According to the narrative echoed among journalists, analysts, and academics, the frustrated unemployed were an important driving force behind the so-called Arab Spring uprisings. Based on my recent research article , the role of unemployment behind the Arab Spring, however, does not seem that crucial.

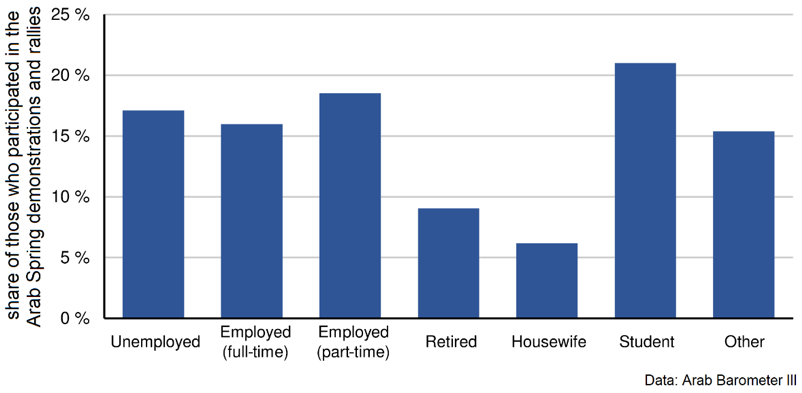

The graph above shows the share of those who participated in the Arab Spring protests by employment status. The data of the graph is drawn from the third wave of the Arab Barometer, where respondents are asked whether they in 2011 and 2012 had participated in demonstrations and rallies to which the Arab Spring led. The data covers twelve Arab countries.

The results from the graph make clear that employment status is linked to the likelihood of protest participation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, students were most active in the Arab Spring uprisings while those who are retired and housewives the most passive. However, the difference between those who are employed versus unemployed appears marginal.

When more sophisticated statistical analyses are used the result is similar; there is hardly difference between rates of participation in the protest by the unemployed compared with those who are employed. In some countries and in some other subsamples, the unemployed were even less active in taking to streets than the employed. The outcome is the same when using the third wave of the Arab Barometer data and when analysing the data of the Arab countries of the sixth wave of the World Values Survey. In the World Values Survey, respondents are asked whether they have participated in peaceful demonstration. In the article, I analysed some 25,000 respondents from these two surveys.

The unemployed have been dissatisfied but not politically active

However, the results also show that those who are unemployed across Arab countries are less satisfied with their lives than their employed compatriots. Overall, those who are unemployed have not been particularly interested in politics. Nevertheless, being dissatisfied with one’s life does not influence the likelihood that an individual takes to the streets, but those who are interested in politics are considerably more active protesters. Taken together, the results indicate that the Arab unemployed were unhappy, but most likely this dissatisfaction did not erupt as participation in the uprisings due to their low interest in politics.

The idea that frustrated unemployed riot might seem straightforward first. But on the other hand, a person who is unemployed is likely to face greater difficulties in feeding his or her self or family. Thus, concerns about the country’s political system may take a backseat to more basic considerations. In addition, the unemployed are generally economically less secure and have relatively smaller social networks, which are likely to hamper participation in political protests.

In addition to the Arab Spring, unemployment is thought to increase likelihood for rebellions, terrorism, armed conflicts, and political violence in general. The above presented outcomes together with some earlier results from different corners of the world suggest that the linkage of unemployment and political instability may be remarkably weaker than often assumed. Thus, programmes aiming at fostering social stability solely through creating jobs may be mistargeted.

– – – –

The blogpost is abridged and adapted version of the article ‘Are the unhappy unemployed to blame for unrest? Scrutinising participation in the Arab Spring uprisings’ published under CC BY 4.0 in Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy

Kari Paasonen is the Acting Executive Director of the peace and security think tank SaferGlobe and Doctoral Researcher at the Tampere Peace Research Institute (TAPRI), Tampere University.