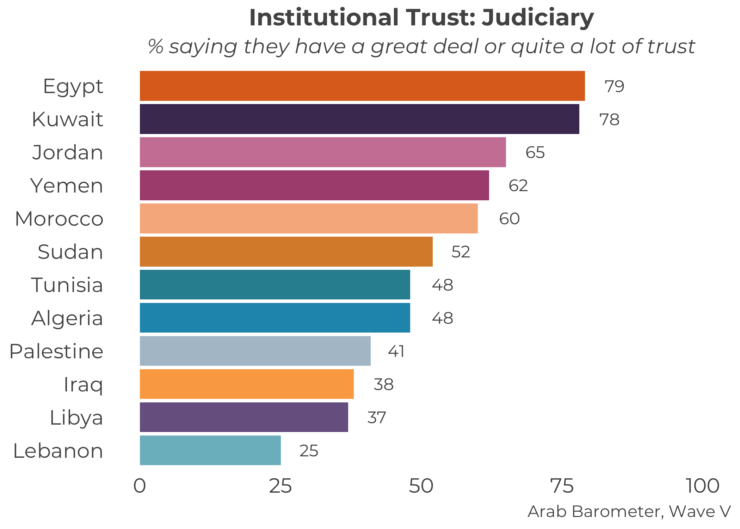

Here it is important to differentiate between different layers of governance that, though may seem interchangeable, need to be analytically disentangled. In teaching comparative political institutions, political scientists often differentiate between state, regime, government institutions on a hierarchical pyramid. At the very bottom, lies the state with its foundational sovereign institutions – the national army, the civil service, the security establishment, and the judiciary. Notably, these are the types of public institutions that typically enjoy higher levels of trust in Arab countries. Atop the state institutions, lies the regime – with its democratic or, more frequently in Arab countries authoritarian structures. This includes the quality and frequency by which there is leadership change in state institutions, including the government. The top of the pyramid features the government, executive branch or council of ministers that is in charge of managing the day-today affairs of the country.

The Arab Barometer battery of questions makes explicit that by asking about “The Government” it is asking about the council of ministers or executive branch. The remaining battery of questions identify other state institutions such as the army, the judiciary, parliament, and so on – including the head of government. That being said, authoritarian regimes deliberately blur the lines between government, regime and state institutions to threaten society with state collapse in the event of regime collapse. This grim scenario was avoided in Tunisia and Egypt after 2011, but took place in Iraq after 2003, and Libya and Yemen after 2011 – and while the regime has not (yet) collapsed in Syria, the state certainly did (to the extent that a ‘state’ existed in Assad’s Syria). Within such regimes the extent to which the council of ministers actually rules is always unclear (hint: it often doesn’t). This makes extrapolating from the trust figures even more perilous.

The Arab Barometer battery of questions makes explicit that by asking about “The Government” it is asking about the council of ministers or executive branch. The remaining battery of questions identify other state institutions such as the army, the judiciary, parliament, and so on – including the head of government. That being said, authoritarian regimes deliberately blur the lines between government, regime and state institutions to threaten society with state collapse in the event of regime collapse. This grim scenario was avoided in Tunisia and Egypt after 2011, but took place in Iraq after 2003, and Libya and Yemen after 2011 – and while the regime has not (yet) collapsed in Syria, the state certainly did (to the extent that a ‘state’ existed in Assad’s Syria). Within such regimes the extent to which the council of ministers actually rules is always unclear (hint: it often doesn’t). This makes extrapolating from the trust figures even more perilous.

Due to the historic quality of governance in Arab countries, Arab publics often instinctively distrust their governments. As a result, it rarely matters who occupies the executive branch of government – trust in the government as an institution will be low. Compared to other regime or state institutions (such as the army, security, or head of state), Arab publics often feel empowered to express this lack of trust with relative freedom.

Finally, COVID-19 has presented Arab governments with a new type of challenge, some of whom are handling it better than others. It remains to be seen what impact the COVID-19 response will have on trust in government. In countries like Jordan, the government has surely salvaged its public relations image with the quality of its response. Countries like Egypt have not fared as well. Hopefully and once available, data from the sixth wave of the Arab Barometer will shed further light on this matter. Until this data is available and beyond, comparing trust in governance across the Arab world will remain an exciting though challenging intellectual exercise.