One of the most puzzling facets of contemporary Arab politics is the low level of trust in institutionalized political agents. While the average Arab citizens’ levels of trust in the security apparatus, the military, and the judiciary are relatively high, trust in the government/cabinet and local governments decline, reaching their lowest levels with Islamist movements and parties, parliaments, and political parties.

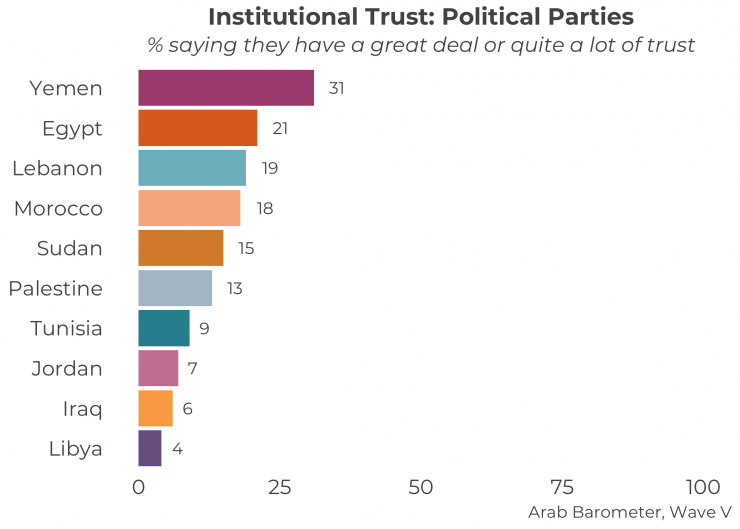

Data from the Arab Barometer’s fifth wave indicates very low levels of trust in political parties. With the exception of Yemen (31 percent), political parties obtain trust levels that range from 4-21 percent. In Egypt, those who exhibit some or great trust in political parties were 21 percent, in Lebanon they were 19 percent, in Morocco 18 percent, in Sudan 15 percent, and in Palestine 13 percent. The figure declines to below 10 percent in Tunisia (9 percent), Jordan (7 percent), Iraq (6 percent), and Libya (4 percent).

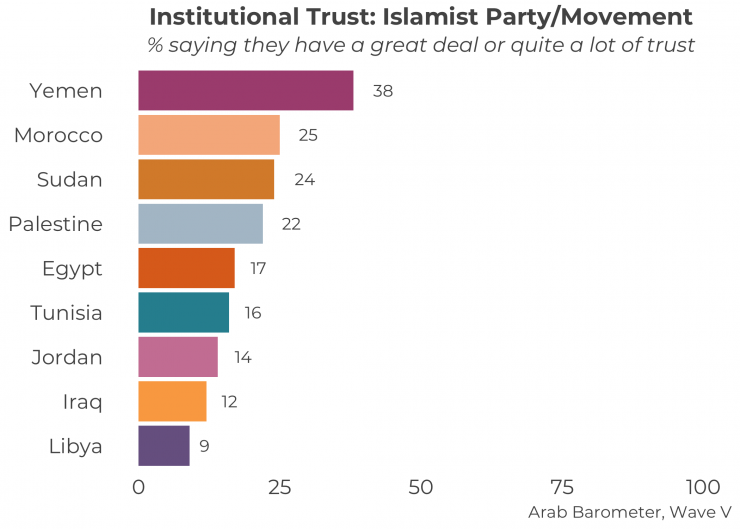

Islamist movements and parties do not fare much better even though they have higher levels of trust. Those who exhibit some or great trust in the main Islamist movement or party were 38 percent in Yemen, 25 percent in Morocco, 24 percent in Sudan, 22 percent in Palestine, 17 percent in Egypt, 16 percent in Tunisia, 14 percent in Jordan, 12 percent in Iraq, and 9 percent in Libya.

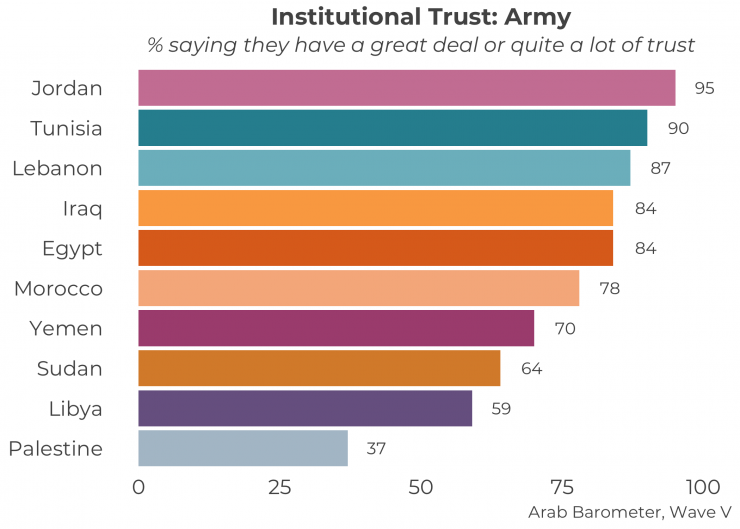

For those who follow Arab public affairs, these figures may not be surprising. Nevertheless, it is useful to contrast them with levels of trust in the military. Those who exhibit some or great trust in the army were 95 percent in Jordan, 90 percent in Tunisia, 87 percent in Lebanon, 84 percent in Egypt and Iraq, 78 percent in Morocco, 70 percent in Yemen, 64 percent in Sudan, 59 percent in Libya, and 37 percent in Palestine. With the exception of Palestine, these are the highest levels of trust in any of the institutions in which trust was measured.

What are possible explanations for diminished trust in parties, and their unpopularity in comparison with other security and political institutions? Of the many hypotheses put forward concerning this phenomenon, one is that Arab citizens feel freer to criticize political parties and parliaments and to blame them for political stagnation in Arab countries. Another is that security institutions have the organization, integrity and discipline that is lacking from most Arab political parties. Lastly, it could be argued that political parties do not control their own decision-making, are unable to influence political developments, and have just become ideological clubs, sitting on the sidelines hesitating to participate in the most basic mass protest movements – as most sat out the Arab Spring demonstrations.

The explanation that I privilege, based on my research on the Moroccan case, fuses the above hypotheses by adopting a historical perspective. Arab political parties are social intermediaries between regimes and publics. They participate in the political system, even if they do not participate in the regime (Tunisia, Lebanon and Iraq are exceptions). Of all Arab political structures, they are the easiest to reach and criticize freely in the public sphere.

In non-partisan authoritarian regimes (as in regimes that lack a leading party), which includes most Arab countries today, parties form and develop to formulate ideologies and social programs and influence public discourse, knowing well that they may not rule (Tunisia is the exception since 2011). In certain historical episodes, these parties have obtained significant organizational and mobilization capacities, withstood repression at the hands of the authorities, and paid a steep price for confronting authoritarian and repressive structures (indeed, some still do). Over time, regimes have been able to contain these parties either through incorporating them into the regime in a limited capacity (cooptation) or violently repressing them (coercion). The few parties that have been able to maintain their relevance over time are ones that took a critical distance from the regime, maintained their popular bases, adhered to their public discourse, and did not pursue momentary narrow gains.

Parties have absorbed some of the public pressure on the regimes for quite some time, which may explain the low trust figures observed above. The problem now, as Instissar Faqir argues, is that by eroding the roles of mediary institutions, Arab regimes have paved the way for open confrontations with their societies. This is what we observed in most Arab countries during the protest wave that started in 2011 and is still ongoing. Parties have found themselves on the losing end for both sides of the confrontation: neither have they obtained ruling authority, nor have they obtained the publics’ trust and respect.

Thus, parties face a dual challenge. The first is survival: continuity and coexistence with regimes that make no secret of their historical disdain of any institutionalized public political agency. The second, which I think is more difficult to overcome, is to justify this continuity and convince Arab societies of the value of sustained institutionalized political agency. This is a difficult challenge, one that may exceed the capabilities of Arab political parties. But recent history teaches us that the cost of political party activism may be justified, especially if parties can help evade the most violent aspects of the open confrontations between regimes and societies. Otherwise, Arab societies will fall prey to their security establishments, the trust in which they may have misplaced.